The Black Death, a plague outbreak, arrived in the Mediterranean ports of southern Europe in 1347 and swept across Europe in three years. The primary method of combating plague was to isolate known or suspected cases, as well as individuals who had come into contact with them. The period of isolation was initially set at 14 days and gradually increased to 40 days.

A genetic variant that appears to have boosted medieval Europeans’ ability to survive the Black Death centuries ago may have contributed – albeit in a minor way – to an inflammatory disease that people are currently suffering from.

Researchers used DNA from centuries-old remains to decipher the imprints that bubonic plague left on European immune systems during the Black Death. Researchers report in Nature that this devastating wave of disease tended to spare those who possessed a variant of a gene known as ERAP2, causing it to become more common. Scientists already know that that variant increases the chances of developing Crohn’s disease, a condition in which erroneous inflammation harms the digestive system.

According to Mihai Netea, an infectious diseases specialist at Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, Netherlands, who was not involved in the study, the findings show “how these studies on ancient DNA can actually help actually understand diseases even now.” “And the trade-off is also obvious.”

A genetic analysis seeking traces of historical disease in modern Europeans and a study of DNA from the remains of 16th century German plague victims both turned up what appear to be protective changes against the plague that, like the ERAP2 variant, are linked with inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

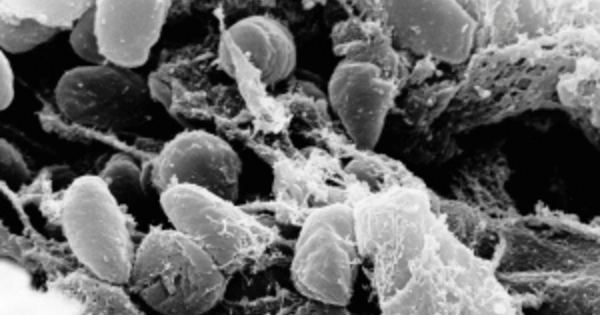

Bubonic plague, caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, once killed 60% of those infected. It caused successive waves of misery in the ancient world, the most devastating of which was the Black Death, often dated from 1346 to 1350, an episode thought to have wiped out at least 25 million people — roughly a third or more of Europe’s population.

Pathogens such as Y. pestis have shaped the evolution of the human immune system by sparing individuals whose immune systems exhibit certain characteristics. Studies are being conducted to determine how the massive eradication of the plague altered Europeans’ immune-related genetics.

In this most recent study, population geneticist Luis Barreiro of the University of Chicago and colleagues collected DNA samples from the remains of 516 people who died between 1000 and 1800 in London and Denmark, including those buried during the Black Death. The researchers looked for immune-related genes and areas associated with autoimmune and inflammatory diseases in stretches of DNA.

Within those regions, the researchers identified four locations on chromosomes where they saw strong evidence of genetic changes that appeared to have been driven by the Black Death. In follow-up work, one change stood out: an increase in the frequency of a variant of ERAP2. When infected with Y. pestis, immune cells from people with this version of ERAP2 more effectively killed the bacteria than cells lacking the variant. Studies of modern populations have linked that same variant to Crohn’s disease.

While the researchers calculate that the ERAP2 variant improved the odds of surviving the Black Death by as much as 40 percent, it only slightly increases the risk for Crohn’s disease. For complex disorders like Crohn’s, “you require probably hundreds, sometimes thousands of genetic variants to actually increase your risk in a significant manner,” Barreiro says.

For some time now, researchers in the field have theorized that adaptations that helped our ancestors fortify their immune systems against infectious diseases can contribute to excessive, damaging immune activity. Earlier studies of plague offer support for this idea. A genetic analysis seeking traces of historical disease in modern Europeans and a study of DNA from the remains of 16th century German plague victims both turned up what appear to be protective changes against the plague that, like the ERAP2 variant, are linked with inflammatory and autoimmune conditions.

Likewise, this latest discovery suggests that genetic changes that have amped up the human immune response in the past, empowering it to better fight off ancient infections, can come at a cost. “If you turn the heat too much, that leads to disease,” Barreiro says.