Nature uses 20 accepted amino acids as building blocks to make proteins, joining their groupings to make complex atoms that carry out organic roles.

But what happens when the groupings are not chosen randomly?Also, what are the prospects for creating completely new groupings to create novel (new) proteins that resemble anything in nature?

That is the territory where Michael Hecht, a teacher of science, works with his examination bunch. As of late, their interest in planning their own groupings has paid off.

They found the main known new (recently made) protein that catalyzes (drives) the union of quantum dots. Quantum dabs are fluorescent nanocrystals utilized in electronic applications, from Drove screens to sun-powered chargers.

Their work paves the way for making nanomaterials in a more feasible manner by showing that protein groupings not obtained from nature can be utilized to blend useful materials—wwith articulated advantages to the climate.

Quantum dabs are typically made in modern settings with high temperatures and harmful, costly solvents—aa cycle that is neither prudent nor harmless to the ecosystem. Yet, Hecht and his examination bunch pulled off the cycle in the lab involving water as a dissolvable, making a steady final result at room temperature.

“We’re keen on making life atoms and proteins that didn’t emerge throughout everyday life,” said Hecht, who drove the examination with Greg Scholes, the William S. Tod Teacher of Science and seat of the division. “Here and there, we’re wondering if there are alternatives to life as far as we’re concerned.”A normal family gave birth to all life on Earth.But, if we create exact atoms that don’t come from normal families, will they ever be able to do cool things?So we’re creating novel proteins that have never been seen before by doing things that don’t exist in nature.

The group’s cycle can likewise tune nanoparticle size, which determines the variety where quantum dabs shine or fluoresce. That holds opportunities for labeling particles inside a natural framework, such as staining disease cells in vivo.

“I believe that employing de novo proteins allows for designability.” ‘Engineering’ is an important word for me. I want to be able to build proteins to accomplish specific things, and this is a type of protein that allows you to do so.”

Leah Spangler, lead author on the research and a former postdoc in the Scholes Lab.

“Quantum dabs have extremely fascinating optical properties because of their sizes,” said Yueyu Yao, co-creator of the paper and a fifth-year graduate undergrad in Hecht’s lab. “They’re truly adept at retaining light and changing it over completely to compound energy—that makes them helpful for being made into solar-powered chargers or any kind of photosensor.”

“Yet, then again, they’re likewise truly adept at radiating light at a specific desired frequency, which makes them reasonable for making Drove screens.”

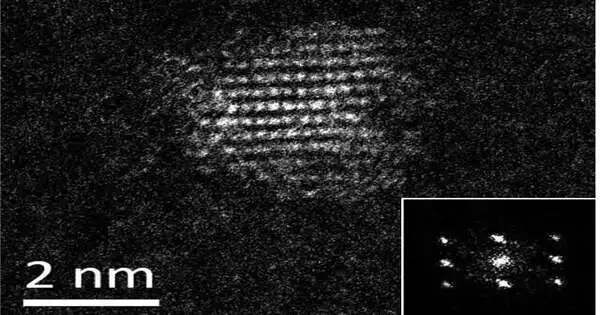

Also, on the grounds that they’re little—mmade out of around 100 iotas and perhaps 2 nanometers across—they’re ready to enter a few organic hindrances, making their utility in medicines and natural imaging particularly encouraging.

Why use new proteins?

“I think utilizing new proteins opens up a way for designability,” said Leah Spangler, the lead creator on the examination and a previous postdoc in the Scholes Lab. “A watchword for me is ‘design.'” I need to have the option of designing proteins to accomplish something explicit, and this is the sort of protein you can do that with.

“The quantum dab we’re making isn’t incredible quality yet, but that can be improved by tuning the blend,” she added. “We can accomplish better quality by designing the protein to impact quantum dot development in various ways.”

Based on the work of related creator Sarangan Chari, a senior scientist in Hecht’s lab, the group used a new protein called ConK to catalyze the reaction.Scientists originally decoupled ConK in 2016 from a huge combinatorial library of proteins. It’s actually made of normal amino acids, yet it qualifies as “once more” on the grounds that its grouping has no likeness to a characteristic protein.

Analysts discovered that ConK improved E. coli endurance in potentially harmful copper concentrations, implying that it could be useful for metal restriction and sequestration.The quantum dots utilized in this examination are made from cadmium sulfide. Cadmium is a metal, so scientists contemplated whether ConK could be utilized to blend quantum dabs.

Their hunch paid off. ConK separates cysteine, one of the 20 amino acids, into a few items, including hydrogen sulfide. That serves as the dynamic sulfur source, which will then respond with the metal cadmium.The outcome is CDS quantum dot analysis.

“To make a cadmium sulfide quantum dot, you want the cadmium source and the sulfur source to respond in agreement,” said Spangler. “What the protein does is gradually create the sulfur source over time.”Thus, we add the cadmium at first, but the protein creates the sulfur, which then responds to make particular sizes of quantum dots.

The review is distributed in the diary, Procedures of the Public Foundation of Sciences.

More information: Leah C. Spangler et al, A de novo protein catalyzes the synthesis of semiconductor quantum dots, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2204050119. www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2204050119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences