Assuming that specialists in medical clinic crisis divisions are prepared to do ultrasound on patients with profound vein apoplexy (DVT), they can almost divide the time the patients spend in these areas.

Dr. Ossi Hannula, a crisis medication expert at the Prosperity Administration’s Province of Focal Finland, Jyväskylä, Finland, who introduced the discoveries at the European Crisis Medication Congress, said his discoveries could assist with lessening stuffing in crisis divisions and further develop passing rates by empowering patients at the most serious risk of biting the dust, normally from non-DVT-related issues, to be dealt with all the more rapidly by crisis staff.

“Drawn-out stays in crisis offices are connected to crisis division swarming,” he said. “The longer a patient stays in a crisis division, the higher the passing rates and the dangers of different complexities; the more drawn out their visit in a clinic ward, the lower the patient fulfillment; and the higher the monetary expenses and the weight on crisis office staff.”

“Prolonged stays in emergency rooms are associated with emergency room crowding. The longer a patient spends in an emergency department, the greater the chance of death and other problems, the longer their stay in a hospital ward, the worse patient satisfaction, and the greater the financial costs and load on emergency department staff.”

Dr. Ossi Hannula, an emergency medicine specialist at the Well-being Services County of Central Finland, Jyväskylä, Finland,

DVT is blood coagulation in a vein, ordinarily in the leg, and it is a typical condition in patients showing up in crisis divisions, representing 1–2% of every single such visit. An ultrasound check, generally performed by radiographers or radiologists in the emergency clinic’s imaging division, is the typical method for diagnosing it, and medicines incorporate anticoagulant drugs (or “blood thinners”) to stop the coagulation from developing and to forestall it from severing and going in the circulation system to different pieces of the body, like the lungs. Assuming this occurs, it tends to be lethal.

Dr. Hannula’s prior examinations had shown that assuming general experts working in essential consideration were educated to perform ultrasound filters on patients with suspected DVT, they alluded fewer patients to clinic crisis divisions, bringing about less swarming and lower costs. He chose to check whether ultrasound performed by crisis doctors rather than radiographers and radiologists could diminish the time patients spent in crisis divisions.

Between October 2017 and October 2019, 93 patients with suspected DVT were enrolled in the forthcoming review in two medical clinics: Tampere College Medical Clinic and Kuopio College Emergency Clinic. They were remembered for the review in the event that a crisis specialist who had been prepared to perform ultrasound checks analyzed them and played out the vital ultrasound themselves.

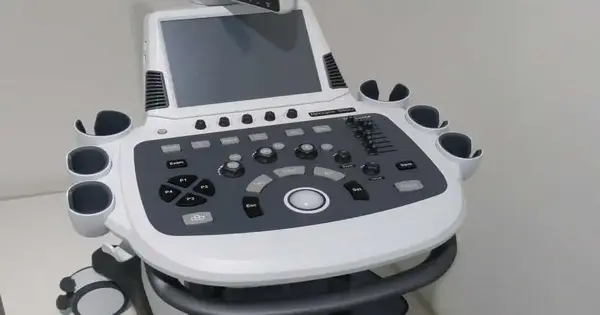

This is designated “mark-of-care ultrasound” (POCUS). POCUS should be possible at the bedside in the crisis division, in the clinic ward, in an emergency vehicle, or in a cataclysmic event. On the off chance that the specialist figured a patient ought to likewise be alluded to the imaging division, they could do this as well as perform POCUS themselves. The patients were mature (nearly 18 years old) and ready to give informed consent in Finnish.

“The point of point-of-care ultrasound is to respond to explicit inquiries, for example, ‘Is there a profound venous apoplexy that makes this leg expand?’ or ‘Are there gallbladder stones present causing the stomach torment?'” said Dr. Hannula.

Eleven crisis medication-trained professionals and junior specialists in the two clinics analyzed the patients in the review. Subsequently, Dr. Hannula contrasted the outcomes with a benchmark group of 135 patients who showed up in similar crisis divisions with suspected DVT on those very days yet were sent for ultrasound filters in the clinics’ imaging offices.

“We found that patients going through the standard ultrasound assessment spent a normal of 4.51 hours in the crisis divisions, while those getting point-of-care ultrasound spent a normal of 2.34 hours in the crisis offices—a distinction of 2.16 hours,” said Dr. Hannula.

“There have been blended outcomes from past investigations of point-of-care ultrasound that explored what it meant for the length of stay in crisis divisions. It appears that the outcomes can depend on the setting of the review. As this study was done in two different crisis divisions in the scholastic clinic, the outcomes are persuasive.

“The jamming in crisis offices is a rising danger to patient security as well as staff prosperity. Utilizing point-of-care ultrasound is one approach to handling this danger by lessening a superfluous postponement in direction.”

Dr. Hannula presently plans to check whether a comparable decrease in length of stay in crisis divisions can be accomplished in different examinations, for example, for gallstones.

Teacher Youri Yordanov from the St. Antoine Clinic Crisis Division (APHP Paris), France, is the seat of the EUSEM 2023 conceptual board and was not associated with the examination.

He said, “This study shows that mark-of-care ultrasound can give quick and exact determinations to patients who come to crisis divisions with thought-provoking vein apoplexy. A drive like this that can lessen the time that patients need to stand by in crisis divisions is exceptionally welcome, particularly as it can possibly diminish the tension on staff and work on the patients’ insight.”

Provided by European Society for Emergency Medicine