Footprints discovered in 1978 by paleontologist Mary Leakey and her team in Laetoli, Tanzania, are the oldest unequivocal evidence of upright walking in the human lineage. The bipedal trackways have been around for 3.7 million years. Another set of mysterious footprints was partially excavated at nearby Site A in 1976 but dismissed as the work of a bear. According to a new study published in Nature, a recent re-excavation of the Site A footprints at Laetoli and a detailed comparative analysis reveal that the footprints were made by an early human — a bipedal hominin.

“Given the increasing evidence for locomotor and species diversity in the hominin fossil record over the last 30 years,” says lead author Ellison McNutt, an assistant professor of instruction at Ohio University’s Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. She began her research as a graduate student at Dartmouth College in Ecology, Evolution, Environment, and Society, where she focused on the biomechanics of walking in early humans and used comparative anatomy, including that of bears, to understand how the heel bone contacts the ground (a foot position called “plantigrady”).

The bipedal (upright walking) footprints at Laetoli Site A captivated McNutt. The impressive trackway of hominin footprints at Sites G and S are generally accepted as Australopithecus afarensis – the species of the famous partial skeleton “Lucy.” However, because the footprints at Site A were so dissimilar, some researchers suspected they were made by a young bear walking upright on its hind legs.

Through this research, we now have conclusive evidence from the Site A footprints that different hominin species were walking bipedally on this landscape but in different ways on different feet.

Jeremy DeSilva

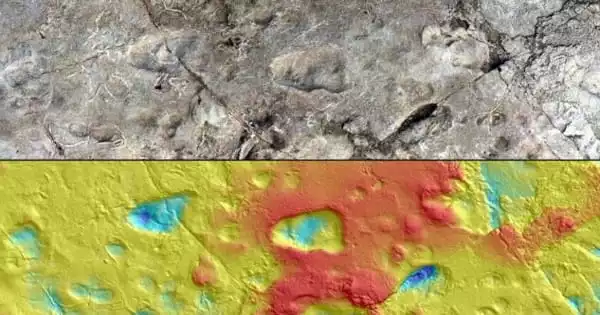

In order to determine who left the Site A footprints, an international research team led by co-author Charles Musiba, an associate professor of anthropology at the University of Colorado Denver, traveled to Laetoli in June 2019 and re-excavated and thoroughly cleaned the five consecutive footprints. They discovered evidence that the fossil footprints were created by a hominin, such as a large impression for the heel and big toe. The footprints were measured, photographed, and three-dimensionally scanned.

The Laetoli Site A tracks were compared to those of black bears (Ursus americanus), chimps (Pan troglodytes), and humans (Homo sapiens). They collaborated with co-authors Ben and Phoebe Kilham, who run the Kilham Bear Center, a black bear rescue and rehabilitation facility in Lyme, New Hampshire. They discovered four semi-wild juvenile black bears with feet similar to the Site A footprints at the Center. Each bear was enticed with maple syrup or apple sauce to stand up and walk on their hind legs across a mud-filled trackway in order to capture their footprints.

More than 50 hours of video footage of wild black bears was also obtained. The bears walked on two feet for less than 1% of the total observation time, making it unlikely that a bear made the footprints at Laetoli, especially since no footprints of this individual walking on four legs were discovered.

“When bears walk, they take very wide steps, wobbling back and forth,” says senior author and Dartmouth associate professor of anthropology Jeremy DeSilva. “They are unable to walk with a gait similar to the Site A footprints because their hip musculature and knee shape do not allow for that kind of motion and balance.” According to the researchers, bear heels taper and their toes and feet are fan-like, whereas early human feet are squared off and have a prominent big toe. Surprisingly, the Site A footprints show a hominin crossing one leg over the other as it walked, a gait known as “cross-stepping.”

“Although humans do not typically cross-step,” McNutt explains, “this motion can occur when one is attempting to reestablish their balance. The Site A footprints could have been caused by a hominin walking across an uneven surface.”

The team discovered that chimps have relatively narrow heels compared to their forefoot, a trait shared by bears, based on footprints collected from semi-wild chimps at Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary in Uganda and two captive juveniles at Stony Brook University. However, the Laetoli footprints, including those at Site A, have broad heels in comparison to their forefoot.

The impressions of a large hallux (big toe) and a smaller second digit were also found in the Site A footprints. The difference in size between the two digits was comparable to humans and chimps, but not black bears. These details support the theory that the footprints were made by a hominin walking on two legs. However, when the Laetoli footprints at Site A are compared to the inferred foot proportions, morphology, and likely gait, the results show that the footprints at Site A are distinct from those of Australopithecus afarensis at Sites G and S.

“Through this research, we now have conclusive evidence from the Site A footprints that different hominin species were walking bipedally on this landscape but in different ways on different feet,” says DeSilva, an expert on the origins and evolution of human walking. “This evidence has been available since the 1970s. It only took the rediscovery of these amazing footprints and a more thorough analysis to get us here.”