We stand in the open fields of Spanish Post, a modernized Mennonite-cultivated local area in Focal Belize, seeing what remains of tribal Maya homes. As may be obvious, white hills, the leftovers of these houses, scar the scene, as may be a distinct sign of what existed over a long time ago. The fallen structures seem to be smeared on a flying photo, yet as archeologists, we get to see them very close. With enough removal and translation, we can ultimately figure out how these homes worked in the profound human past.

Archeologists normally attempt to take a delegate test of a site like this, yet we are restricted on how and where we can exhume. We have been compelled to choose families and different designs close to existing streets—and near each other. This, then, presents a novel opportunity: the capacity to concentrate on a tribal Maya area.

Our local paints an intriguing picture of existence with regards to the Early Exemplary period, which dates from A.D. 250–600. By taking a gander at the styles, structures, and designs of broken bits of ceramic, called sherds, we can decide how old these designs are. Standard homes have walls, mortar floors, and an assortment of homegrown vessels that are utilized for cooking, serving, and stockpiling. We also find rural tools made of chert, a glasslike rock that looks like stone, as well as manos and metates, which were used to grind maize into flour.

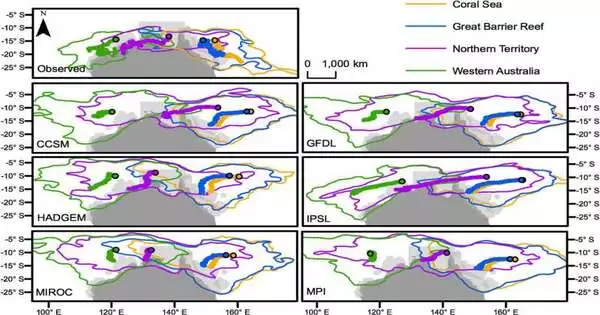

“It can take decades to millennia for coral communities to recover from the damage caused by catastrophic weather events—and conservationists must direct their limited efforts toward reefs that are more likely to endure climate change.”

Dr. Marji Puotinen, a spatial and ecological data scientist

Families lived and worked here, connected with their neighbors and with the encompassing scene of fields and woods. We realize the Maya left woods set up on the grounds that the creature bones we find here are of species that can be raised in the woodland.

flying photo of what scientists accept is a local area structure, similar to a congregation or diversion focus. VOPA and Belize Foundation of Paleontology, NICH.

One of the structures here is a specific riddle. The tribal Maya built it utilizing uniform stones and white limestone mortar, something else from your typical Maya farmstead. We found not many curios and perfect development fills, the last option normally loaded with relics in a common Maya family. We assume we discovered some sort of local area building, maybe for local area occasions or services, like a cutting edge church or diversion focus, where everybody was gladly received.

We also somewhat uncovered a significant stage hill that had four designs at its culmination. The designs encompassed a square or yard. Obviously a top-notch family lived here. This hill would have been confined, divided from the remainder of the area, similar to the huge house toward the end of a parkway where, in the event that you were fortunate, you were welcomed for a pool party, very different from the local area buildings.

Both the tip-top and nonelite families that lived in this area together may have put resources into the development of the local area, working in the midst of the encompassing homes. The relics recuperated from the public venue were of preferred quality over those tracked down in homes. We even found a store of 15 stemmed focuses made of chert. These things required incredible ability to make as they were cut from the best non-local chert. What’s more, the Maya made them just to offer them unused as a dedicatory store to charge up or bless the home with a spirit.

As we check out, we are struck by the basic truth that individuals lived here.

When we ponder the designs and relics related to neighborhoods and public venues, we time and again reduce the tribal Maya to the materials they abandoned. We sometimes center a lot around the setting name, the hill number, or the curio count. As we stand at the junction of an old Maya area, in the event that we shut our eyes and let the current disappear, we can envision the everyday real factors of life in this precise spot almost a long time ago: the stir of the leaves of the wilderness above us, the scratch and clunk of crushing maize, the smell of cooking maize and beans, or the gab of a neighbor getting a device or getting some information about the climate.

We are put down by the harm created by current farming to the archeological record and Maya social legacy. Yet, how would you clarify to a rancher that what they are furrowing away isn’t an irritation stone or futile piece of ceramics, but rather the parts of many lives? The phantoms of the people who resided on the land before us stroll between us, utilizing what survives from their homes to murmur, “Recall me.”

More information: Adele M. Dixon et al, Coral Reef Exposure to Damaging Tropical Cyclone Waves in a Warming Climate, Earth’s Future (2022). DOI: 10.1029/2021EF002600

Journal information: Earth’s Future