Understudies now and again pull a dusk ’til dawn affair to get ready for a test. Notwithstanding, research has shown that lack of sleep is terrible for your memory. Presently, College of Groningen neuroscientist Robbert Havekes found that what you realize while being sleepless isn’t really lost; it is only challenging to review.

Along with his group, he has figured out how to make this “covered up information” available again in the wake of examining while restless, utilizing optogenetic approaches, and the human-supported asthma drug roflumilast. These discoveries were distributed in the journal Current Science.

Havekes, academic partner of Neuroscience of Memory and Rest at the College of Groningen, the Netherlands, and his group have broadly concentrated on what lack of sleep means for memory processes. “We recently centered around tracking down ways of supporting memory processes during a lack of sleep episode,” says Havekes. Be that as it may, in his most recent review, his group analyzed whether amnesia because of a lack of sleep was an immediate consequence of data misfortune or only brought about by hardships in recovering data.

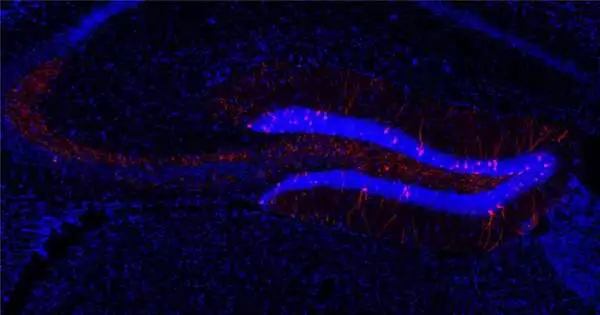

“We used this strategy to neurons in the hippocampus, the part of the brain where spatial information and factual knowledge are stored, in our sleep deprivation investigations.”

Havekes, associate professor of Neuroscience of Memory and Sleep

“Lack of sleep subverts memory processes, yet every understudy realizes that a response that escaped them during the test could spring up hours later.” “All things considered, the data was, in fact, stored in the mind, but it was only difficult to recover.”

Neurons in the hippocampus

To resolve this inquiry, Havekes and his group utilized an optogenetic approach: utilizing hereditary strategies, they caused a light-delicate protein (channelrhodopsin) to be created specifically in neurons that are enacted during a growth opportunity. This made it conceivable to review a particular encounter by focusing light on these cells. “In our lack of sleep studies, we applied this way to deal with neurons in the hippocampus, the region in the cerebrum where spatial data and verifiable information are stored,” says Havekes.

In the first place, the hereditarily designed mice were given a spatial learning task in which they needed to get familiar with the area of individual items, a cycle that vigorously depends on neurons in the hippocampus. The mice then needed to play out this equivalent undertaking days after the fact, yet this time with one item moved to a clever area. The mice who were denied rest for a few hours before the main meeting failed to notice this spatial change, implying that they don’t remember the first item areas.

“Nonetheless, when we once again introduced them to the errand in the wake of reactivating the hippocampal neurons that at first put away this data with light, they did effectively recollect the first areas,” says Havekes. “This shows that the data was put away in the hippocampus during a lack of sleep yet couldn’t be recovered without the excitement.”

Memory issues

The atomic pathway activated during reactivation is also identified by the medication roflumilast, which is used by patients with asthma or COPD.

According to Haskes, “When we gave mice that were prepared while being sleepless roflumilast not long before the subsequent test, they recollected, precisely as occurred with the immediate excitement of the neurons.” As roflumilast is now clinically endorsed for use in people and is known to enter the cerebrum, these discoveries open up roads to test whether reestablishing admittance to “lost” memories in humans can be applied.

The disclosure that more data is available in the mind than we recently expected and that these “covered up” recollections can be made open once more—iin mice—oopens up a wide range of energizing prospects.

“It very well may be feasible to animate the memory availability in individuals with age-prompted memory issues or beginning-phase Alzheimer’s illness with roflumilast,” says Havekes. “Also, perhaps we could reactivate explicit memories to make them forever retrievable once more, as we effectively did in mice.”

In the event that a subject’s neurons are invigorated with the medication while they attempt to “remember” a memory or reexamine data for a test, this data may be reconsolidated all the more immovably in the mind. “Until further notice, this is all theory, obviously; however, the truth will come out at some point.”

Currently, Havekes isn’t directly associated with such human examinations. “My advantage lies in disentangling the sub-atomic systems that underpin such a large number of cycles,” he explains. “What gains in experiences are available or out of reach?” How does Roflumilast reestablish access to these “covered up” memories? As consistently with science, by resolving one inquiry you get many new inquiries for nothing.”

More information: Youri G. Bolsius et al, Recovering object-location memories after sleep deprivation-induced amnesia, Current Biology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2022.12.006