For the most part, discernment feels easy. Assuming that you hear a bird twittering and glance through the window, it barely feels like your cerebrum has done anything at all when you perceive that trilling critter on your windowsill as a bird.

As a matter of fact, research in mental science proposes that these sorts of sound signals can not only assist us with perceiving objects all the more rapidly, but could also modify our visual discernment. That is, match birdsong with a bird, and we see a bird; yet supplant that birdsong with a squirrel’s jabber, and we’re not exactly certain what we’re checking out.

“Your cerebrum spends a lot of energy to deal with the tactile data on the planet and to provide you with that sensation of a full and consistent insight,” said lead creator Jamal R. Williams (College of California, San Diego) in a meeting. “One way that it does this is by making inductions about what kinds of data ought to be normal.”

Albeit these “educated surmises” can assist us with handling data all the more rapidly, they can likewise steer us off track when what we’re hearing doesn’t coordinate with what we hope to see, said Williams, who directed this exploration with Yuri A. Markov, Natalia A. Tiurina (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne), and Viola S. Störmer (College of California, San Diego, and Dartmouth School).

“Your brain expends a large amount of energy processing sensory information in the world and providing you with the sensation of complete and seamless perception. It accomplishes this in part by inferring what kinds of information should be expected.”

Lead author Jamal R. Williams (University of California, San Diego)

“In any case, when people are certain about their discernment, sounds consistently adjust them from the genuine visual highlights that were shown,” Williams said.

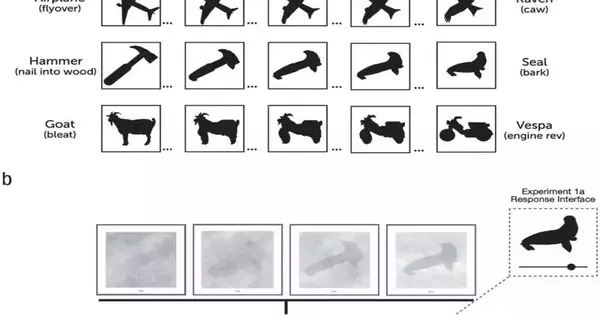

In their most memorable examination, Williams and partners gave 40 members calculations that portrayed two items at different phases of transforming into each other, for example, a bird moving toward a plane. During this visual segregation stage, the specialists likewise played one of two kinds of sounds: a connected sound (in the bird/plane model, a birdsong or the buzz of a plane) or an irrelevant sound like that of a sledge hitting a nail.

Members were then approached to review which phase of the item transformation they had been shown. To show what they reviewed, they utilized a sliding scale that, in the above model, caused the item to show up more bird-like or more plane-like. Members were found to make their article transformation determination all the more rapidly when they heard related (versus inconsequential) sounds and to move their item transformation choice to all the more intently match the connected sounds that they heard.

“At the point when sounds are connected with appropriate visual highlights, those visual elements are focused on and handled all the more immediately, as contrasted with when sounds are inconsequential to the visual highlights.” “In this way, if you hear a bird’s song, anything bird-like is focused on admission to visual discernment,” Williams explained.”We observed that this prioritization isn’t absolutely facilitative and that your view of the visual article is more bird-like than if you had heard a plane soaring over.”

In their subsequent examination, Williams and partners investigated whether this impact was well defined for the visual-segregation period of perceptual handling or, on the other hand, in the event that sounds could rather shape visual discernment by affecting our dynamic cycles. To do as such, the scientists gave 105 members a similar undertaking, yet this time they played the sounds either while the item transformation was on screen or while members were making their article transformation choice after the first picture had vanished.

As in the primary examination, sound information was found to impact members’ speed and accuracy when the sounds were played while they were seeing the article transform; however, it had no impact when the sounds were played while they announced which item transform they had seen.

At long last, in a third trial with 40 members, Williams and partners played the sounds before the item transformations were shown. The objective here was to test whether sound information might impact visual insight by preparing individuals to focus closer on specific items. This was likewise found to meaningfully affect members’ item transformation determinations.

Taken together, these discoveries propose that sounds change visual discernment just when sound and visual information happen simultaneously, the scientists concluded.

“This course of perceiving objects on the planet feels easy and quick, yet truly it’s a computationally serious interaction,” Williams said. “To lighten a portion of this weight, your mind will assess data from different faculties.” Williams and partners might want to expand on these discoveries by investigating how sounds might impact our capacity to find objects, how visual information might impact our impression of sounds, and whether varying the media mix is an intrinsic or learned process.

More information: Jamal R. Williams et al, What You See Is What You Hear: Sounds Alter the Contents of Visual Perception, Psychological Science (2022). DOI: 10.1177/09567976221121348

Journal information: Psychological Science