According to research findings, captive lynxes have a higher level of virus exposure than wild lynxes. The Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) is an emerging zoonotic pathogen in Europe that affects humans, causing damage to the liver as well as other organs such as the kidney and the central nervous system. Animals are the primary source of HEV infection for humans in Europe.

A study by the Animal Health and Zoonosis Research Group (GISAZ) at the University of Cordoba, and the GC-26 Group at Cordoba’s Maimonides Biomedical Research Institute, together with other national and international institutions, and published in the journal Transboundary and Emerging Diseases, analyzed the exposure to Hepatitis E Virus in the Iberian lynx, an animal on which no studies of this type had been carried out, despite the fact that the virus is present in other species, such as pigs, wild boar, deer and horses, with which the Iberian lynx shares habitats in Spanish Mediterranean ecosystems. The results of the study confirmed that captive lynxes have a higher risk of exposure to Hepatitis E Virus than animals in the wild.

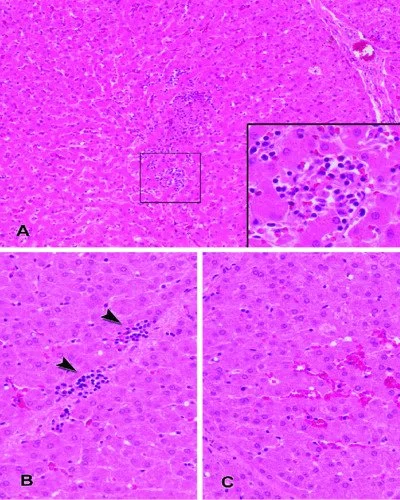

The researchers examined serum samples from 275 Iberian lynxes, as well as liver and feces samples from 176 others, to determine the prevalence and seroprevalence of the Hepatitis E Virus, i.e. the presence of active virus and antibodies after infection. Although only one animal was infected with the virus, the seroprevalence results differed depending on whether the lynx was in the wild or in captivity.

the exposure to Hepatitis E Virus in the Iberian lynx, an animal on which no studies of this type had been carried out, despite the fact that the virus is present in other species, such as pigs, wild boar, deer and horses, with which the Iberian lynx shares habitats in Spanish Mediterranean ecosystems.

Caballero Gómez

According to Javier Caballero Gómez, a researcher at the University of Cordoba’s Department of Animal Health and the Maimónides Biomedical Research Institute, “in captive populations, seroprevalence reached 33 percent of the lynxes studied, while in free-ranging populations, exposure to the virus was much lower: 7 percent.”

Consumption of products derived from infected animals is thought to be the primary route of transmission of Hepatitis E in humans, and has also been proposed for other animal species, including felines. Although more research is needed to confirm it, an initial hypothesis that the research team is considering about the difference in exposure between lynxes in the wild and in captivity, in addition to possible contact with other infected species, is the lynx’s diet, which primarily consists of rabbits.

While wild lynxes mainly consume wild rabbits, and previous studies carried out by this same group have shown that there is hardly any circulation of the Hepatitis E Virus in their populations, captive lynxes feed mainly on farm rabbits, and there are studies that have found virus circulation in these rabbits in Italy and France, although the presence of the virus in these animals in Spain has not yet been evaluated.

In terms of infection in other animals, this pathogen rarely causes symptoms or severe lesions in animal populations, and its presence is fleeting. In pigs, for example, it usually stays in the blood for one to two weeks and in the feces for no more than eight weeks. Nonetheless, in order to limit virus exposure in the Iberian lynx, it would be useful to understand how infection occurs, particularly in captive animals, where greater exposure has been observed. If the hypothesis that farm rabbit meat is the main route of infection in this subpopulation is confirmed, measures to prevent infection, such as feeding animals rabbits from farms that do not have the virus, could be implemented.

Finally, the study discovered the presence of genotype 3f of the hepatitis E virus in lynxes, which is the most common in infected people in Spain. However, as the research team points out, the presence of this genotype should not cause public concern because the Iberian lynx is not a food source for humans and contact with these species is rare. “It is true that in captivity centers there is some proximity with the animals or contact with feces, which could be contaminated, but the risk is very low,” Caballero Gómez says.