Humans are home to nearly 300 parasitic worm species and over 70 single-celled parasites. Over a billion people were found to be infected with helminths in 2020 alone, causing chronic inflammation. Previous research has shown that certain biological factors, such as higher baseline inflammation caused by high pathogen (parasite) environments, contribute to the development of depression. A higher prevalence of psychiatric disorders in more populous countries suggests that parasite infections may play a role in a variety of mental illnesses.

New research into the effects of common parasite infection on human behavior could aid in the development of treatments for schizophrenia and other neurological disorders. According to scientists, those infected with T. gondii, which currently infects 2.5 billion people worldwide and causes the disease, exhibit behavioral changes. Toxoplasmosis may be associated with decreased levels of norepinephrine, a chemical released in the brain as part of the stress response. Norephinephrine also regulates neuroinflammation, which is the activation of the brain’s immune system in response to infection.

Neuropsychological disorders such as schizophrenia, Alzheimer’s disease, and ADHD have been linked to norepinephrine and neuroinflammation. Although T. gondii infection is usually asymptomatic in humans, it can cause headaches, confusion, and seizures in others, as well as increased susceptibility to schizophrenia and can be fatal in immunocompromised patients.

Our insight connects the two opposing theories for how Toxoplasma alters host behavior and this may apply to other infections of the nervous system. One school believes that behaviour changes are invoked by the immune response to infection and the other that changes are due to altered neurotransmitters.

Glenn McConkey

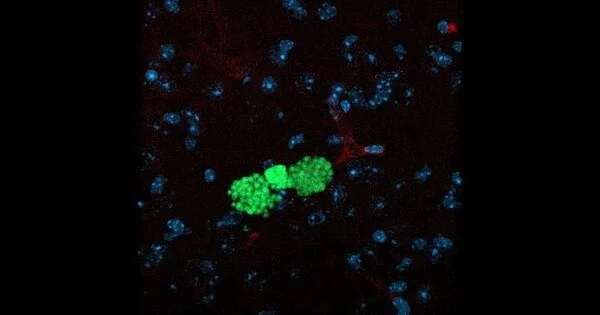

T. gondii can only reproduce sexually in cats. It forms cysts, which are excreted by the cat. It enters new hosts through ingestion of anything contaminated by these cysts, such as water, soil, or vegetables; blood transfusions containing unpasteurized goat’s milk; eating raw or undercooked meat; or transmission from mother to fetus.

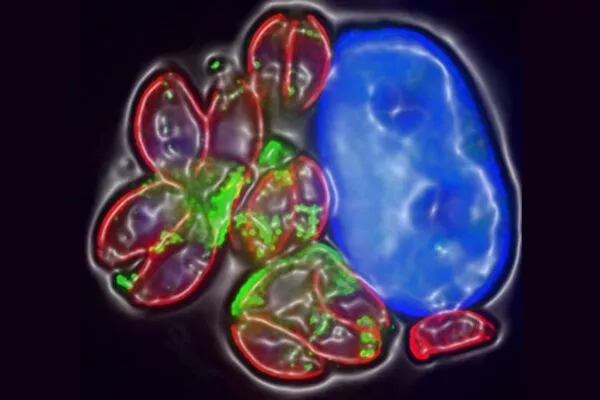

After a few weeks, the infection enters a dormant phase, whereupon cysts form in the brain. They can remain there for many years, possibly for life. It is during this stage that infection decreases the regulator of the brain’s immune response norepinephrine.

The mechanisms by which the parasite affects brain function have been poorly understood. But research led by the University of Leeds and Université de Toulouse now suggests that the parasite’s ability to reduce norepinephrine interrupts control of immune system activation, enabling an overactive immune response that may alter the host’s cognitive states.

The findings – Noradrenergic Signaling and Neuroinflammation Crosstalk Regulates Toxoplasma gondii-Induced Behavioral Changes – have been published in Trends in Immunology.

Glenn McConkey, Associate Professor of Heredity, Disease, and Development at Leeds’ School of Biology, who published the research, said: “Our insight connects the two opposing theories for how Toxoplasma alters host behavior and this may apply to other infections of the nervous system. One school believes that behaviour changes are invoked by the immune response to infection and the other that changes are due to altered neurotransmitters.”

“This research will contribute to the great need in understanding how brain inflammation is connected to cognition, which is essential for the future development of antipsychotic treatments.”

#Parasite Infection Discovery Could Assist #Mental #Health Treatments via @neurosciencenew https://t.co/iHQP406NMI

— Francisco Tavira (@FranTavira) November 22, 2020