A focus on canine cerebrum networks uncovers that during mammalian mind development, the job of the cingulate cortex, a reciprocal design found somewhere down in the cerebral cortex, was halfway taken over by the sidelong cerebrums, which control critical thinking, task-exchanging, and objectively coordinated conduct. A brand-new canine resting-state fMRI brain atlas is used in the study. This atlas can be used to better understand diseases characterized by dysfunctional integration and communication between brain regions.

Using fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging), researchers can identify and observe which areas of the dog’s brain are active when the dog responds to external stimuli. This allows them to deduce how dogs think from their behavior. Superior dog training techniques and knowledge of the evolutionary processes that resulted in the development of human brain function are made possible by the method’s identification of the brain mechanisms that influence the dog’s learning and memory.

Since 2006, the Eötvös Loránd University Department of Ethology (ELTE) has been at the forefront of developing the method for canine fMRI measurements. The preparation strategy for pet canines was created by Márta Gácsi, who has likewise made huge commitments to the presentation of canine preparation in Hungary. She used a lot of the techniques she learned there and added socially motivated training based on rival training principles she learned from ethological research.

“We’ve decided to create a dog brain atlas that organizes anatomical regions into functional networks, illustrating which regions belong to a task type and displaying their locations,”

Dora Szabo, first author of the study published in Brain Structure and Function.

“In this methodology, the student is emphatically roused to gain proficiency with the undertaking by noticing the craft crafted by a generally prepared canine and wanting the recognition he gets for it. The trained dog is capable of doing so and eager to do so as a result of fMRI training. “Lie still in the X-ray scanner for eight minutes, in return for anticipated petting and treats.”

Lately, canine fMRI has commonly elaborated on playing sounds to the creatures and examining which cerebrum regions are initiated during the mind’s handling of the sounds.

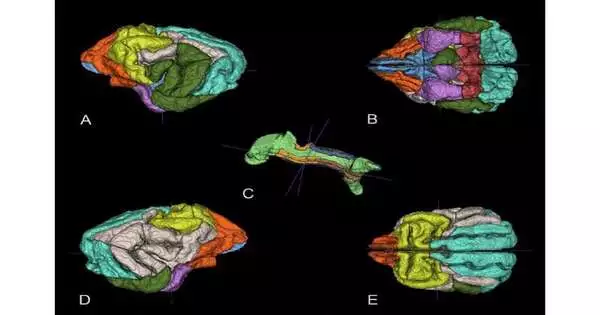

Cerebrum movement signals are ordinarily projected onto a physical map book to lay out which mind locale is impacted.

The issue, on the other hand, is that functional activities are irregular and do not always adhere to regular boundaries that are defined by anatomy. A functional brain network is made up of parts of the brain that work together to process particular inputs, i.e., in sync. The study’s first author, Dora Szabo, stated, “We have decided to create a dog brain atlas that organizes anatomical regions into functional networks, illustrating which regions belong to a task type and showcasing their locations.”

New atlas for dog brain researchers

A new atlas for dog brain researchers 33 trained family dogs were included in the study to create the functional brain atlas. During the fMRI recording, the canines were not given any errand other than to lie still in the scanner. This is the so-called resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (rs-fMRI), or rs-fMRI for short. In a “resting state,” the subject is not engaged in any particular activity or focused on or thinking about anything in particular. Researchers can study brain networks and connections by discovering which brain regions are functionally related to one another and which are the most closely connected.

Utilizing network theory with the assistance of Milan Janosov, a network and data scientist at Central European University, the initial method was further improved. New canine MRI brain atlases that reflect the anatomical regions at the required resolution enabled researchers to study the strength of connections between network members or between networks, as well as to compare species due to the large number of dogs measured. Prior research could only describe model-based networks, regardless of anatomical boundaries.

The study found that the networks in the lateral frontal lobe (frontoparietal) that control problem-solving, task-switching, and goal-directed behavior play a smaller role in dogs than in humans. These networks are dominated by different parts of the brain in humans. In their place, the cingulate cortex, a respective construction found somewhere down in the cerebral cortex, assumes a focal role. It is involved in the processing of rewards and the regulation of emotions, among other important processes. The cingulate cortex in dogs is relatively bigger than in people.

The effects of getting older

The researchers measured dogs of all ages, the oldest of which was 14 years old. To take accurate measurements, the dogs must remain motionless, as previously stated.

“The data showed that older dogs had a slight problem keeping their initial position. However, given that even in their instance, the head displacement was less than 0.4 mm, this disparity was extremely small. According to Eniko Kubinyi, a senior researcher studying cognitive aging in dogs, “they are similar to humans in this aspect, as older people also find it more challenging to maintain stillness for extended periods of time than younger individuals do.”

The study provides a glimpse into the evolution of the human brain and suggests that frontoparietal regions partially assumed the cingulate cortex’s function during mammalian brain evolution. Furthermore, the new rs-fMRI mind map book can help with the examination of conditions in which joining and correspondence across cerebrum regions are disabled, bringing about a useless division of undertakings. Maturing, uneasiness, and mental problems are a few instances of such circumstances.

More information: Dóra Szabó et al, Central nodes of canine functional brain networks are concentrated in the cingulate gyrus, Brain Structure and Function (2023). DOI: 10.1007/s00429-023-02625-y