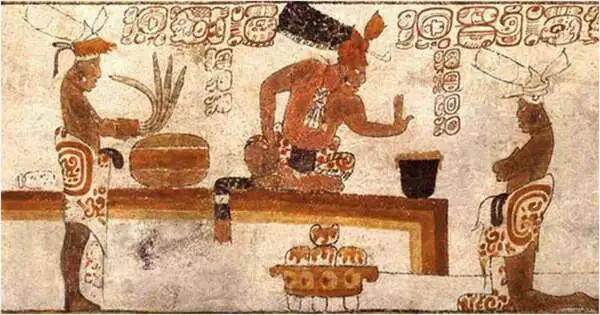

Cacao was considered holy by the ancient Maya and was used as currency, but only for specific services and strict customs. It’s the begetter plant of chocolate, and ideas of extravagance are implanted in its legend.

The common conviction: cacao was more accessible to, even constrained by, the general public’s higher classes of eminence. Past endeavors to recognize cacao in pottery zeroed in on profoundly improving vessels related to tip-top formal settings—think fancy drinking jars—prompting suspicions about how cacao was conveyed and who could get to it.

What might be said about the ranchers who developed cacao and the networks of individuals who lived among these plantations? What of the overall population?

Another concentrate by UC St. Nick Barbara analysts Anabel Portage and Mattanjah de Vries poses these questions—and addresses them—by analyzing cacao buildups from old pottery. Their outcomes, distributed in the Procedures of the Public Foundation of Sciences, show that cacao was, as a matter of fact, open to the general population and was utilized in festivals at all levels of society.

“The finding of cacao chemical signatures enabled the investigation, but it turns out that the major active element, theobromine, is not sufficiently discrete to be certain of the cacao attribution,”

Researchers Anabel Ford

For some time, it had been accepted that cacao for the Maya was a tip-top select, said Passage, an anthropologist and head of the MesoAmerican Exploration Place at UC St. Nick’s Barbara, who for a long time has been leading examinations in the old Maya city of El Pilar. “We presently realize this isn’t true. The guzzling of cacao was an extravagance open to all. The significance is that it was a necessity of the customs related to it. “

To test the eliteness of cacao use, the work analyzes 54 archeological clay sherds. Beginning at El Pilar, which is located between Belize and Guatemala, the sherds can be traced to Late Exemplary period cities and private settings, addressing a diverse range of old Maya occupants.The review incorporates a compound examination of these sherds—explicitly of the biomarkers for cacao: caffeine, theobromine, and theophylline.

Mesoamerica and the Maya Swamps, with El Pilar at the ecotone between the inside and the Belize Stream, with other major city places shown. MesoAmerican Exploration Place is credited.

“The revelation of compound marks of cacao made the examination conceivable, yet the super dynamic fixing, theobromine, it turns out, isn’t adequately discrete to be sure of the cacao attribution,” said Portage. “Mattanjah (de Vries) and his understudies, in their compound examination, experienced the chance of recognizing theophylline, a particular part of cacao that couldn’t be mistaken for anything more. His work was not archeological, yet he saw the potential for an interdisciplinary task. “

A recognized teacher and division chair of science and organic chemistry at UC St. Nick’s, de Vries has for some time been concentrating on how DNA bases—the building blocks of life—and comparable particles respond to UV light and, he said, whether UV light “might have had an impact on an early Earth, in the manner in which nature chose those building blocks from an early stage soup of many such mixtures.”

Eventually, I understood that a portion of the mixtures we had been concentrating on in this beginning of life science project happen in cacao, and hence can act as biomarkers for cacao,” de Vries said. “Since we had previously explored the spectroscopy of these mixtures exhaustively, this introduced a chance to apply that skill to the location of these biomarkers for paleohistory.”

“We can find a hard to find little item if we understand what the needle resembles; for this situation, the objective particle was a sure biomarker for cacao,” he added. “That capacity made this examination conceivable.”

In their choice of pottery to test, Passage and de Vries focused on the jars from which cacao was logically alcoholic. They likewise tried bowls, containers, and plates. All vessel types had proof of cacao.

“This was a shock from the start,” Portage said, “yet giving idea to the presence and comprehension of their purposes, bowls would be great for blending, containers would be ideal for warming the beverage (a customary cacao planning), and plates would be proper for serving food with sauces that can contain cacao, (for example, mole poblano).

“Since it is now so obvious that the presence of cacao is in all vessel types, we want to comprehend the more prominent dispersion and utilization of these significant family structures,” Portage added. “What is basic in our work is that the information I gathered in the El Pilar—Belize Stream region stresses the normal families and, in addition to the tip-top focus, Our examination hence kicks things off on the ID and the conveyance. “

More information: Anabel Ford et al, New light on the use of Theobroma cacao by Late Classic Maya, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2121821119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences