a parent’s consoling touch a companion’s warm embrace A darling’s tempting hug These are among the material delights in our lives.

Currently, researchers at Columbia University’s Zuckerman Foundation and two collaborator organizations report previously unknown beginning stages in the neurobiological pathways underlying pleasurable, sexual, and generally rewarding social touch.In their mouse studies, they interestingly coaxed out a full pathway that starts with neurons in the skin that respond to delicate stroking and runs all the way to the joy centers of the mind. This exploration was distributed today in Cell.

The discoveries likewise highlight contact-based treatments for easing tension, stress, and gloom, the analysts said. Furthermore, such treatments may hold a guarantee for those with mental imbalance and other circumstances that can make a delicate touch disastrous.

“This task had high-risk/high-reward written all over it,” said Ishmail Abdus-Saboor, Ph.D., a key examiner at Columbia’s Zuckerman Foundation and a contributing author on the paper.”We recently continued to follow the information to where it took us.”

“We weren’t sure if this depiction of social contact was accurate. We wanted to see if there were tactile neurons that were specifically tuned for pleasant contact.”

Dr. Abdus-Saboor, who is also an assistant professor of biological sciences at Columbia.

Researchers have long realized the skin highlights material tactile cells—key parts of the fringe sensory system that empower us to observe various surfaces and temperatures, as well as assortments of pleasurable and agonizing mechanical boosts.

“We didn’t know this image of social touch was very correct,” said Dr. Abdus-Saboor, who is likewise an associate teacher of organic sciences at Columbia. “We set off to test whether there may be material neurons explicitly tuned for remunerating contact.”

Caltech scientists had hinted at this possibility when they focused on a class of tactile cells and named them Mrgprb4 cells after a receptor in their films.The researchers viewed these cells as receptive to light strokes.

The new examination in Cell is the culmination of a four-year cooperative effort that included almost 20 researchers (12 from the Abdus-Saboor lab, including the main creator) from three foundations to look undeniably more carefully at these cells.

Key to the review was a strong method called optogenetics, in which individual cell types are designed so they can be enacted when scientists focus explicit shades of light onto them. The method is particularly appropriate for coaxing out the elements of explicit populations of cells.

The analysts started their investigation in the fall of 2018 at the College of Pennsylvania, when Dr. Abdus-Saboor was an employee there concentrating on the neuroscience of torment. That is when then-graduate student Leah Elias and later lab expert William Cultivate (now a Columbia graduate student in the Neurobiology and Behavior program and first author on the Cell paper) mentioned an unexpected fact.

“We saw that by enacting this understudied populace of material tactile cells in the mouse’s back, the creatures would bring down their backs and take on this stance of dorsiflexion,” said Dr. Elias. In the realm of rodents, such a stance is a vital mark of sexual receptivity, which typically requires the actual consideration of an admirer mouse.

“It was odd.” “We didn’t have any idea what to think about it,” said Dr. Elias, presently a postdoctoral individual at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

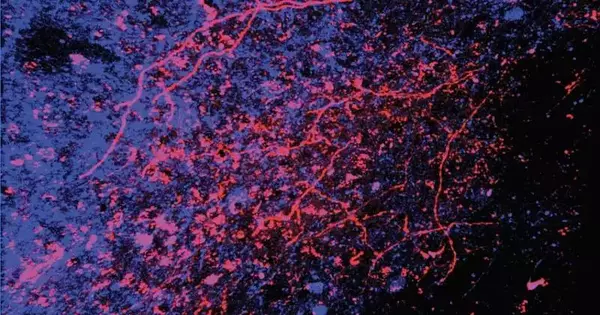

At the core of this charming lead was a line of mice. The group had been hereditarily designed so the creatures’ Mrgprb4 contact touchy cells would fire when enlightened with blue light. These sorts of touch cells had not recently been connected to a particular social way of behaving, yet when Dr. Elias and Encourage enacted these cells by focusing blue light on the mice, the pair could barely accept the dorsiflexion reactions they were seeing.

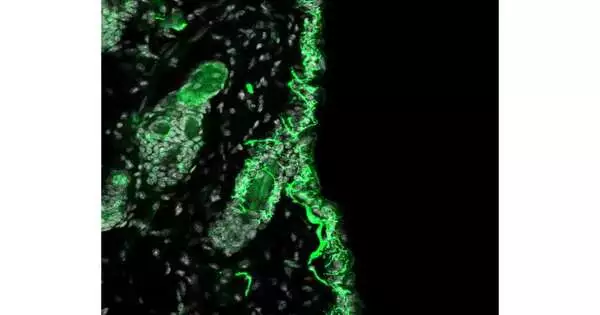

The fluorescent-green elements in this micrograph of the bushy skin of a mouse’s back uncover the presence of material tactile cells in the Mrgprb4 cell heredity.

Quick video information about how to behave was obvious. Also, later, the examination group, driven by then-graduate understudy Melanie Schaffler, noticed these equivalent mice willfully going to a similar spot in the exploration chamber where the creatures recently had been enlightened. That meant the creatures had completed the termination of Mrgprb4 tactile cells in their backs.

“This was the main reported model that a particular way of behaving may be created or upheld by these Mrgprb4 neurons,” Dr. Abdus-Saboor said.

While the dorsiflexion was entrancing and pointed towards a likely job for these phones in identifying sexual touch, the scientists required direct proof that they interfered with touch during normal social experiences. However, the pandemic mediated and slowed the pace of examination.It turned out to be so hard to push the exploration ahead that by the middle of 2020, the group thought about dropping the task altogether.

Almost too late, nonetheless, Dr. Elias, working with Isabella Succi, then an expert in the lab at Penn (and currently a graduate undergrad at Columbia in the Natural Sciences program), led a vital trial. Utilizing hereditary methods, they killed the Mrgprb4 cells. This empowered the researchers to check whether the shortfall of these cells in touch hardware impacted the mice’s sexual reaction to material feeling.

“The sexual receptivity recently dove,” Dr. Elias said. “We quickly realized that these cells were crucial for social touch in everyday experiences.”

As new as this finding was, it prompted a compelling yet overwhelming research question: how do these peripheral cells connect to downstream brain hardware via the spinal cord and then further into the mind?

Addressing this inquiry, Dr. Abdus-Saboor noted that it required methods beyond the lab’s comfort zone, which was in the fringe sensory system. Toward this end, Dr. Elias communicated an energy for the lab to embrace fiber photometry, a method that would permit them to see reward neurons in the mind “light up” in response to pleasurable boosts. Dr. Elias was able to demonstrate that enacting Mrgprb4 cells did indeed cause neurons to fire in the core accumbens, one of the mind’s recognized award places, over the next few months, thanks to critical assistance from Succi.

Yet a basic inquiry remained: how did this flag get from the skin to the mind?

As the developing group took on this diverse exploration in 2020, a Harvard-driven concentration revealed a telling piece of the pleasurable touch puzzle. In their investigations of touch-involved spinal rope cells, assigned as GPR83 cells, this examination bunch followed neuron-to-neuron joins in the two headings: midway into the brainstem and incidentally to the very class of Mrgprb4 cells that Dr. Abdus-Saboor’s group had displayed to identify and hand-off remunerating contact boosts.

“That gave us the idea that these GPR83 neurons are probably a pathway connecting the skin to the mind,” said Dr. Abdus-Saboor.

With extra tests in a joint effort with the Rutgers College lab of Victoria Abraira, Ph.D., the group figured out how to follow the skin-to-mind hardware of touch further and in more detail than had been accomplished beforehand. One significant finding is that the brainstem neurons the Harvard-Davis group examined connected to yet more profound areas in the mind, the ventral tegmental region as well as the core accumbens. That was an important association with notice because both mind regions had previously been linked to the experience of remuneration and joy.

Dr. Abdus-Saboor brings up the fact that individuals have tangible skin cells, called C-material afferents, which have some similarity with the Mrgprb4 cells in mice. People likewise have spinal line and mind neurons that relate to the touch hardware that Dr. Abdus-Saboor’s group and neuroscientists have been revealing. These likenesses open the way to expected biomedical applications, Dr. Elias said. It could become conceivable, for instance, to foster incidentally designated methods for treating pressure, tension, or gloom, whether through touch treatments or even clever medications applied straight to the skin.

“A significant side effect for some people with mental illness is that they can function without being contacted,” Dr. Abdus-Saboor added.”This makes one wonder whether the pathway we’ve recognized could be changed so individuals can profit from contact that ought to be remunerating instead of aversive.”

“The pandemic made us all acutely aware of how damaging a lack of social and actual contact can be,” Dr. Elias said. “I ponder the cognitive deterioration of the elderly in nursing homes who could never have common contact with guests. I ponder how actual contact among guardians and their babies and small kids is vital for a legitimate mental and social turn of events. We don’t yet comprehend how these sorts of touch convey their advantages, whether intensely pleasurable or advancing long haul mental prosperity. That is the reason this work is so fundamental.

More information: Ishmail Abdus-Saboor, Touch neurons underlying dopaminergic pleasurable touch and sexual receptivity, Cell (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.12.034. www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(22)01577-X