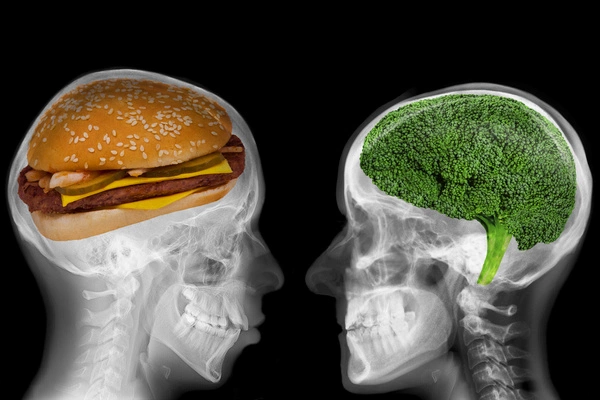

Excess fat in your diet, particularly saturated fats, can raise your cholesterol, increasing your risk of heart disease. According to new research, fatty foods may not only increase your waistline but also mess with your brain.

An international study led by University of South Australia neuroscientists Professor Xin-Fu Zhou and Associate Professor Larisa Bobrovskaya found a clear link between mice fed a high-fat diet for 30 weeks, resulting in diabetes, and a subsequent deterioration in cognitive abilities, including anxiety, depression, and worsening Alzheimer’s disease.

A small amount of fat is required for a healthy, balanced diet. Fat contains essential fatty acids, which the body cannot produce on its own. Fat aids in the absorption of vitamins A, D, and E. Because these vitamins are fat-soluble, they can only be absorbed with the help of fats. Any fat that is not used by your cells or converted into energy is stored as body fat. Similarly, unutilized carbohydrates and proteins are converted into body fat.

Our findings underline the importance of addressing the global obesity epidemic. A combination of obesity, age, and diabetes is very likely to lead to a decline in cognitive abilities, Alzheimer’s disease, and other mental health disorders.

Assoc Prof Bobrovskaya

Mice with impaired cognitive function were also more likely to gain excessive weight due to poor metabolism caused by brain changes. Researchers from Australia and China have published their findings in Metabolic Brain Disease.

UniSA neuroscientist and biochemist Associate Professor Larisa Bobrovskaya says the research adds to the growing body of evidence linking chronic obesity and diabetes with Alzheimer’s disease, predicted to reach 100 million cases by 2050.

“Obesity and diabetes impair the central nervous system, exacerbating psychiatric disorders and cognitive decline. We demonstrated this in our study with mice,” Assoc Prof Bobrovskaya says.

In the study, mice were randomly allocated to a standard diet or a high-fat diet for 30 weeks, starting at eight weeks of age. Food intake, body weight, and glucose levels were monitored at different intervals, along with glucose and insulin tolerance tests and cognitive dysfunction.

Although the researchers admit that finding participants willing to follow restrictive diets for the three-month study – or partners willing to help them stick to those diets – was difficult, those who followed a modified Atkins diet (very low carbohydrates and extra fat) had small but measurable improvements on standardized memory tests compared to those who followed a low-fat diet.

When compared to mice fed a standard diet, those on the high-fat diet gained a lot of weight, developed insulin resistance, and began behaving abnormally. While fed a high fat diet, genetically modified Alzheimer’s disease mice showed significant deterioration in cognition and pathological changes in the brain.

“Obese people have a 55% increased risk of developing depression, and diabetes doubles that risk,” says Assoc Prof Bobrovskaya. “Our findings highlight the critical importance of combating the global obesity epidemic. Obesity, age, and diabetes are all known risk factors for cognitive decline, Alzheimer’s disease, and other mental health disorders.”

When comparing the results of delayed recall tests (the ability to recall something told or shown to them a few minutes earlier), those who adhered to the modified Atkins diet improved by a couple of points on average (about 15% of the total score), while those who did not adhere to the diet dropped a couple of points.

The researchers say the biggest hurdle for researchers was finding people willing to make drastic changes to their eating habits and partners willing to enforce the diets. The increase in carbohydrate intake later in the study period, they said, suggests that the diet becomes unpalatable over long periods.