The actual cerebrum is a major impediment to treating brain disease, not the malignant growth.

The blood-mind boundary is a significant part of the cerebrum’s veins that prevents harm, infections, and microbes in the blood from penetrating the mind—yet it accidentally impedes most helpful substances.

Nanoparticles, centered ultrasound, smart science, and other creative thoughts are being attempted to beat the boundary and convey medicines to the mind. Presently, neurosurgeons at Columbia College and New York-Presbyterian are adopting a more straightforward strategy: a completely implantable siphon that constantly conveys chemotherapy through a cylinder embedded directly into the mind.

Another review, the first to test the implantable siphon framework in patients with mind disease, shows that the clever methodology really kills cerebrum growth cells and offers a protected method for treating patients with mind disease. Results from the review, a stage 1 preliminary study including five patients with repetitive glioblastoma, were distributed in the November issue of The Lancet Oncology.

“This new method has the potential to alter treatment for individuals with brain cancer, where the outlook for survival remains very dismal. However, more testing in patients with earlier-stage tumors and with different forms of chemotherapy is required.”

Jeffrey Bruce, MD, the Edgar M. Housepian Professor of Neurological Surgery Research

“This new methodology may change therapy for patients with cerebrum disease, where the outlook for endurance remains poor,” says Jeffrey Bruce, MD, the Edgar M. Housepian Teacher of Neurological Medical Procedure Exploration at Columbia College Vagelos School of Doctors and Specialists, and a neurosurgeon at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia College Irving Cli

The disease of the mind is impervious to treatment.

Patients with brain disease are first treated with a medical procedure to eliminate however much growth could be expected, followed by radiation and chemotherapy.

In principle, specialists could give patients higher dosages of chemotherapy—tthrough pills or intravenously—tto beat the blood-mind boundary and get more chemo into the cerebrum. Yet, at higher dosages, the medications cause too many side effects in different parts of the body, and patients can’t endure them.

As a result, the amount of chemotherapy that can be safely administered to patients with brain tumors is constantly limited.

“The cancers definitely recover,” says Bruce, who is likewise head of the Bartoli Mind Growth Exploration Lab at Columbia College’s Vagelos School of Doctors and Specialists. “Also, when they recover, there’s no demonstrated treatment for them.”

The middle endurance level for patients who go through treatment for glioblastoma is a little more than a year. When patients’ growths return, their guess is normally about four or five months.

A new framework penetrates the mind’s boundary.

Throughout the past 10 years, Bruce and his group have been dealing with a compressed siphon to sidestep the blood-mind boundary and direct chemotherapy to the region of the cerebrum where the cancer is found.

Yet, early models, which incorporated an outer siphon joined to a catheter embedded through the skull, permitted just a solitary treatment restricted to a couple of days prior to risking disease. Patients likewise needed to stay in the clinic while attached to the siphon.

To overcome this limit, Bruce’s group planned another model that has no outer parts and can be left set up for however long is required. A little siphon is precisely embedded into the midsection and associated with a slim, adaptable catheter strung under the skin. Stereotactic imaging guides the careful position of a catheter exactly in the space of the mind where the growth and any leftover disease cells are found.

“Assuming you siphon in the medication gradually, in a real sense, at a few drops every 60 minutes, it enters the brain tissue,” says Bruce, who first tried the strategy widely quite a while ago. “The medication focus that winds up in the mind is 1,000 times more prominent than anything you are probably going to get with intravenous or oral conveyance.”

Comparable implantable siphons are available to deliver torment drugs to the spinal line and can remain in place for a long time.The siphon can be topped off or purged with a needle. Remote innovation is utilized to turn the siphon on and off and control the stream rate, guaranteeing that the medication leaks in slowly and soaks the cancer without spilling out around the catheter.

“Most medications would be more viable if you gave them on a long-term basis without secondary effects,” Bruce says. “The siphon can remain set up for an extensive stretch of time, so we can give higher dosages of chemotherapy straight to the mind without causing the secondary effects that we get with oral or intravenous chemotherapy.”

A study demonstrates the safety and feasibility of implantable siphons.

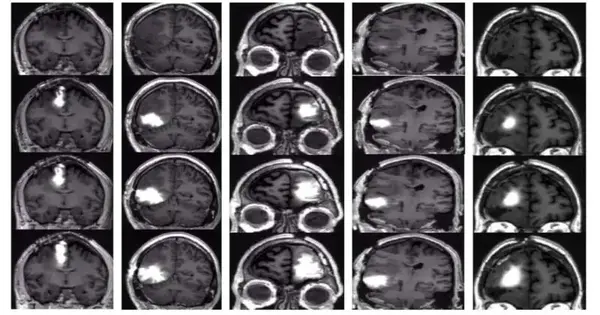

In the new review, the siphons were embedded in patients with repetitive glioblastoma and loaded up with topotecan, a chemotherapy drug used to treat cellular breakdown in the lungs, and gadolinium, a specialist to follow the dispersion of the medication. (Past examinations in Bruce’s lab proposed that nearby conveyance of topotecan, which targets effectively isolating cells, might be more viable than current treatments for glioblastoma.)

The patients had four medicines throughout one month; every week, the siphons were turned on for two days and off for five days. Patients approached their typical schedules at home while therapy proceeded, trickle by drip.

“The patients were strolling, talking, eating, and doing their typical everyday exercises in general.” “They wouldn’t know regardless of whether the siphon was on,” Bruce says.

None of the patients had serious neurological confusion. Also, X-ray checks showed that chemotherapy had soaked the region in and around the cancer.

However, the quantity of patients was too small to identify a general endurance benefit, but a novel examination of pre-therapy and post-therapy biopsies managed by Peter Canoll, MD, Ph.D., teacher of pathology and cell science at Columbia, head of neuropathology at NewYork-Presbyterian/Columbia College Irving Clinical Center, and a senior creator of the review, showed that the chemotherapy was working: The number of cancer cells that could be effectively isolated decreased significantly, while normal synapses were unaffected.

Patient-centered way to deal with treating mental diseases

New studies are being conducted to determine whether the treatment is also safe for patients with recently diagnosed glioblastoma and whether it can improve endurance.

“A ton has previously ended up making the growth harder to treat when starting treatments fizzle, so we feel that the siphon will work far better with the recently analyzed patients,” Bruce says. “This approach would enable us to change the treatment over the long haul and consider utilizing different sorts of chemotherapy that wouldn’t be viable whenever given fundamentally yet might be significantly more powerful when conveyed directly to the mind.”

More information: Eleonora F Spinazzi et al, Chronic convection-enhanced delivery of topotecan for patients with recurrent glioblastoma: a first-in-patient, single-centre, single-arm, phase 1b trial, The Lancet Oncology (2022). DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00599-X

Journal information: Lancet Oncology