A multinational team of scientists published a paper in Nature that gives convincing evidence for a relationship between astronomically-driven climate change and human evolution.

The team of experts in climate modeling, anthropology, and ecology was able to determine which environmental conditions archaic humans likely lived under by combining the most extensive database of well-dated fossil remains and archeological artifacts with an unprecedented new supercomputer model simulating Earth’s climate history of the past 2 million years.

Climate change’s impact on human evolution has long been suspected, but proving it has been challenging due to a scarcity of climate records near human fossil-bearing sites. To avoid this issue, the researchers researched what the climate was like in their computer simulations in the eras and places where humans lived, according to the archeological record. This indicated the preferred environmental conditions of various hominin populations. The following hominin species are considered in this study: Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis, Homo heidelbergensis (including African and Eurasian populations), Homo erectus, and early African Homo (including Homo ergaster and Homo habilis). The scientists then searched the model for all the places and times when those conditions happened, creating time-evolving maps of putative hominin homes.

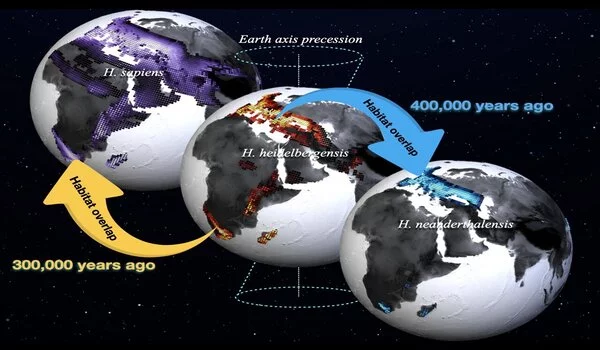

Even though different groups of archaic humans preferred different climatic environments, their habitats all responded to climate shifts caused by astronomical changes in the earth’s axis wobble, tilt, and orbital eccentricity over timescales ranging from 21 to 400 thousand years, explained Axel Timmermann, lead author of the study and Director of the IBS Center for Climate Physics (ICCP) at Pusan National University in South Korea.

The scientists repeated their research, but with the ages of the fossils shuffled like a deck of cards, to assess the durability of the link between climate and human habitats. If the historical evolution of climatic variables had no effect on where and when humans lived, both strategies would produce the same habitats. However, when utilizing the scrambled and realistic fossil ages, the researchers discovered considerable discrepancies in the habitat patterns of the three most recent human lineages (Homo sapiens, Homo neanderthalensis, and Homo heidelbergensis).

At least during the last 500 thousand years, the true chronology of previous climatic change, including glacial cycles, played a critical influence in deciding where distinct hominin groups lived and where their remains have been discovered, Prof. Timmermann stated.

“The following issue we set out to answer was whether the habitats of various human species overlapped in space and time. Past contact zones contain critical information on probable species succession and admixture. Prof. Pasquale Raia of the Università di Napoli Federico II in Naples, Italy, gathered the dataset of human fossils and archeological objects utilized in this study with his research team. The researchers then derived a hominin family tree from the contact zone analysis, according to which Neanderthals and likely Denisovans descended from the Eurasian clade of Homo heidelbergensis around 500–400 thousand years ago, whereas Homo sapiens can be traced back to late Homo heidelbergensis populations in Southern Africa around 300 thousand years ago.

Dr. Jiaoyang Ruan, co-author of the study and postdoctoral research fellow at the IBS Center for Climate Physics, says “Our climate-based reconstruction of hominin lineages is quite similar to recent estimates obtained from either genetic data or analysis of morphological differences in human fossils.”

The new study was made feasible by the use of Aleph, one of South Korea’s fastest supercomputers. The Alephclimate model simulation, located at the Institute for Basic Science’s headquarters in Daejeon, ran nonstop for nearly six months to complete the most comprehensive climate model simulation to date. The model generated 500 terabytes of data, enough to fill several hundred hard drives, stated Dr. Kyung-Sook Yun, the experiments’ lead researcher at the IBS Center for Climate Physics. Dr. Yun adds that it is the first continuous simulation with a cutting-edge climate model that covers the last 2 million years of Earth’s environmental history, representing climate responses to the waxing and waning of ice sheets, changes in past greenhouse gas concentrations, and the marked transition in the frequency of glacial cycles around 1 million years ago.

Until now, the paleoanthropological community has not fully exploited the promise of such continuous paleoclimate model simulations. Our research clearly demonstrates the need to use well-validated climate models to answer fundamental questions about our human beginnings. ” Prof. Christoph Zollikofer, co-author of the study and professor at Switzerland’s University of Zurich, says

“Even though different groups of archaic humans preferred different climatic environments, their habitats all responded to climate shifts caused by astronomical changes in earth’s axis wobble, tilt, and orbital eccentricity with timescales ranging from 21 to 400 thousand years,”

Axel Timmermann

Beyond the subject of early human habitats and the periods and places of human species’ origins, the research team looked into how people may have adapted to changing food resources over the last 2 million years. When we examined the data for the five major hominin groupings, we noticed an intriguing pattern. Around 2-1 million years ago, early African hominins preferred stable weather conditions. As a result, they were limited to very tiny livable passages. Following a major climatic transition around 800,000 years ago, a group known as Homo heidelbergensis adapted to a much wider range of available food resources, allowing them to become global wanderers, reaching remote regions in Europe and eastern Asia, “said Elke Zeller, Ph.D. student at Pusan National University and co-author of the study.”

Our research shows that climate played a critical influence in the evolution of our genus Homo. We are who we are because we have been able to adapt to modest variations in the past climate over millennia, “Prof. Axel Timmermann says.