Yersinia microorganisms cause various human and animal infections, the most famous of which is the plague, brought about by Yersinia pestis. A family member, Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, causes gastrointestinal sickness and is less dangerous; it normally contaminates the two mice and people, making it a helpful model for concentrating on its connections with the invulnerable framework.

These two microbes, as well as a third close cousin, Y. enterocolitica, which influences pigs and can cause food-borne sickness on the off chance that individuals devour tainted meat, share numerous qualities for all intents and purposes, especially their talent for obstructing the safe framework’s capacity to respond to disease.

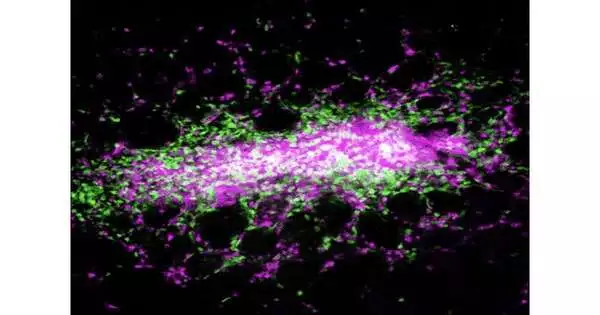

The plague microorganism is blood-borne and transmitted by contaminated insects. Disease in the other two relies upon ingestion. However, the focal point of a significant part of the work in the field had been on collaborations of Yersinia with lymphoid tissues, as opposed to the digestive system. Another investigation of Y. pseudotuberculosis, conducted by a group from Penn’s School of Veterinary Medication and distributed in Nature Microbial Science, exhibits that because of disease, the host-resistant framework shapes little, walled-off sores in the digestion tracts called granulomas. It’s the first time these coordinated assortments of safe cells have been tracked down in the digestive organs because of Yersinia contaminations.

“Our findings point to a previously unknown place where Yersinia can invade and the immune system is activated. These granulomas form in the intestines to regulate the bacterial infection. And we show that if they do not form or are not maintained, the bacteria are able to circumvent immune system control and produce increased systemic infection.”

Igor Brodsky, senior author on the work and a professor and chair of pathobiology at Penn Vet.

The group proceeded to show that monocytes, a sort of resistant cell, support these granulomas. Without them, the granulomas decayed, permitting the mice to be surpassed by Yersinia.

“Our information uncovers a formerly undervalued site where Yersinia can colonize and the invulnerable framework is locked in,” says Igor Brodsky, senior creator of the work and a teacher and chair of pathobiology at Penn Vet. “These granulomas have the structure to control the bacterial contamination in the digestive organs. What’s more, that’s what we show: on the off chance that they don’t shape or neglect to be kept up with, the microbes can defeat the control of the resistant framework and cause more noteworthy foundational disease.”

The discoveries have suggestions for growing new treatments that influence the host’s resistant framework, Brodsky says. A medication that tackled the force of resistant cells to hold Yersinia in line as well as to conquer its guards, the scientists say, might actually dispense with the microorganism through and through.

An original combat zone

Y. pestis, Y. pseudotuberculosis, and Y. enterocolitica share a sharp capacity to dodge invulnerable discovery.

“In each of the three Yersinia contaminations, a trademark is that they colonize lymphoid tissues and can get away from safe control and recreate, cause sickness, and spread,” Brodsky says.

Prior examinations had shown that Yersinia provoked the development of granulomas in the lymph hubs and spleen, but no one had noticed them in the digestive organs until Daniel Sorobetea, an exploration individual in Brodsky’s gathering, investigated the digestive organs of mice contaminated with Y. pseudotuberculosis.

“Since it’s an orally obtained microbe, we were keen on how the microscopic organisms acted in the digestion tracts,” Brodsky says. “Daniel mentioned this underlying objective fact that following Yersinia pseudotuberculosis contamination, there were perceptibly apparent injuries up and down the length of the stomach that had never been portrayed.”

The examination group, including Sorobetea and later Rina Matsuda, a doctoral understudy in the lab, saw that these equivalent injuries were available when mice were tainted with Y. enterocolitica, occurring somewhere around five days after the disease.

A biopsy of the digestive tissues affirmed that the sores were a sort of granuloma, known as a pyogranuloma, made out of different safe cells, including monocytes and neutrophils, one more kind of white platelet that is essential for the body’s bleeding edge in battling microbes and infections.

Granulomas are structures in different illnesses that include constant disease, including tuberculosis, for which Y. pseudotuberculosis is named. Strangely enough, these granulomas — while key in controlling contamination by walling off the irresistible specialist — likewise support a population of the microbes inside those walls.

The group needed to comprehend how these granulomas were both shaped and kept up with, working with mice lacking monocytes as well as creatures treated with an immune response that drains monocytes. In the creatures lacking monocytes, “these granulomas, with their particular design, wouldn’t frame,” Brodsky says.

All things considered, a more muddled and necrotic canker was created, neutrophils were neglected, and the mice were less ready to control the attacking microbes. These creatures experienced elevated levels of microorganisms in their digestive organs and succumbed to their contamination.

Preparation for what’s in store

The scientists accept the monocytes are responsible for enlisting neutrophils to the site of contamination and accordingly sending off the arrangement of the granuloma, assisting with controlling the microscopic organisms. This driving job for monocytes might exist past the digestive organs, the specialists accept.

“We estimate that it’s an overall job for the monocytes in different tissues too,” Brodsky says.

However, the revelations likewise highlight the digestive organs as a vital site of commitment between the insusceptible framework and Yersinia.

“Past to this review, we were aware of Peyer’s patches as being the essential site where the body associates with the external climate through the mucosal tissue of the digestion tracts,” says Brodsky. Peyer’s patches are little areas of lymphoid tissue present in the digestive organs that effectively manage the microbiome and fight off contamination.

In future work, Brodsky and partners desire to keep on sorting out the component by which monocytes and neutrophils contain the microscopic organisms, a work they’re tightening in a joint effort with Bright Shin’s lab in the Perelman Institute of Medical Research’s microbial science division.

A more profound understanding of the sub-atomic pathways that control this resistant reaction might one day at some point offer advances into having coordinated safe treatments, by which a medication could steer the results for the host’s invulnerable framework, releasing its strength to completely kill the microbes as opposed to just corralling them in granulomas.

“These treatments have caused a blast of fervor in the disease field,” Brodsky says, “reviving the resistant framework. Reasonably, we can likewise contemplate how to persuade the safe framework to be revitalized to go after microbes in these settings of ongoing contamination as well.”

More information: Daniel Sorobetea et al, Inflammatory monocytes promote granuloma control of Yersinia infection, Nature Microbiology (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41564-023-01338-6

Journal information: Nature Microbiology