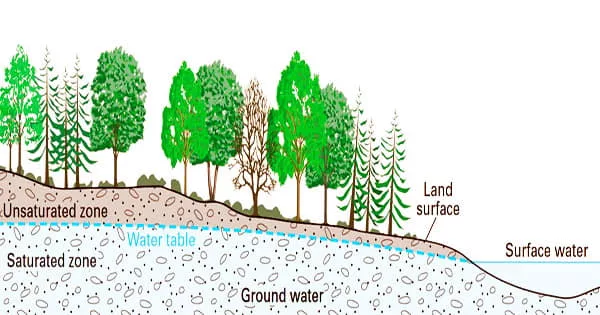

Along with storms and wildfires, another significant but little-discussed aspect of climate change is poisonous water and sinking soil, which is exacerbated by groundwater shortages. Snow and rainwater penetrate down into the earth between layers of soil and collect in aquifers, which are sponge-like underground bathtubs. Groundwater meets many of the hydrologic requirements of people all over the world where surface water, such as lakes and rivers, is sparse or unavailable.

When surface water supplies are insufficient, farmers rely largely on this groundwater to irrigate their crops. Pumping water out of the earth quicker than it is recharged causes comparable issues in the long run. Around 85% of Californians rely on groundwater for at least some of their water supply. It is believed that two billion people throughout the world rely on it.

In most physiographic and climatic contexts, groundwater contributes to streams. The amount of stream water that originates from groundwater input varies depending on the topography, geology, and climate of a given place. Excessive groundwater consumption, along with droughts, has caused the land surface to sink, causing key infrastructure such as roads, buildings, and sewage and water pipelines to be damaged.

If people pump groundwater without first letting it recharge, groundwater levels keep going down, the cost of pumping goes up, and the land sinks

Hoori Ajami

Groundwater, according to a new UC Riverside study, takes an average of three years to recover from drought, if it ever recovers at all. Scientists discovered in the largest research of its type that this recovery period only applies to aquifers that aren’t impacted by human activity, and that the recovery time might be significantly longer in areas where pumping is severe.

New precipitation must penetrate through the soil and replenish the depleted aquifer before groundwater levels may recover after a drought. The researchers discovered that in locations with deeper groundwater levels, this process might take many years longer.

“If people pump groundwater without first letting it recharge, groundwater levels keep going down, the cost of pumping goes up, and the land sinks,” explained Hoori Ajami, UCR groundwater hydrologist and study co-author and principal investigator on this project.

The new study, which was published in the Journal of Hydrology, is the first to look at groundwater response to droughts on a continental scale. Previous groundwater drought studies focused mostly on model simulations and covered smaller regions. This research was based on daily observations from 600 wells around the country for 30 years.

Rainwater drought takes around two years on average to turn into groundwater drought, however, it can take up to 15 years in certain circumstances, according to the study. The benefits aren’t felt or noticed right away due to the considerable lag period.

They can, however, be severe. Subsidence is a slow, uneven lowering of the land surface caused by groundwater shortage mixed with pumping.

“It is a known problem in California’s Central Valley, exacerbated by climate factors and excessive water pumping,” Ajami said. “Subsidence causes irreversible damage to infrastructure, buildings and roads.”

Contaminants in the soil, such as arsenic, can mobilize and contaminate the water when the earth changes and the water level drops. Aquifers drained by drought and pumping in coastal locations can fill with salty sea water, rendering groundwater unfit for drinking or agriculture.

“You start with a problem of water quantity, and you end up with a problem of water quality,” Ajami said.

“Excessive pumping lowers the groundwater level, creating a downward spiral in which restoring the aquifer becomes harder and harder,” added study co-author Adam Schreiner-McGraw.

The researchers offer a few suggestions for reducing the harm caused by lengthy droughts, which will become more common as the earth warms. Most climate models predict that rain will become more severe. Rainwater storage might help to replenish aquifers and speed up the recovery process.

In locations where groundwater depletion is severe, the researchers recommend that farmers increase irrigation efficiency and switch perennial crops like almonds, pistachios, and walnuts to annual, less water-intensive crops.

“We need to improve our climate projections to include groundwater, so that we can better assess what we have and how to protect it,” Ajami said. “There are ways to better manage what we have.”