El Dorado was a mythological city in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries that was claimed to be wealthy in gold. El Dorado’s rumored location has been challenged by several sources, but it is often assumed to be in South America.

El Dorado was sought after by many explorers and those seeking gold or wealth. According to the magazine The Historian, El Dorado, however, was a composite of various tales rather than a single fixed location.

El Dorado is a figure in some versions, a lake or a valley in others. According to the BBC, the legend of El Dorado had been around for three centuries by 1835, but its origins and whether a true city of gold existed are still debated.

El Dorado’s Origin

In his poetry, Juan de Castellanos, a conquistador-turned-priest, featured one of the most famous El Dorado origin myths in his history of Spanish gallantry in the Americas, “Elegas de varones ilustres de Indias,” presumably written in the 1570s.

According to the World History Encyclopedia, the narrative is about the chief of a Muisca tribe who lived on a huge plateau high in the eastern range of the Andes in what is now Colombia, which was known to the conquistadors as Cundinamarca.

According to legend, the leader would cover himself in turpentine and gold dust once a year, and this is where the name “el Dorado,” which means “the golden one,” comes from.

The chief, according to Castellanos, carried a barge out into the middle of Lake Guatavita, a small, nearly circular crater lake sunk into the mountain. As he offered a sacrifice of gold and emeralds to the lake, the chief’s people watched on, their voices lifted in song. Then he dove in, signaling the start of the event.

This rite has never been witnessed by anyone. It was claimed to have been abandoned 40 or 50 years before the arrival of the Spaniards. When the Spanish first encountered it, it was already a commemorative practice, as described here.

Another original story.

The second version of the El Dorado origin myth is dated 1541, roughly 20 years after Cortez vanquished the Aztecs and eight years after Francisco Pizarro assassinated the Incan emperor Atahualpa. At this point in history, the Spanish had not yet traveled into much of the continent, so the majority of the continent remained undiscovered by Europeans.

The 1541 version of the El Dorado story is set in Quito, Ecuador, and is based on the writings of a conquistador named Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo. This land had just been acquired as part of the Spanish conquest of the Incas at the time.

According to Oviedo, quoted in the book “Mourning El Dorado” (University of Virginia Press, 2019), El Dorado was a “great lord or monarch [who] constantly goes about covered with gold… as fine as ground salt; for it is his opinion that wearing any other adornment is less beautifying… but powdering one’s self with gold is an extraordinary thing, unusual and new and more costly,” according to Oviedo, quoted in the book “Mourning El Dorado.”

Pizarro’s The Search for El Dorado

In February 1541, Gonzales Pizarro, a Spanish conquistador, collected a small band of men and headed off from Quito, Ecuador, in pursuit of the mythical king of El Dorado’s territory. In his own descriptions of his journey, Pizarro refers to El Dorado as a lake rather than a man. A third contemporary source, chronicler Pedro de Cieza de León, describes El Dorado as a valley in his account of the same trip.

With several hundred conquistadors (sources vary between 220 and 340) and 4,000 local servants, Pizarro set out east from Quito. They were shackled and chained, along with horses, llamas, 2,000 hogs, and an equal number of hunting dogs.

Pizarro anticipated finding civilisation in the near future, with wide terrain, tilled fields, villages, and towns. Instead, he found nothing but hardship, famine, and misery while traveling for weeks and months through the darkness of the rainforest during the rainy season, across mountains, marshes, and rivers, as Cieza de León put it.

The Spanish abducted and interrogated native individuals along the way. They were tortured when they didn’t provide Pizarro with the answers he desired. Things became dire as the year came to a close. The hogs were all dead.

They arrived at a large river, most likely the Coca, in what is now northern Ecuador, close to the equator. According to the book “River of Darkness,” a local tribal chief named Delicola, who had heard of the Spanish cruelties against individuals they interrogated, told them what they wanted to hear (Bantam 2011).

He assured them there were “extremely huge populations farther downriver” and “very rich countries full of powerful lords” downriver. Pizarro had a boat built, which he intended to use to transport men and supplies downstream while the remaining men and horses walked along the shore. They walked for 43 days, but there was little food and no one to be found.

In December 1541, Francisco de Orellana, one of Pizarro’s troops, volunteered to take the boat and fifty men to collect supplies and return in December. He promised Pizarro that he would “bring back foodstuffs as quickly as he could.” Orellana did locate food, but he never came back.

According to the book “Expeditions into the Valley of the Amazons,” he and his soldiers instead discovered the Amazon, which they called the Maraón, and rode its length for months before reaching the Atlantic on Aug. 26, 1542. Forgotten Books (Forgotten Books, 2018).Orellana claimed he didn’t have a choice but to keep going.

According to Pizarro, it was treason. He turned his remaining soldiers around and walked back to Quito slowly. Their dogs and horses were eaten, and their saddles and stirrup leathers were boiled and burned over ashes. They made it to Quito in June, but in shambles.

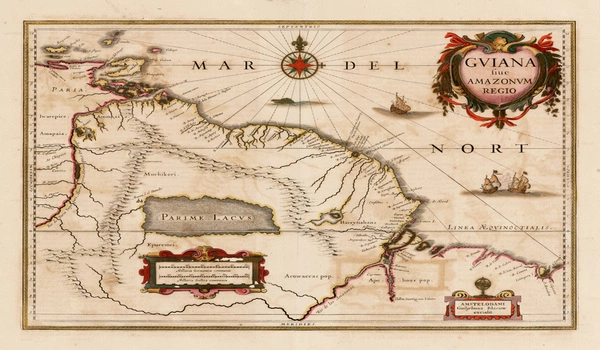

The legend of El Dorado became one of the primary motivators for European exploration of South America north of the equator, as shown in this account.

The Conquerors from Germany

Pizarro’s was the first official search for El Dorado. However, as word of the golden land spread, more conquistadors began to pretend that their travels into the interior were in search of it.

According to Jose Ignacio Avellaneda’s article “The Men of Nikolaus Federmann,” this is proven in the stories of Sebastian de Benalcázar, Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, and Nikolaus Federmann (“The Americas,” Vol. 43, No. 4, Apr., 1987). Nikolaus Federmann’s presence among the conquistadors in Colombia reveals that, while the vast majority of them were Spanish, the picture is more complicated than commonly assumed.

The average conquistador party was made up primarily of poor Spanish men from Andalusia, Castile, and Extremadura who had traveled to Seville and then to San Lcar de Barrameda, where the Guadalquivir flows into the Atlantic and where most expeditions to South America began.

This group, however, includes Dutch, Flemish, German, Italian, Albanian, English, Scots, and other nationalities. During some of the 1530s, the Germans were by far the most dominant of these.

According to the book “Man’s Worldly Goods” (Hesperides, 2008), the emperor Charles V owed the Welser banking dynasty of Augsburg 143,000 florins in 1528. Because they couldn’t pay, Charles granted them the province of Venezuela instead, holding 20% of any treasure found and the same percentage of slaves-a state of affairs that continued until 1546.

Federmann’s mission was one of several German-led conquistador expeditions that crisscrossed the region at this time; other German conquistadors were George Hohermuth and Philip von Hutten.

One of the earliest, led by Ambrosius Ehinger, managed to amass 405 pounds (184 kilograms) of gold through extortion and brutality. Almost everyone involved, including Ehinger, died as a result of this. After two years apart, the survivors returned to Coro, Venezuela’s capital, and disclosed that they had buried the riches behind a tree, from which they had never recovered.

More information about El Dorado can be found on the World History Encyclopedia website. You can also watch this video from the Science Channel.