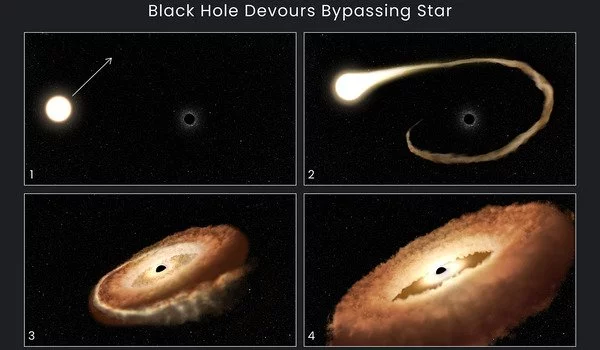

The Hubble Space Telescope has observed a black hole that is twisting a captured star into a donut shape. This is caused by the intense gravitational forces of the black hole, which cause the star to stretch out into a long, thin shape. This process, known as “spaghettification,” can ultimately lead to the star being consumed by the black hole. The observation of this process provides insight into the behavior of black holes and the effects of their gravity on nearby objects.

Black holes are gatherers rather than hunters. They wait for a hapless star to pass by. When a star gets close enough, the black hole’s gravitational pull violently rips it apart, sloppily devouring its gasses while emitting intense radiation.

Astronomers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope captured in detail a star’s final moments as it was devoured by a black hole. Tidal disruption events are what they’re called. The language, however, belies the complex, raw violence of a black hole encounter. There is a balance between the gravity of the black hole pulling in star material and radiation blowing material out. To put it another way, black holes are messy eaters. Astronomers are using Hubble to find out the details of what happens when a wayward star plunges into the gravitational abyss.

Hubble can’t photograph the AT2022dsb tidal event’s mayhem up close, since the munched-up star is nearly 300 million light-years away at the core of the galaxy ESO 583-G004. But astronomers used Hubble’s powerful ultraviolet sensitivity to study the light from the shredded star, which include hydrogen, carbon, and more. The spectroscopy provides forensic clues to the black hole homicide.

We’re looking somewhere near the edge of that donut. We’re witnessing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping across the surface and being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (three percent the speed of light).

Emily Maksym

Astronomers have detected approximately 100 tidal disruption events around black holes using various telescopes. NASA recently reported that several of its high-energy space observatories detected another black hole tidal disruption event on March 1, 2021, in another galaxy. Unlike Hubble observations, data was collected in X-ray light from an extremely hot corona surrounding the black hole that formed after the star had already been ripped apart.

“Given the observing time, however, there are still very few tidal events observed in ultraviolet light. This is extremely unfortunate because the ultraviolet spectra can provide a wealth of information” said Emily Engelthaler of the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian (CfA) in Cambridge, Massachusetts. “We’re excited because we can get these details about what the debris is doing. The tidal event can tell us a lot about a black hole.” Changes in the doomed star’s condition are taking place on the order of days or months.

For any given galaxy with a quiescent supermassive black hole at the center, it’s estimated that the stellar shredding happens only a few times in every 100,000 years.

This AT2022dsb stellar snacking event was first caught on March 1, 2022 by the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASAS-SN or “Assassin”), a network of ground-based telescopes that surveys the extragalactic sky roughly once a week for violent, variable, and transient events that are shaping our universe. This energetic collision was close enough to Earth and bright enough for the Hubble astronomers to do ultraviolet spectroscopy over a longer than normal period of time.

“These events are typically difficult to observe. When it’s really bright at the start of the disruption, you might get a few observations. Our program is unique in that it is designed to examine a few tidal events over the course of a year to see what happens “said CfA’s Peter Maksym. “We saw this early enough that we could observe it during the most intense stages of black hole accretion. The accretion rate gradually decreased to a trickle over time.”

The Hubble spectroscopic data are thought to be from a very bright, hot, donut-shaped area of gas that was once a star. This area, known as a torus, is the size of the solar system and is swirling around a black hole in the middle.

“We’re looking somewhere near the edge of that donut. We’re witnessing a stellar wind from the black hole sweeping across the surface and being projected towards us at speeds of 20 million miles per hour (three percent the speed of light)” Maksym explained. “We’re still wrapping our heads around the event. You shred the star, and then it has this material that is making its way into the black hole. So you have models where you think you know what’s going on, and then you have what you actually see. This is an exciting place for scientists to be: at the crossroads of the known and unknown.”