Urban communities are liable for just about one-fifth of the worldwide methane outflows brought about by human activity. Yet, most urban areas don’t catch data about the full scope of the wellsprings of this strong ozone-harming substance. In 2020, a group led by McGill College estimated methane outflows from different sources across the city of Montreal.

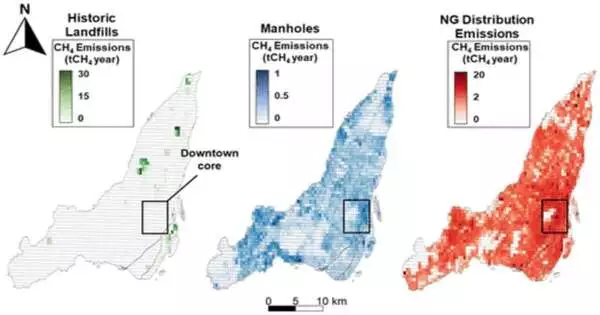

The analysts tracked down that two of the four most significant wellsprings of methane outflows in the city (memorable landfills and sewer vents) are excluded from the city’s civil ozone-harming substance inventories, making it hard to handle the issue completely or arrive at the city’s objective of being carbon-unbiased by 2050.

The review gives the main arrangement of direct estimations of methane outflows in Montreal and in the area of Quebec.

The review gives definite and explicit estimations of methane outflows by source, like the kind of sewer vent or the sort of petroleum gas framework. The outcomes, which feature the significance of gathering data about the particular wellsprings of methane outflows to set up relief systems that are adjusted to every particular circumstance, ought to be of interest not exclusively to analysts across Canada and all over the planet, but also to strategy creators.

“Cities are particularly positioned to reduce methane emissions because they face less political challenges than larger bodies like provinces, states, territories, or countries,”

Mary Kang, an assistant professor in McGill’s Department of Civil Engineering

“Urban communities are remarkably situated to relieve methane outflows as they face less political difficulties than bigger bodies like regions, states, domains, or nations,” says Mary Kang, an associate teacher in McGill’s Branch of Structural Designing and the senior creator on the paper distributed as of late in Natural Science and Innovation.

“Nevertheless, city ozone-harming substance inventories frequently misjudge outflows and will generally be founded on a couple of estimations made somewhere else, making it hard to foster noteworthy relief systems.”

Vital insights regarding wellsprings of outflows clear the way for informed choices.

To furnish the city with noteworthy relief systems, the group estimated methane outflows from nearly 600 unique sources across the city, covering memorable landfills and sewer vents (the second and third biggest wellsprings of methane discharges, separately), as well as holes from flammable gas dispersion.

“Pursuing decisions about how to lessen methane outflows in a productive and savvy way will include adjusting different contemplations, contingent upon the wellspring of the emanations,” makes sense to James Williams, the Ph.D. understudy who is the main creator on the paper.

“For example, notable landfills have the potential for the best decrease in the volume of methane outflows, yet they will include the most elevated relief costs except if the decision is made to zero in on just the most elevated landfills.” Extending the fixed rates of high-emanating modern meters for outflows from petroleum gas releases could significantly reduce relief expenses and discharges.Yet, doing likewise with regards to private meters would prompt more modest decreases at a much greater expense.

To get the full picture of how methane outflows can be decreased, the analysts intend to take extra estimations from all methane sources around the city to guarantee that they aren’t feeling the loss of the greatest producers. They likewise plan to check out methane emissions from sources like metropolitan streams and channels.

More information: James P. Williams et al, Differentiating and Mitigating Methane Emissions from Fugitive Leaks from Natural Gas Distribution, Historic Landfills, and Manholes in Montréal, Canada, Environmental Science & Technology (2022). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.2c06254

Journal information: Environmental Science and Technology