A group of specialists from the Instituto Gulbenkian de Ciência (IGC) uncovered that cells of the cerebrum can recognize the presence of jungle fever parasites in the blood, setting off the basic irritation of cerebral jungle fever. This discovery revealed new targets for adjuvant treatments that could limit brain damage in the early stages of the disease and avoid neurological sequelae.

Cerebral jungle fever is an extremely complex disease with Plasmodium falciparum, the most deadly of the parasites causing intestinal sickness. This type of illness appears through hindered awareness and trance-like states and influences predominantly kids under 5, being one of the primary drivers of death in this age group in nations of Sub-Saharan Africa. The people who endure are often impacted by weakening neurological sequelae like engine deficiencies, loss of motion and discourse, hearing, and visual debilitation.

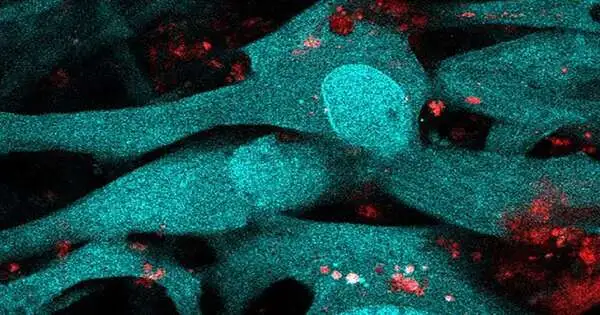

To keep specific particles and cells from arriving at the mind, which would upset its normal working, particular cells from the internal coating of veins, the endothelial cells, are firmly held together, framing a hindrance between the blood and this organ. Cerebral jungle fever results from an excessive fiery reaction to contamination, which prompts huge changes in this hindrance and, therefore, neurological difficulties.

Throughout the past years, experts in this field have stood out for a particle called interferon-, which is by all accounts related to this neurotic cycle. Purportedly for disrupting viral replication, this profoundly incendiary particle has different sides: it can either be safeguarding or cause tissue annihilation. For instance, it is known, for instance, that in spite of its antiviral job in COVID-19, at a given focus and period of contamination, it can cause lung harm. A comparable dynamic is remembered to happen in cerebral jungle fever. Nonetheless, we actually don’t have the foggiest idea what prompts the discharge of interferon-, nor the fundamental cells included.

“We assumed brain endothelial cells operated later in the process, but we discovered that they are involved from the start. Normally, we link the first stage of an infection’s reaction with immune system cells. These are already known to respond, but cells in the brain and possibly other organs have the potential to detect infection since they share the same sensors.”

Teresa Pais, a post-doctoral researcher at the IGC

A new study led by the IGC and published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences discovered that endothelial cells in the brain play an important role in detecting jungle fever parasite contamination early on.These recognize the disease through an inside sensor, which sets off an outpouring of events, beginning with the creation of interferon-. Then, they discharge a flagging particle that draws in cells of the safe framework to the cerebrum, starting the fiery cycle.

To arrive at these resolutions, specialists utilized mice that imitate a few side effects depicted in human jungle fever and a hereditary control framework that permitted them to erase this sensor in a few sorts of cells. When they erased this sensor in cerebrum endothelial cells, they reasoned that the creature’s side effects were not as serious and that they kicked the bucket less from the contamination. That was the point at which they understood these synapses contributed significantly to the pathology of cerebral intestinal sickness.

“We thought mind endothelial cells acted at a later stage, yet we wound up understanding that they were members all along,” makes sense of Teresa Pais, a post-doctoral scientist at the IGC and the first creator of the review. “Regularly we partner this underlying period of the reaction to contamination with cells of the safe framework. “These are now known to be answered, yet cells of the cerebrum, and perhaps different organs, additionally have this capacity to detect the disease since they have similar sensors,” she adds.

Be that as it may, what truly shocked the specialists was the element actuating the sensor and setting off this cell reaction. This component isn’t anything more than a result of the movement of the parasite. Once in the blood, the parasite attacks the host’s red platelets, where it duplicates. Here, it digests hemoglobin, a protein that transports oxygen, to get supplements.

During this cycle, a particle named heme is shaped, and it very well may be shipped in minuscule particles in the blood that are incorporated by endothelial cells. At the point when this occurs, heme goes about as an alert for the invulnerable framework. “We weren’t expecting that heme could enter cells along these lines and enact this reaction, including interferon-in endothelial cells,” the scientist admits.

The scientists were able to identify a subatomic component that is fundamental to the obliteration of mind tissue during disease with the intestinal sickness parasite and, as a result, new therapeutic targets.The following stage will be to attempt to restrain the movement of this sensor inside the endothelial cells and comprehend in the event that we can follow up on the host’s reaction and stop cerebrum pathology in an underlying stage,” makes sense of Carlos Penha Gonçalves, head examiner of the group who drove the review.

“In the event that we could involve inhibitors of the sensor in lining up with antiparasitic medicates, perhaps we could stop the deficiency of neuronal capability and keep away from sequelae, which are a significant issue for youngsters enduring cerebral jungle fever,” he finishes up.

More information: Teresa F. Pais et al, Brain endothelial STING1 activation by Plasmodium -sequestered heme promotes cerebral malaria via type I IFN response, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2206327119

Journal information: Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences