Breast cancer is a complicated disease with numerous risk factors such as genetic, hormonal, lifestyle, and environmental variables. While air pollution, notably fine particulate matter (PM2.5), has been linked to a variety of negative health impacts, including respiratory and cardiovascular illness, its significance in breast cancer is unclear.

Living in a location with high levels of particulate air pollution was linked to an increased incidence of breast cancer, according to researchers at the National Institutes of Health. The study, which was published in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute, is one of the largest yet conducted on the association between outdoor air pollution, specifically fine particulate matter, and breast cancer incidence. The research was done by scientists at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI), both part of NIH.

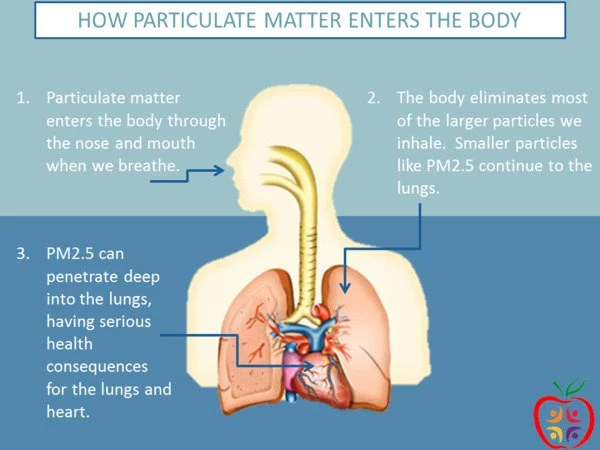

The researchers discovered that women who lived in locations with higher levels of particulate matter (PM2.5) near their homes before to joining in the trial had greater rates of breast cancer incidence than those who resided in areas with lower levels of PM2.5. Particulate matter is an airborne combination of solid particles and liquid droplets. It is produced by a variety of processes, including motor vehicle exhaust, combustion processes (e.g., oil, coal), wood smoke/vegetation burning, and industrial pollutants.

The particulate matter pollution measured in this study was 2.5 microns in diameter or smaller (PM2.5), meaning the particles are small enough to be inhaled deep into the lungs. The Environmental Protection Agency has a website known as Air Now where residents can enter their zip code and get the air quality information, including PM2.5 levels, for their area.

We observed an 8% increase in breast cancer incidence for living in areas with higher PM2.5 exposure. Although this is a relatively modest increase, these findings are significant given that air pollution is a ubiquitous exposure that impacts almost everyone. These findings add to a growing body of literature suggesting that air pollution is related to breast cancer.

Alexandra White

“We observed an 8% increase in breast cancer incidence for living in areas with higher PM2.5 exposure. Although this is a relatively modest increase, these findings are significant given that air pollution is a ubiquitous exposure that impacts almost everyone,” said Alexandra White, Ph.D., lead author and head of the Environment and Cancer Epidemiology Group at NIEHS. “These findings add to a growing body of literature suggesting that air pollution is related to breast cancer.”

The study used data from the NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study, which included over 500,000 men and women in six states (California, Florida, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Louisiana) and two urban regions (Atlanta and Detroit) between 1995 and 1996. The women in the cohort were, on average, 62 years old, and the majority classified as non-Hispanic white. They were monitored for almost 20 years, during which time 15,870 breast cancer cases were discovered.

Each participant’s annual average historical PM2.5 values were estimated by the researchers. Given the amount of time it takes for some malignancies to develop, they were particularly interested in air pollution exposures prior to enrolment in the trial. Most earlier research investigated breast cancer risk in connection to air pollution near the time of study enrollment and did not take into account previous exposures.

“The ability to consider historic air pollution levels is an important strength of this research,” said Rena Jones, Ph.D., the study’s senior author and main investigator. “It can take many years for breast cancer to develop and, in the past, air pollution levels tended to be higher, which may make previous exposure levels particularly relevant for cancer development.”

The researchers looked at how the association between air pollution and breast cancer differed depending on the type of tumor. They looked at estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) and -negative (ER-) cancers individually. They discovered that PM2.5 was linked to an increased risk of ER+ breast cancer but not ER- tumors. This implies that PM2.5 may have an effect on breast cancer via an underlying physiological mechanism of endocrine disturbance. ER+ tumors are the most common type of tumor found in women in the United States.

The study’s ability to investigate disparities in the association between air pollution and breast cancer across different study locations was limited, according to the authors. They suggest future work should explore how the regional differences in air pollution, including the various types of PM2.5 women that women are exposed to, could impact a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.