A clinical research found that the immunotherapy medicine pembrolizumab improved survival rates in individuals with intermediate-risk head and neck cancer. A University of Cincinnati clinical trial that included an immunotherapy medicine to standard-of-care treatment regimens resulted in enhanced survival rates for patients with intermediate-risk head and neck cancer.

The experiment was directed by Trisha Wise-Draper, MD, who was also the lead author of an article summarizing its findings that was recently published in Clinical Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

Targeting the immune checkpoint

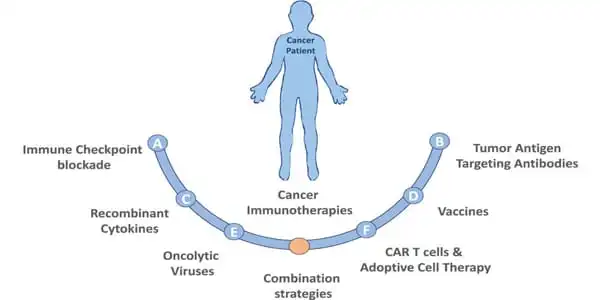

According to Draper, the research focused on adding a medication, pembrolizumab, to patients’ usual standard of care therapies. Pembrolizumab, also known as Keytruda, is an antibody used in cancer immunotherapy to treat a number of malignancies, including head and neck cancer. The medicine targets a pair of receptors that normally function to switch off the human immune system once it has completed its duty of fighting off a foreign material that causes disease.

“Once the virus or infection is cleared, you have to have a way to turn your own immune system off, to tell it that the infection is gone and it’s time to calm down,” said Wise-Draper, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology/Oncology in UC’s College of Medicine, co-leader of the Head and Neck Center of Excellence, medical director of the University of Cincinnati Cancer Center Clinical Trials Office and Lab, and UC Health physician.

Tumor cells have learned to activate the receptors that shut down the immune system, preventing immune cells from recognizing tumor cells as foreign things that the body should fight. Pembrolizumab, on the other hand, prevents the connection and keeps immune cells active, resulting in immune cells targeting malignant cells as they should.

We noticed a significant improvement in that, so we knew that pembrolizumab was obviously enhancing their chances of survival, at least when compared to historical controls. It was a fairly significant predictor of patients who were going to do well on this medication.

Wise-Draper

The medicine has been developed as a treatment for numerous malignancies, and Wise-Draper said it has showed early success as a treatment for head and neck cancers that have spread or returned after initial treatment, with early studies finding effectiveness for roughly 20% of patients treated.

“And, while we’re careful not to say cure, it does result in what are called ‘durable responses,'” she explained, referring to patients who have a good response to treatment for much longer than expected, sometimes for years, “which was a huge advancement over chemotherapy, which may have only been effective for say nine to ten months at most,” Wise-Draper said.

The hypothesis

With promising preliminary results, the UC clinical trial sought to determine whether the medicine could be used as a first treatment to prevent the cancer from reoccurring. Patients with head and neck cancer who are treated with routine surgery, radiation, and sometimes chemotherapy if risk factors merit it, see their tumors return roughly 30% to 50% of the time, according to Wise-Draper.

“So, instead of waiting for them to return, may we try to prevent them from returning? If the cancer returned, it was far more difficult to cure the second time, and there was a high failure rate in that group” She stated. “So we asked whether we might add this immunotherapy, pembrolizumab, and reduce the danger of cancer returning.”

According to Wise-Draper, the experiment was also aimed to investigate why some individuals respond to pembrolizumab while others do not. To achieve this purpose, tissue and blood samples were obtained before and after the medicine was administered in order to examine factors that contributed to patients responding to the treatment.

The trial

Patients enrolled in the trial received one dose of the medicine prior to surgery, following which they were evaluated for risk status and divided into intermediate- and high-risk groups. If a portion of the tumor remains after surgery or is not contained in a lymph node, the patient is deemed high risk.

All patients received the appropriate standard of care (radiation alone for intermediate risk or radiation and chemotherapy for high risk), as well as six additional doses of pembrolizumab after surgery.

According to Wise-Draper, the treatment caused tumors to die before surgery in over half of the patients, which is a higher percentage than when the drug was used to treat metastatic or recurrent head and neck cancer. “We could observe that many of these tumors were dying even after the first dose of pembrolizumab,” Wise-Draper explained. “That was pretty amazing because it was higher than we anticipated.”

Less than 70% of patients in the intermediate group who were treated with radiation alone after surgery remained disease-free one year later, but more than 95% of patients in the trial reported one-year disease-free survival when both radiation and pembrolizumab were used.

“We noticed a significant improvement in that, so we knew that pembrolizumab was obviously enhancing their chances of survival, at least when compared to historical controls,” Wise-Draper said. One-year disease-free survival was observed in 100 percent of individuals in whom the treatment began to destroy the tumor prior to surgery.

“It was a fairly significant predictor of patients who were going to do well on this medication,” said Wise-Draper. “Hopefully, that will help us design studies to better identify who will respond and who will not.”

A good predictor for patients who are expected to respond well to treatment will also aid in determining how therapies can be changed for patients who have surgery, pembrolizumab, chemotherapy, and radiation but do not respond well to the treatment.

“That’s basically where the research is heading today,” Wise-Draper said, “trying to understand what those biomarkers are between responders vs nonresponders and how we can design new and better focused medicines.” “We’ve identified a few of markers that will help us in the future, but we’re still doing a lot of study in that area.”

Next steps

Harvard University researchers did a study comparable to UC’s that had similar success, and the favorable findings of these experiments imply that a randomized Phase III clinical trial is worthwhile to pursue. Merck is now conducting a randomized trial comparing patients who get pembrolizumab in addition to their standard of therapy to patients who receive only the standard of care.

“That will be a much larger trial that will help show if pembrolizumab genuinely aids these groups,” Wise-Draper said of the Merck project.

At UC, research into pembrolizumab as a treatment for head and neck cancer is underway, with a new round of research aimed at learning how therapies might be better customized to each patient. Tumor traits and biomarkers that can help predict whether a patient would respond to a certain treatment can be examined before surgery, with more specific treatment plans resulting in better outcomes.

“It’s been really thrilling to have individuals do well on this study and seeing their survival rise knowing what the historical statistics were, as well as simply having a good study in general,” Wise-Draper said. “A lot of these developments happened far faster than I expected in my career, so it’s been a really exciting journey for all of us. Hopefully, there will be more to come.”

If the medicine continues to be safe and successful, Wise-Draper believes it will be a “great improvement” over the present course of care, which has a 50% recurrence rate. According to her, there is even a chance that patients will not require surgery as part of their treatment strategy. “If we had a less toxic treatment, we might be able to reduce the morbidity of surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy,” Wise-Draper added.