When we see metals in our daily lives, we see them as shiny.That is on the grounds that normal metallic materials are intelligent at apparent light frequencies and will return any light that strikes them. While metals are appropriate for leading power and intensity, they aren’t normally considered a way to direct light.

Yet, in the thriving field of quantum materials, analysts are progressively tracking down models that challenge assumptions regarding how things ought to act. In a new examination distributed in Science Advances, a group led by Dmitri Basov, Higgins Teacher of Physical Science at Columbia College, depicts a metal fit for leading light. “These outcomes oppose our everyday encounters and normal origins,” said Basov.

The work was driven by Yinming Shao, presently a postdoc at Columbia who moved as a Ph.D. understudy when Basov moved his lab from the College of California San Diego to New York in 2016. While working with the Basov bunch, Shao has been investigating the optical properties of a semimetal material known as ZrSiSe. In 2020, in Nature Physical Science, Shao and his partners showed that ZrSiSe imparts electronic likenesses to graphene, the first alleged Dirac material found in 2004. ZrSiSe, in any case, has upgraded electronic connections that are uncommon for Dirac semimetals.

“It’s similar to a sandwich: one layer acts as a metal, while the next acts as an insulator. When this happens, light begins to interact with the metal in an odd way at specific frequencies. Instead of just bouncing off, it might travel into the material in a zigzag pattern, a process known as hyperbolic propagation.”

Yinming Shao, now a postdoc at Columbia who transferred as a Ph.D.

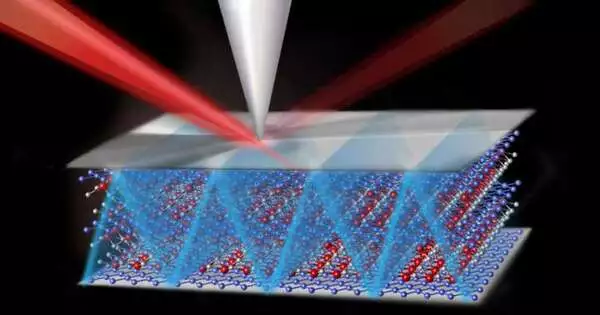

While graphene is a solitary, iota-thin layer of carbon, ZrSiSe is a three-layered metallic gem comprised of layers that act diversely in the in-plane and out-of-plane headings, a property known as anisotropy. “It’s similar to a sandwich: one layer behaves like a metal while the following layer behaves like a cover,” made sense of Shao. “At the point when that occurs, light begins to connect curiously with the metal at specific frequencies. Rather than simply bobbing off, it can go inside the material in a crisscross pattern, which we call “exaggerated spread.”

In their ongoing work, Shao and his partners at Columbia and the College of California, San Diego, noticed such a crisscross development of light, alleged exaggerated waveguide modes, through ZrSiSe tests of changing thicknesses. Such waveguides can direct light through a material and, here, result from photons of light blending in with electron motions to make mixture quasiparticles called plasmons.

Although the circumstances for creating plasmons that can spread exaggeratedly are met in many layered metals, it is the novel scope of electron energy levels, called the electronic band structure, of ZrSiSe that permitted the group to notice them in this material. Hypothetical help to assist with making sense of these trial results came from Andrey Rikhter in Michael Fogler’s gathering at UC San Diego; Umberto De Giovannini and Holy Messenger Rubio at the Maximum Planck Foundation for the Construction and Elements of Issue; and Raquel Queiroz and Andrew Millis at Columbia. (Rubio and Millis are likewise partnered with the Simons Establishment’s Flatiron Foundation).

Plasmons can “amplify” highlights in an example, allowing scientists to see beyond the diffraction limits of an optical magnifying lens, which can’t determine subtleties lower than the frequency of light they use in any case.”Utilizing exaggerated plasmons, we could determine that includes under 100 nanometers utilizing infrared light that is many times longer,” said Shao.

ZrSiSe can be stripped to various thicknesses, making it an intriguing choice for nano-optics research that favors super thin materials, said Shao. Yet, it’s logical that it’s not, by any means, the only material to be important — from here, the gathering needs to investigate others that share likenesses with ZrSiSe yet could have much better waveguiding properties. That could be useful to analysts in fostering more effective optical chips and better nano-optics ways to deal with investigating key inquiries regarding quantum materials.

“We need to utilize optical waveguide modes, similar to what we’ve tracked down in this material and desire to track down in others, as columnists of fascinating new physical science,” said Basov.

More information: Yinming Shao et al. Infrared plasmons propagate through a hyperbolic nodal metal. Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.add6169

Journal information: Nature Physics , Science Advances