The remarkable success of the federal government’s signature environmental laws is absent from partisan political debates regarding regulations affecting the energy sector. A good example is the U.S. Ecological Security Organization’s principles, which pointed toward lessening the hurtful impacts of risky air poison (HAP) emanations from petroleum-terminated power plants known as the Mercury and Air Toxics Guidelines, or MATS.

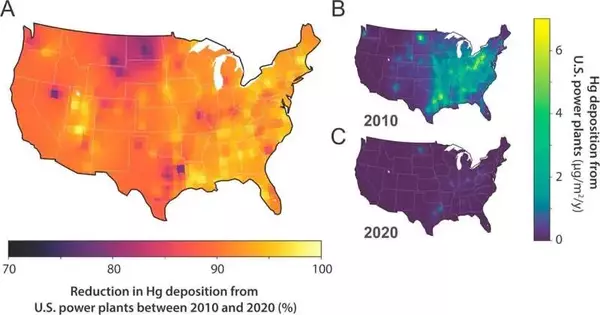

According to a new study from the Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences (SEAS), the amount of mercury released into the atmosphere from U.S. power plants—and eventually into the ground, water, and food web—decreased by 90% in the decade following the standard’s adoption. Mercury is a powerful neurotoxin, and exposure has also been linked to an increased risk of adult-caused heart attacks that result in death.

The new paper breaks down sociodemographic variations in mercury openings from U.S. power plants and leftover dangers for the most exceptionally uncovered populations. The study has been accepted for publication in Environmental Science & Technology Letters.

“This regulation effectively eliminated the majority of the last remaining point sources of mercury emissions in the United States, benefiting millions of freshwater and recreational anglers across the country.”

Elsie Sunderland, Fred Kavli Professor of Environmental Chemistry.

Prior to the implementation of MATS in 2011, coal-fired power plants accounted for the majority of the nation’s hazardous mercury emissions. In 2005, coal-fired power plants were the primary source of 50% of all mercury emissions in the United States. The MATS guideline constrained all power plant administrators to meet the top-level outflow control execution principles across the nation. Numerous administrators decided to close down coal-terminated power-producing units when the cost of petroleum gas fell. Some people have completely switched to natural gas as their fuel, which emits very little mercury. Of the 507 coal-terminated power establishments that were working in 2010 before the MATS rules came full circle, 230 were completely resigned and 62 were to some degree resigned by 2020.

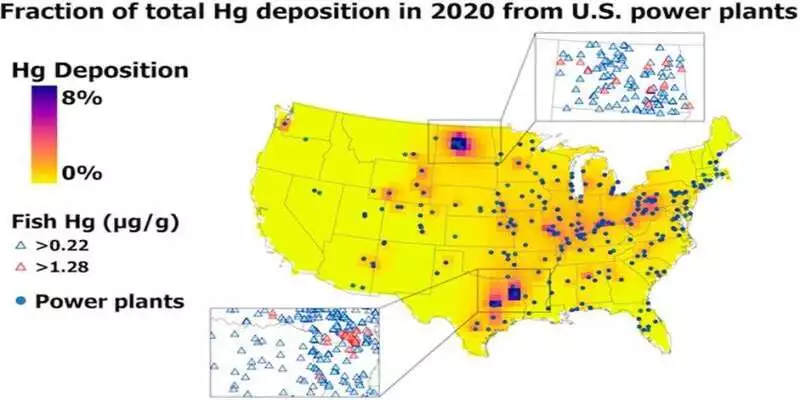

Texas and North Dakota remain focal points for mercury discharges from power plants. Credit: Harvard SEAS.

Elsie Sunderland, Fred Kavli Professor of Environmental Chemistry and Professor of Earth and Planetary Sciences at SEAS, said , “The MATS regulation is another wonderful success story linked to the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990. This guideline has really wiped out the vast majority of the final U.S. mercury emission point sources, with benefits for a huge number of freshwater and sporting fishermen the nation over.”

In spite of the historic progress that the nation has made, two regions stand out as persistent sources of mercury emissions: Texas and North Dakota. Power plants in both states use bituminous coal, which is used in most other parts of the country, instead of locally mined lignite coal, which is of lower quality and lower density. This implies that lignite consumption control guidelines for mercury in 2012 were less rigid than those produced for most U.S. power plants, and mercury discharges stayed higher in different regions after the MATS rule was carried out.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is obligated to check on a regular basis to see if there have been any significant advancements in technology that call for adjustments to the standards it The agency has now made changes to MATS that would force operators of lignite coal-burning power plants to use technologies that would significantly cut the amount of toxic gas they produce. These proposed more severe norms are open for public comment until June 23, 2023.

“Our most recent research suggests that the Biden Administration’s proposal to strengthen the MATS rule would eliminate the last two mercury deposition hotspots in the United States that are caused by coal-fired power plants. This is a significant change that will help weak networks and native gatherings,” said Sunderland.

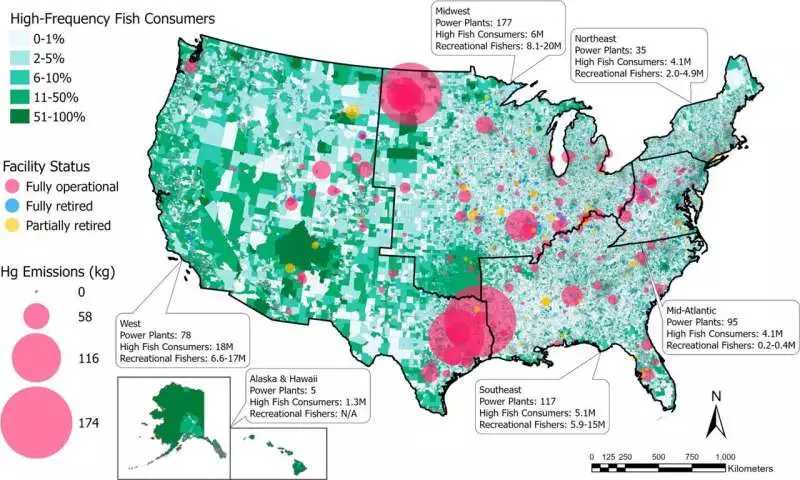

Mercury’s negative effects on health are most likely to affect those who consume fish from areas close to coal-fired power plants. Credit: Harvard SEAS

The Harvard team also looked into whether people who lived near power plants that would continue to operate in 2020 had different sociodemographic characteristics than people who lived near facilities that had retired since 2010. They discovered that low-income, less-educated, and English-speaking households are more likely to continue being exposed to hazardous mercury levels from power plant emissions.

Mona Dai, a Ph.D. student in Sunderland’s Lab and the first author of the new paper, stated, “This work reinforces the lack of distributional justice in the siting of U.S. pollution sources and exposures, with effects on the health of the most vulnerable individuals and communities.”

Benjamin Geyman and Colin Thackray from SEAS, as well as Xindi Hu from Mathematica, Inc., are additional authors.

More information: Mona Q. Dai et al, Sociodemographic Disparities in Mercury Exposure from United States Coal-Fired Power Plants, Environmental Science & Technology Letters (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.3c00216