For good reason, green is a color that is almost universally associated with plants. The green pigment chlorophyll is necessary for plants to generate food; however, what happens if they don’t have enough of it? New research reveals the complex, interdependent nutrient responses that underpin chlorosis, a potentially fatal low-chlorophyll state characterized by an anemic, yellow appearance. It has the potential to usher in more environmentally friendly agricultural practices, such as the use of less fertilizer and fewer water resources.

For good reason, green is a color that is almost universally associated with plants. The green pigment chlorophyll is necessary for plants to generate food; however, what happens if they don’t have enough of it?

New research from Carnegie, Michigan State University, and France’s National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food, and Environment reveals the complex, interdependent nutrient responses underlying chlorosis, a potentially fatal low-chlorophyll state characterized by an anemic, yellow appearance. Their findings, published in Nature Communications, could pave the way for more environmentally friendly agricultural practices that use less fertilizer and less water.

Nutrients accumulate in chloroplasts and are required for their proper function. For a long time, experts believed that a lack of iron was the sole cause of chlorosis, and farmers frequently used iron to combat leaf yellowing. However, recent research has shown that other nutrients play a role in causing this anemic reaction.

Sue Rhee

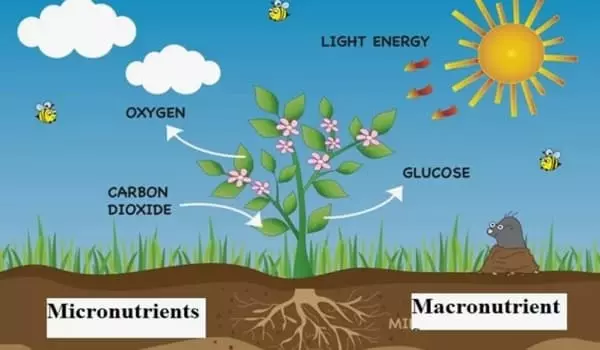

Photosynthesis is a complex biochemical process in which plant cells convert the energy of the Sun into chemical energy, which is then used to fix carbon dioxide from the atmosphere into sugar molecules. It occurs within chloroplasts, which are highly specialized plant cell organelles.

Nutrients accumulate in chloroplasts and are required for their proper function. The research team, led by MSU’s Hatem Rouached and comprised of Carnegie’s Sue Rhee, Hye-In Nam, Yanniv Dorone, Sophie Clowez, and Kangmei Zhao, discovered that a balance of iron and phosphorus is required to prevent chlorosis. The project was started while Rouached was a visiting scholar from France at Carnegie, and it was made possible in part by Brigitte Berthelemot’s generous support to promote Franco-American research collaboration.

“For a long time, experts believed that a lack of iron was the sole cause of chlorosis, and farmers frequently used iron to combat leaf yellowing,” Rhee explained. “However, recent research has shown that other nutrients play a role in causing this anemic reaction.”

To better understand what causes chlorotic leaves, the researchers decided to examine the response to multiple nutrients concurrently rather than one at a time. Plants with chlorosis caused by iron deficiency turned yellow, and photosynthetic activity was reduced, as expected. When the nutrient phosphorus was removed as well, the plant’s leaves began to accumulate chlorophyll and turned green again.

The signaling between the chloroplast, where photosynthesis occurs, and the nucleus, where the cell’s genetic code is stored, explains this unexpected response. Interdisciplinary studies revealed that the ability of the nucleus to regulate gene expression in response to low iron is dependent on the availability of phosphorus. This type of complex layering of nutrient responses indicates that there is still a lot to learn about these communication channels between these two important plant organelles.

The findings of the team could have implications for food crop resilience, which is especially important in a changing climate.

“For example, we need to reconsider fertilizer management,” Rouached concluded. “If we take actions that do not take into account how nutrients interact with one another, we may create conditions that cause plants to fail. Moving forward, it is critical that we correct this thinking for the benefit of global food production.”

A growing global population, as well as the urgency of eradicating hunger and malnutrition, necessitate determined policies and effective actions to ensure long-term growth in agricultural productivity and production. Access to nutritionally adequate and safe food is critical for individual well-being as well as national, social, and economic development. Unless extraordinary efforts are made, an unacceptable proportion of the world’s population, particularly in developing countries, may continue to be chronically malnourished in the coming years, with additional suffering caused by acute periodic food shortages.