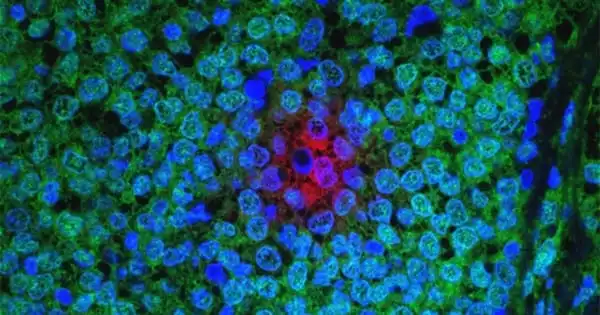

Breast cancer that has spread to another part of the body, most commonly the liver, brain, bones, or lungs, is known as metastatic breast cancer (also known as stage IV). Cancer cells can spread from the original tumor in the breast to other parts of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system, which is a large network of nodes and vessels that works to remove bacteria, viruses, and cellular waste products.

A multi-institutional team of researchers led by Baylor College of Medicine scientists has discovered a genetic signature that can identify drivers of poor outcomes in advanced estrogen-receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, potentially leading to personalized treatment for patients.

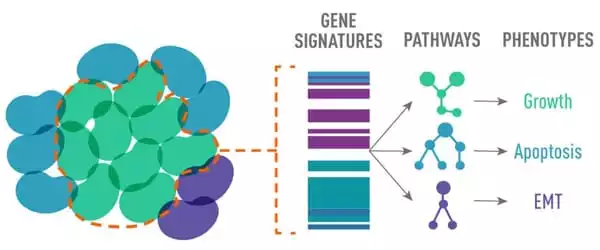

The 24-gene signature detects the presence of ER gene mutations and translocations, which give the tumor the ability to grow independently of estrogen and thus make it resistant to current therapies aimed at disrupting estrogen-fueled cancer growth. The findings, published in Cancer Research, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, offer a new strategy for refining breast cancer diagnosis, which could aid in the selection of tumor-specific treatments.

We discovered a genetic signature that can identify drivers of poor outcomes in advanced estrogen-receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer, potentially leading to personalized treatment for patients. One of the most common ways ER+ breast cancer cells evade treatment is by producing mutant ERs that are no longer recognized and targeted by ER-targeting cancer drugs.

Xuxu Gou.

Disrupting the estrogen-ER interaction is a key therapeutic approach. Drugs such as tamoxifen and fulvestrant target the ER this way, but tumor cells learn to evade this attack and become resistant to these drugs.

“One of the most common ways ER+ breast cancer cells evade treatment is by producing mutant ERs that are no longer recognized and targeted by ER-targeting cancer drugs,” explained first author Xuxu Gou, a graduate student in the Ellis lab.

The researchers have been researching ESR1 gene translocations, which occur when the ER gene swaps a portion of its sequence with genetic information from another gene. ER gene translocations result in chimeric ER proteins, which contain only half of the ER protein and the other half from a different protein. Some of the ER chimeras are extreme versions of mutant ERs in which the drug-binding region, which is also the region to which estrogen binds, has been completely replaced with a region derived from another protein, to which neither the drug nor estrogen can bind. In the absence of hormones, these ER chimeras activate cancer.

“Not all ER translocations were active; some drive metastasis and treatment resistance, while others do not,” Gou explained. “We developed a diagnostic genetic signature that detects the presence of an active ESR1 chimeric protein to determine whether any particular ESR1 translocation can promote disease progression.”

The team used genomics and transcriptomics to annotate 20 mouse models of ER+ patient-derived tumors that demonstrated varying degrees of reliance on estrogen for growth, with funding from the National Cancer Institute’s PDXnet program. A 24-gene signature detected the presence of an active ESR1 fusion in this data set, but also common point mutations in ESR1. These findings were confirmed in a human metastatic breast cancer cohort. As a result, the team dubbed their 24 gene signature the MOTERA score, which stands for “Mutant or translocated Estrogen Receptor Alpha.”

The findings are significant in the field of precision medicine because they can provide specific details about the tumor that can help doctors choose more effective treatments.

“In the future, cancer cells from a patient could be analyzed, and if the MOTERA score indicates the presence of an ER mutation or translocation, the tumor cells could be further studied to determine what type of ER mutant or translocation is present. This would aid in the selection of a customized, optimal treatment” Dr. Charles E. Foulds, assistant professor at Baylor’s Lester and Sue Smith Breast Center, is one of the study’s co-authors.

Being diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer can be a terrifying experience. You may experience feelings of rage, fear, stress, outrage, and depression. Some people may have doubts about their treatments or be angry at their doctors or themselves for not being able to beat the disease. Others may take a matter-of-fact approach to the diagnosis of metastatic breast cancer. There is no right or wrong way to accept the diagnosis. You must do and feel what is best for you and your circumstances.

It is important to remember that metastatic disease is NOT hopeless. Many people with this stage of breast cancer live long and productive lives. There are numerous treatment options for metastatic breast cancer, and new medications are being tested on a daily basis. While being treated for metastatic breast cancer, an increasing number of people are living life to the fullest.