The element lithium is powering the world’s electric vehicles, making it a critical component in the fight against carbon pollution. According to a study published today in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B, the combination of lithium mining and climate change in the Andes Mountains may be negatively affecting flamingo populations.

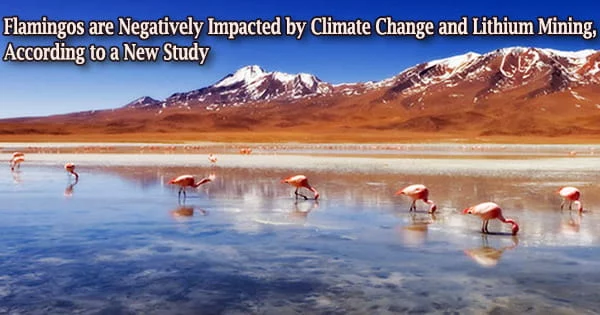

The research looked at the impact of lithium mining and climate change on small saltwater lakes in the Chilean Andes, where flamingos congregate for eating and mating.

The findings demonstrate that two species of flamingos that exclusively breed in these mountains had lost 10 to 12 percent of their population in just 11 years, but only at the mined lake.

“Given how rapidly our demand for lithium is growing, there is a great need to understand what negative effects its production might be having on biodiversity and especially those species, like flamingos, that are important to local economies,” says Dr. Nathan Senner, a population biologist at the University of South Carolina and co-author on the paper.

The ‘Lithium Triangle’ of Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina produces the majority of the world’s lithium. Meanwhile, the region is home to three flamingo species: Andean, James’, and Chilean, two of which breed nowhere else on the planet and are the backbone of the region’s tourist sector.

The study, which comprised scientists from Spain, Montana, and Chile, focused on five lakes in the Chilean Andes, which are part of the Lithium Triangle, including the Salar de Atacama, where most of Chile’s lithium mining takes place.

The problem is that, in the Salar de Atacama, in addition to the changes caused by climate change across the region, lithium mining is reducing water levels and increasing disturbances for flamingos. This means years with sufficient water for flamingos to breed occur less frequently and fewer flamingos are now present, even when there is enough water.

Dr. Jorge Gutiérrez

Climate change is causing the lakes in the region to diminish, according to the scientists. When the water level in a lake drops, food levels drop, and the number of breeding flamingos drops as well.

However, the scientists discovered that flamingo populations have not yet begun to fall significantly. Instead, flamingo numbers have decreased only in the Salar de Atacama.

For the time being, mining has had a minor influence on the region, and the overall flamingo population has remained stable, owing to the birds’ ability to migrate to new lakes in search of better conditions, according to Senner. However, if lithium mining develops to fulfill international demand for the metal, this may not be the case in the future.

“The problem is that, in the Salar de Atacama, in addition to the changes caused by climate change across the region, lithium mining is reducing water levels and increasing disturbances for flamingos,” says Dr. Jorge Gutiérrez, an ecologist at the Universidad de Extremadura in Spain who led the study. “This means years with sufficient water for flamingos to breed occur less frequently and fewer flamingos are now present, even when there is enough water.”

The authors based their findings on 30 years of flamingo counts conducted by citizen scientists and Chilean government biologists across five saline lakes. They also used data from remote sensing to track changes in water levels and food availability in each lake over time.

This allowed researchers to look into how climatic factors influenced the availability of water and flamingo food, as well as how water and food influenced flamingo abundance.

Lithium demand has exploded in recent decades due to its application in electric vehicles, cell phones, and electronic storage devices. As a result, production in Chile is expected to increase by 2026 compared to 2018 levels, and to expand beyond the Salar de Atacama to adjacent saline lakes.

“The flamingo declines we documented in the Salar de Atacama may soon spread to the rest of the region,” says Dr. Cristina Dorador, a co-author and professor at the Universidad de Antofagasta.

“Given that two of these flamingo species breed nowhere else in the world, this could lead to dramatic declines across their entire range and severely hurt the local ecotourism industry that relies on flamingos.”

In addition to Senner, Gutierrez, and Dorador, the researchers included Johnnie Moore at the University of Montana, Patrick Donnelly at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Juan Navedo at Universidad Austral de Chile.