At the point when charged particles are shot through super slender layers of material, some of the time awesome miniature blasts happen, and in some cases the material remaining parts practically in salvageable shape. The explanations behind this have now been made sense of by scientists at the TU Wien.

It sounds a bit like an enchanted stunt: a few materials can be shot through with quick, electrically charged particles without displaying openings a short time later. What might be inconceivable at the perceptible level is permitted at the level of individual particles. Nonetheless, not all materials act similar in such circumstances — lately, unique examination bunches have led explores different avenues regarding altogether different outcomes.

It is now possible to find a definitive explanation for why some materials are punctured while others are not at the TU Wien (Vienna, Austria).This is fascinating, for instance, for the handling of slender layers, which should have tailor-made nanopores to trap, hold, or let through quite certain iotas or atoms there.

“There is now a wide variety of ultrathin materials with only one or a few atomic layers. Graphene, a substance composed of a single layer of carbon atoms, is probably the most well-known of them. However, research on alternative ultrathin materials, such as molybdenum disulfide, is being conducted around the world today.”

Prof. Christoph Lemell of the Institute of Theoretical Physics at TU Wien.

Superslender materials: graphene and its companions

“Today, there is an entire scope of ultrathin materials that comprise only one or a couple of nuclear layers,” says Prof. Christoph Lemell of the Organization of Hypothetical Material Science at TU Wien. “Likely the most popular of these is graphene, a material made of a solitary layer of carbon molecules.” In any case, research is additionally being finished on other ultrathin materials all over the planet today, for example, molybdenum disulfide.

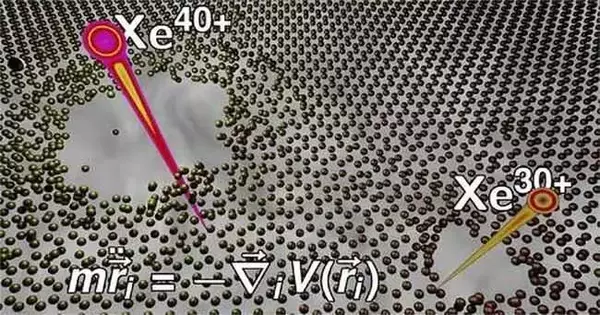

In Prof. Friedrich Aumayr’s exploration group at the Organization of Applied Physical Science at TU Wien, such materials are barraged with extremely exceptional shots—pprofoundly charged particles. They take iotas, commonly honorable gases like xenon, and strip them of an enormous number of electrons. This produces particles with 30 to 100 times the electrical charge.These particles are sped up and afterward hit the meager layer of material with high energy.

“This has completely different effects depending on the material,” says Anna Niggas, an exploratory physicist at the Organization of Applied Physical Science.”In some cases, the shot enters the material layer with no recognizable change in the material subsequently.” “At times the material layer around the effect site is likewise totally obliterated; various particles are ejected, and an opening with a width of a couple of nanometers is shaped.”

The speed of the electrons

These distinctions can be explained by the fact that the shot’s electric charge, rather than its energy, is primarily responsible for the openings. At the point when a particle with numerous positive charges stirs things up around the town layer, it draws in a bigger measure of electrons and takes them with it. This leaves a decidedly charged district in the material layer.

The impact is heavily dependent on how fast electrons can move in this material.”Graphene has an incredibly high electron versatility.” As a result, the positive charge in the neighborhood can be adjusted quickly.”Electrons just come in from somewhere else,” Christoph Lemell explains.

In different materials, such as molybdenum disulfide, the situation is unique:There, the electrons are slower; they can’t be provided in that frame of mind outside the effect site. Thus, a smaller than expected blast happens at the effect site: The decidedly charged particles, from which the shot has taken its electrons, repel one another; they fly away, and this makes a nano-sized pore.

“We have now had the option to foster a model that permits us to gauge very well in which circumstances openings are framed and in which they are not, and this relies upon the electron portability of the material and the charge condition of the shot,” says Alexander Sagar Grossek, the first creator of the distribution in the journal Nano Letters.

The model additionally makes sense of the astounding truth that the iotas taken out of the material move generally leisurely: the rapidity of the shot doesn’t make any difference to them; they are eliminated from the material by electrical shock only after the shot has previously gone through the material layer. Furthermore, in this cycle, not all the energy of the electric shock is moved to the faltered iotas—a huge piece of the energy is caught up in the excess material as vibrations or intensity.

Both the trials and the recreations were performed at TU Wien. The subsequent, more profound comprehension of nuclear surface cycles can be utilized, for instance, to explicitly outfit films with custom-made “nanopores.” For instance, one could fabricate a “sub-atomic sifter” or hold specific particles in a controlled way. There is even talk of using such materials to remove CO2 from the atmosphere. “Through our discoveries, we presently have exact command over the control of materials at the nanoscale.” “This gives an entirely different device for controlling ultrathin films in an exactly measurable manner, which is interesting,” says Alexander Sagar Grossek.

More information: Alexander Sagar Grossek et al, Model for Nanopore Formation in Two-Dimensional Materials by Impact of Highly Charged Ions, Nano Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.2c03894

Journal information: Nano Letters