The intense actual sickness portraying narcotic withdrawal is sufficiently intense to get through even with full family, local area, and clinical help, so it is a ruthless and in some cases lethal incongruity that one of withdrawal’s notable side effects is outrageous social revulsion.

“Self-segregation can make dependent individuals exit recovery programs, get into clashes, and pull away from family and other socially encouraging groups of people that could end up being useful to them to stay abstinent,” says Stanford psychiatry teacher Keith Humphreys, Ph.D., a worldwide master on compulsion treatment and public approach.

“Self-isolation can drive addicted persons to drop out of rehabilitation programs, get into fights, and withdraw from family and other social support networks that could help them stay abstinent,”

Stanford psychiatry professor Keith Humphreys, Ph.D., an international expert on addiction treatment and public policy.

New exploration by the lab of Stanford neuroscientist Robert Malenka, MD, Ph.D., has recognized a critical sub-atomic connection between narcotic withdrawal and social revulsion in the cerebrums of mice, proposing the possibility to assist people in recuperation from narcotic fixation reconnect with their socially encouraging groups of people.

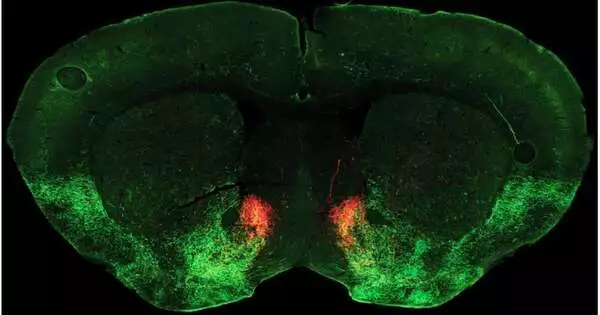

The review focuses on a vital job for the neuromodulator serotonin in turning friendliness on and off. According to Malenka, ordinarily, friendliness relies upon the arrival of serotonin in a space somewhere down in the cerebrum called the core accumbens, which by and large assumes a key role in connecting ways of behaving to inspiration and reward. In their new review, distributed October 5, 2022, in the journal Neuron, the analysts found how narcotic withdrawal reduces the stock of serotonin in this locale, decisively lessening amiability.

Malenka’s group based the study on a mouse model of narcotic withdrawal. The specialists gave increasing portions of morphine to the mice until the rodents were dependent, and then unexpectedly cut off the medication. They then tried the mice for friendliness.

“We estimated how long a mouse needs to spend spending time with a little pal. “It’s actually that basic,” says Malenka, the Nancy Pritzker Teacher of Psychiatry and Social Sciences and representative overseer of the Wu Tsai Neurosciences Organization. “During extended withdrawal from narcotics, each and every mouse in the review had extreme friendliness deficiencies.”

Malenka and his group had recently reported areas of strength for each other among friendliness and serotonin discharge in the core accumbens. In 2018, his gathering showed that decreased serotonin in the core accumbens could represent social shortages in a mouse model of chemical imbalance. Reestablishing serotonin discharge generally restored common degrees of rat amiability. After a year, they tracked down those enormous increases in serotonin in a similar mind locale, which “makes sense of the extraordinary favorable social impacts of MDMA,” Malenka says. “We suspect exactly the same thing is happening in people.”

These prior examinations drove Malenka and his associates to contemplate whether something almost identical was happening during withdrawal from narcotics. “Maybe, similar to the chemical imbalance mouse model, subjects aren’t getting the typical arrival of serotonin that is expected for supportive, versatile, non-forceful cooperationheso they become socially avoidant and cantankerous,” he says.

Malenka Lab postdoctoral researcher Matthew Pomrenze, who drove the group’s recently distributed study, made the association that a specific kind of narcotic receptor particle is known to lessen serotonin discharge inside the core accumbens. This receptor subtype, called a kappa receptor, had been connected to pressure, melancholy, and an asocial way of behaving, yet precisely what it meant for friendliness was obscure.

Pomrenze and partners performed nitty-gritty trials that uncovered that during narcotic withdrawal, a neuropeptide particle called dynorphin is delivered in the core accumbens, where it enacts kappa receptors and blocks serotonin discharge.

“We thought perhaps this is the thing that is causing the asocial behavior we find in withdrawal,” Malenka says. “All in all, we asked: assuming that we gave the creatures a medication that hinders this kappa receptor and reestablishes serotonin discharge, might it at some point likewise restore typical degrees of friendliness?”

To make the examination all the more clinically important, Malenka’s group utilized a kappa receptor blocker called aticaprant, which is now being tried for the treatment of certain subtypes of sadness in people. At the point when Malenka’s group gave the medication to their removed, dependent mice, “it totally turned around their amenability deficiencies,” says Malenka.

Accomplishing something almost identical for people could significantly affect the narcotic pestilence, says Humphreys, who co-coordinates the NeuroChoice Drive with Malenka and brain research teacher Brian Knutsen but was not engaged with the ebb and flow study.

In the event that narcotic dependent individuals going through withdrawal moved in the direction of wellsprings of help as opposed to away from them, a lot more could effectively weather the distresses of withdrawal and arrive at recovery with the assistance of companions, family, their PCPs, and projects, he says.

“Withdrawal is common in many cases when a specialist says, “You don’t need to live this way.” “We have phenomenal medicines that I’d be glad to associate you with.” Or when somebody the dependent individual knows says, “I was dependent on heroin for quite a long time, and I’m not utilizing any longer.” I’d be glad to take you to my Opiates Unknown gathering. “Yet in the event that the individual in withdrawal is keeping away from every single social communication, none of those possibly life-saving mediations can happen,” says Humphreys.

“This is precisely what NeuroChoice was intended to do,” says Humphreys. “To investigate across levels, from the cell to the person, to the gathering, to strategy,” Furthermore, from creatures to people.”

However, creating medications to assist with dependence is notoriously troublesome, Malenka warns. For a certain something, drug organizations don’t harvest enormous benefits from such medications. “Thus, the objective of our sort of work,” Malenka expresses, “is to persuade those in the human clinical exploration world to say, “Hello, this is functioning admirably in mice; I ought to attempt it in a clinical report.”

The component uncovered by Malenka’s group’s review will give whoever might do that a brilliant early advantage.

More information: Matthew B. Pomrenze et al, Modulation of 5-HT release by dynorphin mediates social deficits during opioid withdrawal, Neuron (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.09.024

Journal information: Neuron