Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine say they discovered that a protein that helps construct a structural network beneath the surface of the cell’s “command center” its nucleus is critical for keeping DNA inside it organized in a lab-grown mouse cell study.

The new research clarifies the function of a protein known as lamin C, demonstrating its utility in diagnosing and treating a variety of hereditary illnesses associated to DNA disarray, including progeria, muscular dystrophy, and cardiac ailments caused by mutations in these and related proteins.

“Because lamin C appears to be critical for genome organization in general, the implications of our discoveries potentially go beyond the recognized laminopathic illnesses. We simply don’t know how lamin C behaves in other disorders characterized by genome dysregulation at this time “Karen Reddy, Ph.D., assistant professor of biological chemistry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, agrees.

She says, “Many people are aware that gene mutations, or flaws in the genetic code, cause inherited diseases. However, disordered genes may be just as effective as mutations in producing disease.”

Reddy observes that most genetic tests do not take into account the mechanics of how DNA is organized, which may be a crucial foundation for understanding hereditary illnesses. Reddy and her colleagues published the findings of their investigation in Genome Biology.

Many people are aware that gene mutations, or flaws in the genetic code, cause inherited diseases. However, disordered genes may be just as effective as mutations in producing disease.

Karen Reddy

The nucleus of each human cell contains around 6 feet of tightly coiled DNA that contains the genetic instructions for every structure and function in the body. These DNA threads must be arranged into usable portions in order for the cell to function. The lamin proteins, which connect to the surface of the nucleus, accomplish this by grasping onto DNA segments and maintaining them distinct and orderly.

“Each compartment created by a lamin operates like a kitchen tool drawer, keeping knives, forks, and spoons easily accessible and more rarely used objects like serving pieces out of the way until needed,” Reddy explains.

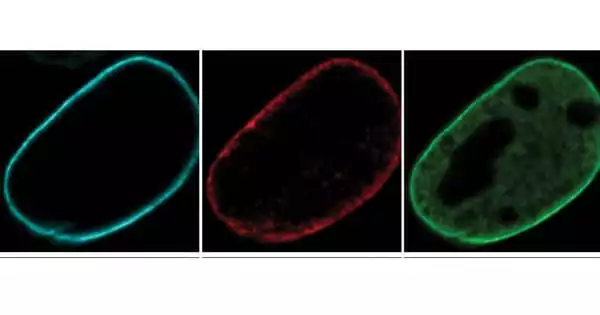

Reddy and her colleagues employed fluorescent dyes to track three types of lamin proteins – A, B, and C – through cell division, when DNA from one cell is duplicated and shared between two daughter cells, in order to better understand how lamins influence how the cell uses and organizes its DNA.

While lamin B has been easily distinguished in earlier research, lamin A and C have traditionally been classified as duplicate proteins because they are produced by the same gene, according to Reddy. However, there was mounting evidence that A and C type lamins served separate functions.

To distinguish between them, Reddy’s team genetically modified mouse embryonic cells to eliminate either the gene that produces lamin B or the gene that contains both lamins A and C. The researchers next used microscopes to observe how the lamins behaved and if the nuclear DNA of the cells remained ordered as it divided.

The researchers discovered that nuclear DNA in cells lacking lamin B appeared almost identical to normal dividing cells, hinting that lamin B may not be required for DNA reorganization following cell division. Nuclear DNA in cells lacking lamins A and C, on the other hand, did not reorganize neatly, becoming twisted and disorganized from its typical compartments within the nucleus.

“It looked like a noisy party was going on in the generally well-organized kitchen,” Reddy says of the cells without lamins A and C. “Things were not in their proper placements, and the strands of active and inactive DNA were mixed together and separated from the lamins at the nucleus’s periphery.”

The researchers next utilized a series of specialized chemical reagents to disable either lamin A or lamin C in mouse cells, allowing them to examine each protein separately. Cells lacking lamin A appeared to be able to rearrange following cell division just as well as normal cells. However, in cells lacking lamin C, nuclear DNA structure became disorganized once more.

According to Reddy, the action of lamin C in dividing cells indicated the cause for this divergence. While lamins A and B instantly connect to the surface of a freshly formed nucleus and begin grabbing pieces of DNA, lamin C remains scattered throughout the nucleus and retains a particular chemical tag known as phosphorylation. The researchers believe that this mutated lamin C aids in the placement of DNA during reorganization. Once the DNA is structured, lamin C loses its molecular tag and joins the rest of the lamins at the nucleus’s edge.

“There is this wonderful choreography of the multiple lamin proteins and DNA to get things just right,” Reddy explains. The findings suggest that new tests that discriminate between lamins A and C could be developed and should be considered when screening for some hereditary illnesses that involve lamin proteins or other proteins near the nucleus’s border.

The gene that codes for lamins A and C is linked to three types of muscular dystrophy: familial partial lipodystrophy, a syndrome that causes aberrant fatty tissue distribution; progeria; and various heart muscle abnormalities.

The findings raise several new questions, according to the researchers, including the role of lamins in organizing and regulating DNA during development. Because there appears to be some cross-talk between the many types of lamins, the research aims to uncover how lamin proteins and the genome react when one specific kind of lamin is mutated or disrupted. They also intend to explore the biological mechanisms that govern the lamin proteins, notably lamin C, in order to better understand the significance of its involvement in DNA regulation.