As the world faces the difficulties of present-day environmental change, a logical request is, among different targets, investigating how human social orders explore natural varieties at large. Researching the past gives important bits of knowledge into this.

In a new study that was published in the journal Quaternary Science Reviews, researchers from the ROOTS Cluster of Excellence at Kiel University and colleagues from Oslo, Troms, and Stavanger (Norway) presented an unprecedentedly extensive set of archaeological and environmental data that revealed connections between climate changes, population dynamics, and cultural changes in the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age (roughly 4100 to 1100 before the common era) in Northern Germany and Scandinavia today.

“In opposition to the thought that social orders were uninvolved beneficiaries of ecological movements, the review uncovers that these old networks created refined systems to explore and adjust to evolving conditions,” says Dr. Magdalena Bunbury, the review’s lead creator.

The review, which utilized a remarkably broad arrangement of archeological information, used carbon isotope investigation to detect hints of human activities inside the exploration region. Over the course of 17,000 years, more than 20,000 14C samples were collected by the authors. After unbending quality control, 6,268 remained significant for the review. “Utilizing numerous factual methodologies, we can remake whether populace numbers expanded or diminished during explicit ages,” makes sense to Dr. Bunbury.

“The study reveals that, contrary to the popular belief that societies were passive recipients of environmental changes, these ancient communities developed sophisticated strategies to navigate and adapt to changing conditions.”

Dr. Magdalena Bunbury, the study’s lead author.

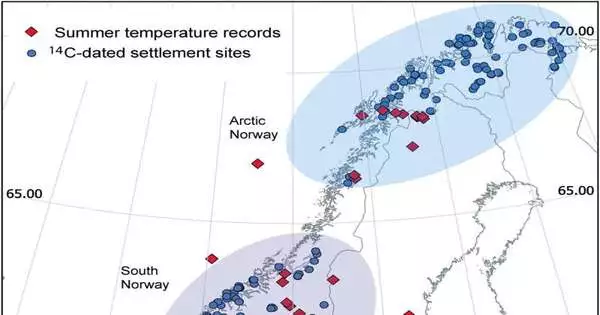

“We likewise examined 49 high-goal environment documents from somewhere in the range of 50 and 70 degrees north scope, empowering a nitty-gritty reproduction of natural circumstances in the review district somewhere in the range of 4100 and 1100 BCE,” adds co-creator Dr. Mara Weinelt from the ROOTS Group of Greatness, who started the review. Also, the group consolidated archeological data about in excess of 3,600 houses from almost 1,500 locales across a large portion of the review region.

The study’s findings emphasize the nuanced relationship between regional climate trends and local adaptations based on this extensive dataset. For instance, the effects of a significant warm period during the Holocene in Scandinavia between approximately 7050 and 2050 BCE varied according to latitude.

“In Southern Scandinavia, this hotter environment could have worked with the spread of horticulture in the mid-fourth thousand years BCE, harmonizing with a huge populace development,” says Dr. Bunbury, who explored as a postdoctoral individual at the ROOTS Group of Greatness until 2022 and is presently working at James Cook College in Cairns, Australia.

The beginning of a climate shift that varied in duration and timing across the study area’s latitudes and regions began with a cooling trend around 2250 BCE. Neolithic people groups in southern Norway, notwithstanding confronting cooling patterns, exhibited flexibility by proceeding to develop and getting comfortable with the locale.

In Denmark, people also built houses that could store harvests for longer periods of time and cultivate a wider variety of crops. These cycles can be deciphered as clear transformations to changing natural circumstances,” makes sense of co-creator Dr. Jutta Kneisel from Kiel College.

In the freezing fields of cold Norway, a particular methodology arose. Rather than drenching themselves in huge-scale cultivation, the networks went to rummaging—the social affair of food from nature—as their favored method for surviving. “As opposed to escalating their agrarian interests, the Icy Norwegian people group showed key sharpness by broadening their monetary exercises to alleviate gambles,” Dr. Bunbury further explains.

The concentrate further digs into the second thousand years BCE, uncovering sudden cooling periods and comparing decreases in population numbers. The corresponding data reveal simultaneous short-term population declines. Archeological discoveries propose breaks in exchange networks with Mainland Europe.

After these momentary cooling periods, the populace started to develop again from the center of the second thousand years and fostered a new, stable house structure.

“Climate change cannot account for all changes in human societies. Nonetheless, the information obviously shows huge connections between population improvement, home and monetary practices on the one hand, and environmental patterns on the other. Particularly the recuperation of population numbers after sudden cooling occasions in the second thousand years is an obvious sign of the flexibility or versatility of early social orders in Scandinavia to environmental fluctuation,” says Dr. Weinelt. Further examinations zeroing in on more modest areas could yield more experiences into the association among people and the climate.

More information: Magdalena Maria Elisabeth Bunbury et al, Understanding climate resilience in Scandinavia during the Neolithic and Early Bronze Age, Quaternary Science Reviews (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.108391