It appears to be adequately coherent: even in their earliest history, people probably required something to haul their children around in as they moved from one spot to another. But since minimal hard proof of this exists—no newborn child sling textures detectable in archeological digs, and not many ancient child entombments, other than—it’s been impossible to say that the training really occurred.

However, new exploration by a group of Université de Montréal researchers contends for proof of the utilization of child transporters around a long time back, illuminating how kids were really focused on in ancient times and how they were connected socially to their local area.

Driven by Claudine Rock Miguel, an Arizona State College (ASU) anthropologist currently filling in as a visitor scientist in the lab of UdeM humanities teacher Julien Riel-Salvatore, the group used creative logical techniques to remove hard-to-get data about punctured shell dabs tracked down in the entombment of a 40-to 50-day-old female child, nicknamed Neve, at the cavern site of Arma Veirana, in Liguria, Italy.

The group’s discoveries are distributed in the Diary of Archeological Strategy and Hypothesis. In their review, Rock Miguel and her partners describe how they utilized a top-quality 3D photogrammetry model of the entombment together with tiny perceptions and microCT check examinations of the dabs to record exhaustively the way that the internment occurred and how the dots were logically involved by Neve and her local area throughout everyday life and in death.

“Given the time and work required to produce and reuse beads throughout time, it is intriguing that the community chose to include these beads in the burial of such a young person. According to our findings, the beads and pendants most likely ornamented Neve’s carrier, which was buried alongside her.”

Claudine Gravel-Miguel, an Arizona State University (ASU) anthropologist

The results show that the dabs were sewn onto the piece of cowhide or fabric that was utilized to wrap Neve for her internment. This design contained in excess of 70 little punctured marine shells and four major punctured bivalve pendants not tracked down in other ancient locales. The majority of the dots bear weighty indications of purpose, which could never have been created during Neve’s short life, the researchers notice.

This shows that the dots had been worn for an extensive timeframe by somebody in the baby’s local area before they were given over to her, potentially as legacies, or maybe even utilized as security against negative powers.

“Given the work expected to make and reuse dabs over the long haul, it is fascinating that the local area chose to leave behind these dots in the entombment of such a youthful individual,” said Rock Miguel. “Our exploration proposes that those dabs and pendants probably enhanced Neve’s transporter, which was covered with her.”

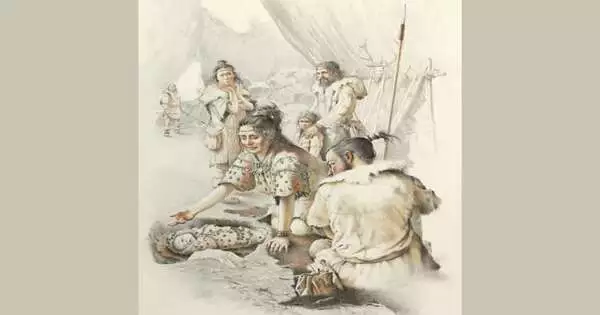

Depending on ethnographic perceptions of how child transporters are enhanced and utilized in some advanced agrarian social orders, the review proposes that Neve’s people group might have adorned her transporter with dots intended to safeguard her against “evil.” Nonetheless, as her demise flagged that those dabs had fizzled, it would have been extraordinary to cover the transporter as opposed to reuse it.

The new examination adds to the developing writing of ancient childcare and the logical use and reuse of dots to safeguard people and keep up with the social connections inside a local area, added Riel-Salvatore.

“This paper contributes really unique data on the paleohistory of childcare,” he said. “It spans the science and craft of paleontology to get to the ‘human’ component that drives the sort of examination we do.”

More information: C. Gravel-Miguel et al, The Ornaments of the Arma Veirana Early Mesolithic Infant Burial, Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s10816-022-09573-7