Northwestern Medicine researchers are leveraging recent developments in CRISPR gene-editing technology to discover novel biology that could lead to longer-lasting treatments and new therapeutic tactics for Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV). The HIV epidemic went unnoticed during the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is a serious and continuous threat to human health, with an estimated 1.5 million new infections in the last year alone.

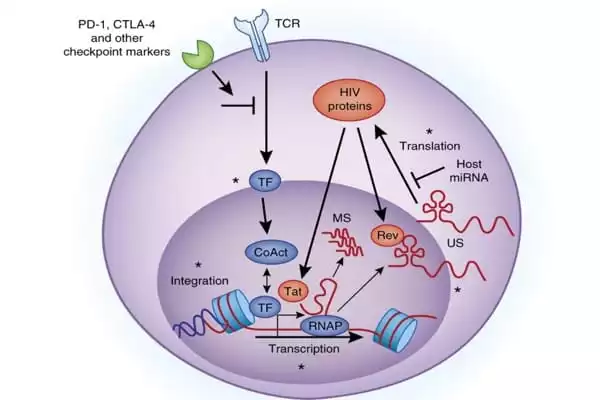

For more than 40 years, drug makers and research teams have been looking for cures and new treatment regimens for HIV, but they have been constrained by their understanding of how the virus establishes infection in the human body. How does a virus with only 12 proteins and a genome a third the size of SARS-CoV-2 hijack the body’s cells to replicate and move across systems?

A multidisciplinary team at Northwestern attempted to answer this question. The team’s new study, published in the journal Nature Communications, used a new CRISPR gene-editing approach to identify human genes that were important for HIV infection in the blood, finding 86 genes that may play a role in the way HIV replicates and causes disease, including over 40 that had never been looked at in the context of HIV infection.

The present medication therapies are one of our most significant instruments in addressing the HIV epidemic and have proved extraordinarily effective at suppressing viral replication and dissemination.

Judd Hultquist

The work presents a new map for understanding how HIV integrates into human DNA and forms a chronic infection.

“The present medication therapies are one of our most significant instruments in addressing the HIV epidemic and have proved extraordinarily effective at suppressing viral replication and dissemination,” said co-corresponding author Judd Hultquist of Northwestern University. “However, because these medications aren’t curative, those living with HIV must adhere to a stringent treatment regimen that necessitates constant access to decent, inexpensive health care — which is just not the society we live in.”

Hultquist believes that with a better understanding of how the virus multiplies, treatments could one day lead to cures. Hultquist is an assistant professor of medicine in infectious diseases at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the associate director of the Center for Pathogen Genomics and Microbial Evolution.

A method without compromise

Until far, researchers have relied on immortalized human cancer cells (such as HeLa cells) as models to examine how HIV replicates in the lab. While these cells are simple to control in the lab, they are inaccurate representations of human blood cells. Furthermore, unlike CRISPR, most of these research employ technology to reduce the expression of specific genes rather than completely turn them off, which means scientists can’t always tell if a gene was engaged in assisting or suppressing viral replication.

“There is no middleman with the CRISPR technology; the gene is on or off,” Hultquist explained. “The capacity to turn genes on and off in cells isolated directly from human blood is a game changer; this new assay is the most faithful picture of what’s going on in the body during HIV infection that we could easily investigate in the lab.”

T cells, the primary cell type targeted by HIV, were extracted from donated human blood and hundreds of genes were knocked out using CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. After that, the “knock-out” cells were infected with HIV and evaluated. Cells that lost a viral replication gene had a lower infection rate, but cells that lost an antiviral component had a higher infection rate.

The scientists next confirmed the revealed components by selectively knocking them off in new donors, where they discovered a roughly even split between newly discovered and well-researched pathways.

Moving toward a cure for HIV

Hultquist stated that their findings showed a “perfect split” of novel and known components, indicating that they were on the correct track.

“This is a really wonderful proof-of-concept that the methods and processes we used to conduct the study were solid and well thought out,” Hultquist said. “The fact that approximately half of the genes we uncovered have previously been discovered adds to our confidence in our dataset. The fascinating element is that more than half of these genes – 46 – had never been studied in the context of HIV infection, so they provide new prospective therapeutic paths to investigate.”

The team is eager to advance this technology to enable genome-wide screening, in which they will individually knock off or turn on every gene in the human genome to find all potential HIV host factors. These data would be an important component of the puzzle, bringing them even closer to curative strategies.

Hultquist at Northwestern University collaborated with Alexander Marson and Nevan Krogan at the University of California, San Francisco on the study.