According to a new study, human-caused extinctions of the largest herbivores and carnivores are disrupting what appears to be a fundamental feature of past and present ecosystems. According to a new study, the U-shaped relationship between diet and size in modern land mammals could also stand for “universal,” as it spans at least 66 million years and a variety of vertebrate animal groups.

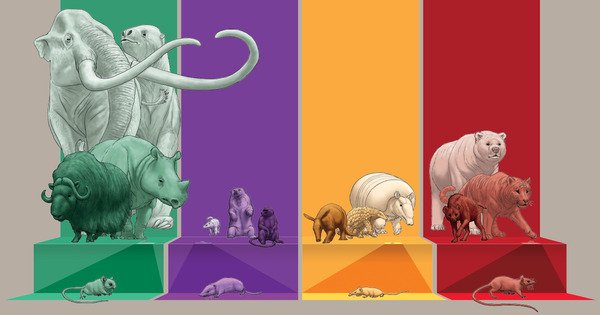

Ecologists have known for decades that graphing the diet-size relationship of terrestrial mammals yields a U-shaped curve when those mammals are aligned on a plant-to-protein gradient. As illustrated by that curve, the plant-eating herbivores on the far left and meat-eating carnivores on the far right tend to reach sizes much larger than those of the all-consuming omnivores and the invertebrate-feasting invertivores in the middle.

To date, however, almost no research has looked beyond mammals or the modern day for the pattern. Researchers from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln and institutions on four continents concluded in a new study that the pattern is ancient and applies to land-dwelling birds, reptiles, and even saltwater fishes.

However, the study also suggests that human-caused extinctions of the largest herbivores and carnivores are causing a disruption in what appears to be a fundamental feature of past and present ecosystems, with potentially unpredictable consequences.

“We’re not sure what’s going to happen, because this hasn’t happened before,” said Will Gearty, a postdoctoral researcher at Nebraska and co-author of the study, published in the journal Nature Ecology and Evolution. “But because the systems have been in what seems to be a very steady state for a very long time, it’s concerning what might happen when they leave that state.”

We’re not sure what’s going to happen, because this hasn’t happened before. But because the systems have been in what seems to be a very steady state for a very long time, it’s concerning what might happen when they leave that state.

Will Gearty

Size up, size down

According to Gearty, the intertwined influences of diet and size can be used to tell the evolutionary and ecological histories of animal species. The diet of a species determines its energy consumption, which drives growth and ultimately helps dictate its size. However, that size can limit the quality and quantity of food available to a species while also establishing thresholds for the quality and quantity required to survive.

“You can grow as big as your food allows,” Gearty explained. “At the same time, you’re usually big enough to catch and process your food. So there is an evolutionary interplay going on.”

Because herbivores’ plant-based diet is relatively low in nutrition, they frequently grow massive in order to cover more ground to forage more food – and to accommodate long, complex digestive tracts that extract maximum nutrients from it. Carnivores, on the other hand, must grow large enough to both keep up with and defeat herbivores. Though omnivores’ buffet-style menus usually keep their stomachs full, their high energy demands force them to focus on nuts, insects, and other small, energy-dense foods. While invertivores eat mostly protein-rich prey, their small size, combined with stiff competition from other invertivores, confines them to the smallest sizes of all.

The end result is a U-shaped distribution of average and maximum body size distributions in mammals. To assess the generalizability of that pattern in the modern era, the researchers gathered body-size data from 5,033 mammals, 8,991 birds, 7,356 reptiles, and 2,795 fishes.

Though the pattern was absent in marine mammals and seabirds, most likely due to the unique demands of living in water, it did emerge in the other vertebrate groups studied by the team: reptiles, saltwater fishes, and land-based birds. When analyzing land mammals, land birds, and saltwater fishes, the pattern held across various biomes — forests vs. grasslands vs. deserts, for example, or the tropical Atlantic Ocean vs. the temperate North Pacific.

“Showing that this exists across all these different groups does suggest that it is something fundamental about how vertebrates acquire energy, how they interact with one another, and how they coexist,” said co-author Kate Lyons, assistant professor of biological sciences at Nebraska. “We don’t know whether it’s necessary — there might be other ways of organizing vertebrate communities with respect to body size and diet — but it certainly is sufficient.”

But the researchers were also interested in learning how long the U-curve may have endured. So they analyzed fossil records from 5,427 mammal species, some of which date as far back as the

From 145 million to 100 million years ago, the Earth was in the Early Cretaceous Period. Lyons and colleagues first gathered the fossil data as part of a 2018 study on the extinction of large mammals caused by humans and their recent ancestors.

“To my knowledge, this is the most comprehensive study of the evolution of body size and, in particular, diet in mammals over time,” Gearty said.

It was discovered that the U-curve dates back at least 66 million years, when non-avian dinosaurs had just been wiped out and mammals had not yet evolved into the dominant animal class that they are today.

The shape of things to come

After cataloguing the U-present curve’s and past, Gearty, Lyons, and their colleagues turned their attention to its potential future. The team reported that the median sizes of herbivores and omnivores have decreased roughly 100-fold since the emergence of Neanderthals and Homo sapiens over the last few hundred thousand years, while carnivores have decreased by about 10 times in the same time period. As a result, the long-standing U-curve has begun to flatten, according to Gearty.

In that vein, the team predicts that multiple large and medium-sized mammals, including the tiger and Javan rhinoceros, which have only humans as predators, will become extinct within the next 200 years. According to the researchers, the predicted extinctions would only exacerbate the disruption of the U-curve, especially to the extent that the loss of large herbivores could trigger or accelerate the loss of large carnivores that prey on them.