According to a new study led by the University of Eastern Finland, vegetation is decreasing along elephant migration routes in Namibia. Human development creates impediments, such as fences, that disrupt the movement of wild animals, exacerbating the loss of vegetation cover.

According to a study based on extensive remote sensing data, vegetation along elephant migration routes in Namibia has decreased. Human habitation and fences, as well as other artificial obstacles, influence the movements of wild animals, contributing to the acceleration of vegetation decline. Meanwhile, increased plant life was observed in areas where intensive farming and cattle grazing were practiced.

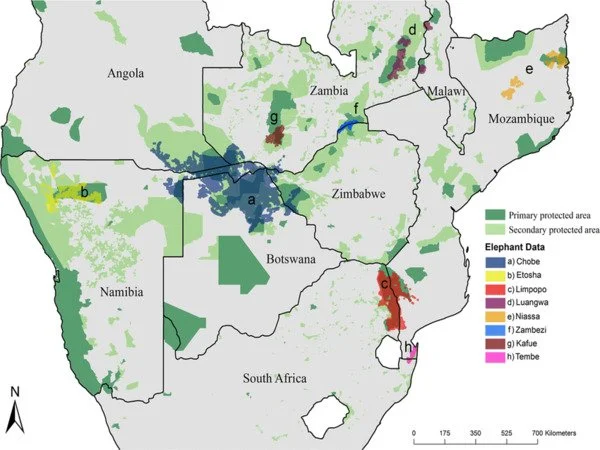

Researchers from the University of Eastern Finland and the University of Namibia used remote sensing data to determine how elephants and other large herbivorous mammals affect vegetation and its structure in Namibia’s Zambezi region from 2002 to 2021. The study also looked at the effects of human activity on vegetation and wild animal movement. Sensor, a scientific journal, published the findings.

A better understanding of how wild animals affect vegetation provides tools for improving the management of wild animals and natural resources. The study’s findings will serve as a reference for policy and decision makers. Future studies should consider integrating higher resolution multi-platform datasets for detailed microanalysis and mapping of vegetation cover change.

Professor Alfred Colpaert

The Zambezi region now has approximately 12,000 elephants. Since 1989, when the elephant population was less than 1,500 individuals, the population has nearly tenfold increased. According to the study, the loss of vegetation was greatest in areas with large elephant populations. The vegetation in elephant migration corridors in national parks and nature reserves suffered the most damage.

Elephants’ unique communication abilities are critical to their survival. Aside from trumpeting and rumbling, the animals make a variety of other sounds, including barks, roars, snorts, screams, squeals, groans, and cries. When there is danger, they also use jackhammer-like, ear-splitting blasts to alert others to form a protective circle around the family’s younger members.

The most common vocalizations are the aforementioned growling or rumbling noises, which researchers believe are unique to each elephant. These rumbles can cause seismic vibrations, which receiving elephants detect through the soft skin on the pads of their feet; at times, they lay their trunks on the ground to detect vibrations in the earth.

“A better understanding of how wild animals affect vegetation provides tools for improving the management of wild animals and natural resources,” says University of Eastern Finland Professor Alfred Colpaert. “The study’s findings will serve as a reference for policy and decision makers,” the researchers wrote. “Future studies should consider integrating higher resolution multi-platform datasets for detailed microanalysis and mapping of vegetation cover change,” the researchers write.

Among other things, the study made use of MOJDIS satellite data, which is useful for examining changes in the soil over time. More advanced geospatial methods were used to analyze the time series materials, allowing us to distinguish between soil degeneration caused by human action and that caused by natural climatic factors.

The total population of African elephants is estimated to be between 400,000 and 660,000 individuals. Individual forest and savanna populations have not been reported by the IUCN—The World Conservation Union due to the need for additional genetic and phylogenic research for various hybrid classifications. The African elephant is currently listed as threatened by the IUCN.

The IUCN has classified all Asian elephant subspecies as endangered, with a total population estimated to be between 25,600 and 32,750 individuals. The Indian elephant (E.m.indicus) has the largest population, with estimates ranging from 20,000 to 25,000 individuals. The Sumatran and Sri Lankan elephants are critically endangered, with Sumatran elephant populations estimated to be between 2,440 and 3,350 and Sri Lankan elephant populations estimated to be between 3,160 and 4,400. The Borneo elephant is the most endangered Asian subspecies, with population estimates ranging from 1,000 to 1,500 individuals.