Plants must be adaptable to endure natural changes, and the versatile strategies they employ should frequently be just about as variable as the changes in environment and condition to which they adjust. To adapt to dry spells, plant roots produce a water-repellent polymer called suberin that blocks water from streaming up towards the leaves, where it would rapidly vanish. Without suberin, the subsequent water misfortune would resemble leaving the tap running.

In certain plants, suberin is created by endodermal cells that line the vessels inside the roots. However, in others, similar to tomatoes, suberin is created in exodermal cells that sit just underneath the skin of the root.

The job of exodermal suberin has for some time been obscure, yet another study by analysts at the College of California, Davis, distributed on Jan. 2 in Nature Plants shows that it serves a similar capability as endodermal suberin and that without it, tomato plants are less ready to adapt to water pressure. This data could assist researchers with planning drought-safe harvests.

“It’s really the fusion of traditional and cutting-edge methodology that allows us to look at both the process that’s happening in a single cell and what you see in the entire plant.”

Siobhan Brady, professor in the UC Davis Department of Plant Biology and Genome Center, and senior author on the paper.

“This adds exodermal suberin to our tool stash of ways of aiding plants make due for longer and adapt to dry spell,” said Siobhan Brady, teacher in the UC Davis Division of Plant Science and Genome Center and senior creator on the paper. “It’s practically similar to a jigsaw bewilder—on the off chance that you can sort out which cells have changes that safeguard the plant during troublesome ecological circumstances, you can begin to pose inquiries like, assuming you develop those guards one upon the other, does it make the plant more grounded?”

In the new review, postdoctoral researcher Alex Cantó-Minister worked with Brady and a worldwide group of teammates to uncover the job of exodermal suberin and map the hereditary pathways that direct its creation.

Joining new and old-style strategies

“It’s actually the convergence of old-style and state-of-the-art procedures that allows us to take a gander at both the cycle that is occurring in a singular cell and what you find in the entire plant,” said Brady. “So going from tiny to incredibly enormous.”

New work by Prof. Siobhan Brady and Alex Cantó-Minister at the UC Davis School of Organic Sciences shows how tomato plants can make themselves more dry-spell open-minded by creating a waxy substance, suberin, in their foundations. Credit: TJ Ushing/UC Davis School of Natural Sciences

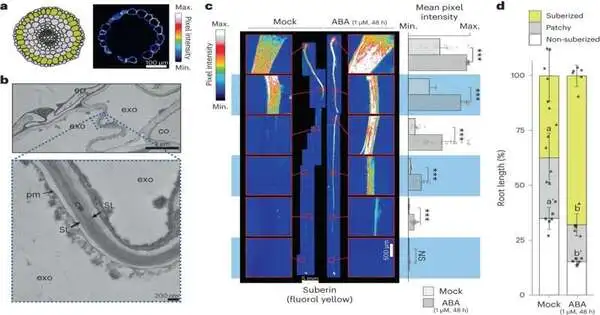

Brady, Cantó-Minister, and associates began by distinguishing the qualities that are all effectively utilized by root exodermal cells. Then, at that point, they performed quality altering to make freak kinds of tomato plants that needed utilitarian variants of a few qualities they thought may be engaged with suberin creation. They found seven qualities that were fundamental to Suberin’s statement.

Then, the scientists tried exodermal suberin’s job in dry season resilience by uncovering a portion of the freak tomato plants to a ten-day dry spell. For these examinations, the specialists zeroed in on two qualities: SIASFT, a catalyst engaged with suberin creation, and SlMYB92, a record factor that controls the outflow of different qualities engaged with suberin creation.

The trials affirmed that the two qualities are fundamental for suberin creation and that without them, tomato plants are less ready to adapt to water pressure. The freak plants developed as well as should-be-expected plants when they were very much watered, yet turned out to be essentially more shriveled following ten days with no water.

“In both of those situations where you have transformations in those qualities, the plants are more focused on them, and they’re not ready to answer dry season conditions,” Brady said.

Having shown Suberin’s worth in a nursery setting, the specialists currently plan to test Suberin’s dry spell sealing expected in the field.

“We’ve been chipping away at taking this finding and placing it into the field to attempt to make tomatoes more dry-spell lenient,” Brady said.

More information: Alex Cantó-Pastor et al, A suberized exodermis is required for tomato drought tolerance, Nature Plants (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41477-023-01567-x