From the most profound seas to the most noteworthy mountains, human-caused environmental change is having a significant effect on creatures and plants all over the planet, with numerous species being driven to the edge of termination by rising temperatures.

From bears to moose to lynx, and even squirrels and frogs, creatures are leaving their homes looking for cooler environments as the planet warms. As a matter of fact, generally 50% of the world’s 4,000 species are moving, with many relocating northwards towards higher latitudes.

For biologists and moderates, understanding how these species’ practical environments grow and contract with regards to a rapidly moving environment is basic. Thusly, species dissemination displays are frequently used to anticipate relocation propensities and reasonable natural surroundings for species under various ecological circumstances.

In any case, current models can create wrong and excessively hopeful outcomes since they neglect to think about a key question: could an animal category at any point reasonably arrive at a reasonable environment before it’s past the point of no return?

Not all conditions are reasonable for each specie, and creatures shift and relocate at various speeds in light of a scope of elements, like versatility, regenerative capacity, or scene highlights. In nature, this is known as a dispersal cutoff or requirement.

At the point when we ponder the effect of environmental change on species territory, we need to inquire: Where can the species reside later on under environmental change, yet more critically, might they at any point arrive?” said Bistra Dilkina, a USC software engineering academic partner and co-head of USC’s Middle for Man-made Reasoning in the Public Eye.

“We need to progressively and precisely evaluate our protection needs, and getting the right apparatus to comprehend future worries is vital.”

That is the reason Dilkina collaborated with Georgia Tech biogeographers Jenny McGuire, an associate teacher, and Ben Shipley, a Ph.D. competitor, to make MegaSDM, the main displaying apparatus that considers dispersal limits for some species, environmental models, and time spans immediately.

When given a rundown of animal groups and ecological information, the model delivers a progression of guides outlining how species move over the long run in various situations under environmental change.

A shift toward the north

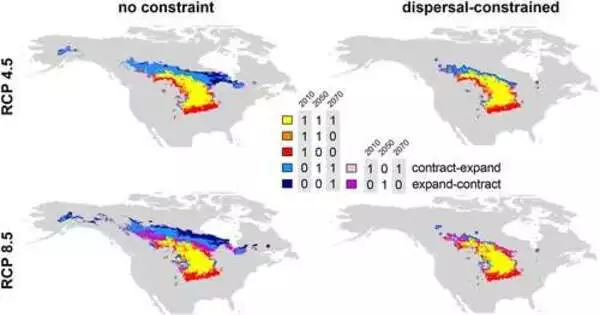

In a new paper, the group displayed 165 North American warm-blooded creatures’ conveyances in 2010 and projected them to 2050 and 2070 under two situations: with dispersal limits and without. They tracked down an anticipated decrease in general species lavishness from 2010 to 2070 across North America, and a small yet noticeable shift toward the north.

Be that as it may, the guide with dispersal limitations sounded a critical admonition: Numerous species will not be able to colonize every one of the accessible reasonable territories in 2070.

“At the point when dispersion rate is thought about, what’s in store looks more disheartening than we would have expected,” said McGuire.

“While taking a gander at changes in territory reasonableness over the long haul, we see living space shrinkage toward the south, and natural surroundings reasonableness development toward the north, as most would consider to be normal.” Be that as it may, significantly, while coordinating dispersal limits into the examination, we likewise see a great deal of the living space reasonableness gains are lost because of dispersal limits.”

Movements are made utilizing MegaSDM, which shows species range changes with dispersal requirements for Franklin’s Ground Squirrel from 2010 to 2070. “With the more naturally precise dispersal-compelled movement, you can find (in blue) that the species range doesn’t grow through time as much as with the dispersal-unconstrained liveliness,” said Shipley. Thus, the model could permit scientists to focus new light on which species are genuinely in danger of eradication because of environmental change. Previous research indicates that species with slow dispersal rates, such as primates, wenches, moles, and opossum request species, are most vulnerable, at least in the Western half of the world.

Likewise, in danger are chilly climate, high-rise species. For example, the pika, a little mountain-staying creature that can overheat and kick the bucket in temperatures as gentle as 78 degrees Fahrenheit. Regardless of declining numbers, the little warm-blooded creature has been denied imperiled species status, with studies proposing it will relocate to cooler regions upslope.

In any case, with dispersal requirements considered, what’s in store for the pika looks less hopeful.

“Pikas are probably not going to move around a great deal consistently, so their dispersal rates are very low. Therefore, regardless of whether some new reasonable living space opens up on a mountain reach toward the north, it very well may be impossible that any population of pika would lay out there, and as the environment warms, their territories will contract,” said Shipley.

“The guide without dispersal requirements might show an extension to colder and higher mountain ranges, while a dispersal-compelled guide would show a reduction in territory without a related development through time.”

Taking part in future activities

One more benefit of MegaSDM: It can integrate numerous species, time spans, and environmental situations immediately. By producing one-of-a-kind guides depicting the progressions in species ranges, it enables scientists to anticipate species circulations back and forth in order to guess where an animal type might actually reside in the future.

“The greater part of the ongoing procedures utilized by species conveyance models are static, so they just travel to a solitary time span, and they don’t consolidate parts of development across scenes,” said Shipley. Yet, MegaSDM utilizes a multi-step time approach, so you can apply these conveyance models to past or present time spans and show dynamic development, such as extending and contracting of reach sizes.

It also enables specialists to distinguish the effects of environmental change from other impediments to movement, such as urban transformation or inadmissible natural surroundings.

“In the event that we take a gander at just today, we’re not getting a full image of the multitude of various environments in which an animal group can live,” said McGuire. “The device permits us to perceive when an animal group is being confined by different sorts of effects, and it permits us to all the more likely guess where they might actually reside from here on out and to recognize expected regions for rebuilding.”

Fostering the open-source instrument required cautious framework designing and wanting to decide how to make a measured framework utilizing the least amount of memory prerequisites, said Dilkina, the Dr. Allen and Charlotte Ginsburg Early Profession Seat in Software Engineering.

To start with, the scientists displayed the territory reasonableness for species utilizing important openly accessible information, like geographic data frameworks (GIS) layers, including elevation, land cover, urbanization level, and forestation. Then, they took a gander at where these species have been distinguished, and environmental information for the present and what’s in store.

Going ahead, the group intends to utilize the apparatus to recognize species at the most noteworthy gamble with expectations of decisively executing preservation techniques, untamed life steppingstones or passages, for example, to increase the availability of saved scenes.

“Environmental change is here quicker than we expected,” said Dilkina. “Building the devices to assist us with making quantitative expectations about what will happen is critical, and I accept this will enable future activity in biodiversity preservation and environmental change alleviation endeavors.”

The review was published in Ecography.

More information: Benjamin R. Shipley et al, megaSDM: integrating dispersal and time‐step analyses into species distribution models, Ecography (2021). DOI: 10.1111/ecog.05450

Journal information: Ecography