Over a hundred years of protected fish examples offer an uncommon look into long-haul patterns in parasite populations. New exploration from the College of Washington shows that fish parasites dove from 1880 to 2019, a 140-year stretch when Puget Sound — their territory and the second biggest estuary in the central U.S. — warmed fundamentally.

The review, distributed over a seven-day stretch beginning Jan. 9 in the Procedures of the Public Foundation of Sciences, is the world’s biggest and longest dataset of natural life parasite overflow. It suggests that parasites might be particularly defenseless against an evolving environment.

“Individuals by and large think that environmental change will make parasites flourish and that we will see an expansion in parasite episodes as the world warms,” said lead creator Chelsea Wood, a UW academic partner in oceanic and fishery sciences. “For some parasite species, that might be valid; however, parasites rely upon hosts, and that makes them especially weak in an impactful world where the destiny of hosts is being reshuffled.”

While certain parasites have solitary host animal varieties, numerous parasites travel between different species. Eggs are conveyed in one host animal type, the hatchlings arise and contaminate another host, and the adults may arrive at development in a third host prior to laying eggs.

For parasites that depend on at least three host species during their lifecycle, including the greater part of the parasite species recognized in the review’s Puget Sound fish, examination of memorable fish examples showed a 11% typical decay each 10 years in overflow. Of the 10 parasite species that had vanished totally by 1980, nine depended on at least three hosts.

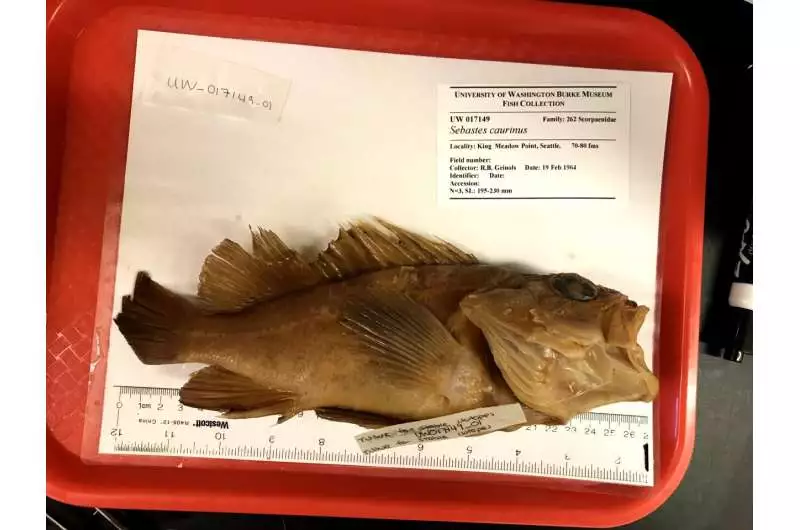

This copper rockfish (Sebastes caurinus) was gathered in 1964 in Puget Sound. The study included eight fish species and observed a dramatic decrease in parasite abundance over time.

“Our outcomes show that parasites with a couple of host animal groups remained pretty predictable, however, parasites with at least three hosts crashed,” Wood said. “The level of decline was extreme. It would spark preservation efforts if it occurred in species that people care about, such as well-evolved creatures or birds.

And keeping in mind that parasites motivate dread or disdain—pparticularly for individuals who partner them with sickness in themselves, their children, or their pets—tthe outcome is stressful news for environments, Wood said.

“Parasite biology is truly in its early stages, however, what we can be sure of is that these complex-lifecycle parasites most likely assume a significant role in pushing energy through food networks and in supporting top dominant hunters,” Wood said. She is one of the creators of a 2020 report outlining a preservation plan for parasites.

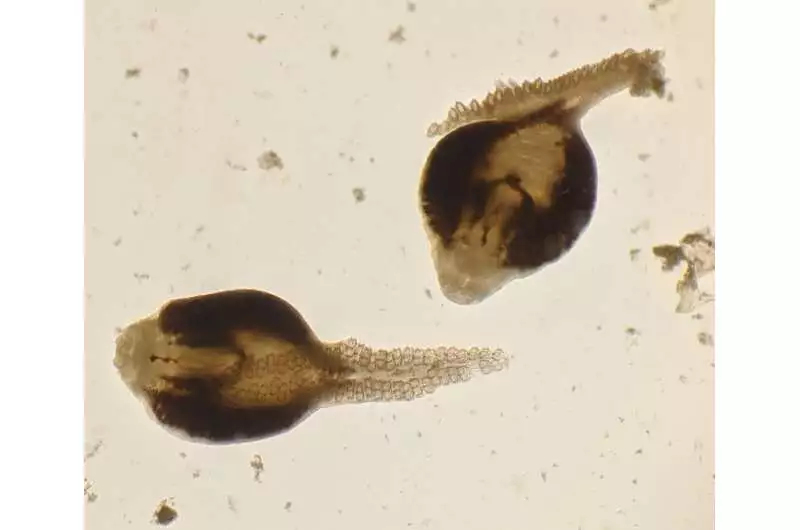

These monogenean worms (Microcotyle sebastis) were analyzed from the gills of a safeguarded copper rockfish example from the UW Fish Assortment at the Burke Historical Center.

Wood’s review is among the quick to utilize another technique for restoring data on parasite populations of the past. Well-evolved creatures and birds are safeguarded with taxidermy, which holds parasites just on skin, quills, or fur. Be that as it may, fish, reptiles, and land- and water-proficient examples are safeguarded in liquid, which likewise protects any parasites living inside the creature at the hour of its demise.

The review zeroed in on eight types of fish that are normal in the background assortments of regular history galleries. Most came from the UW Fish Assortment at the Burke Historical Center of Normal History and Culture. The creators painstakingly cut into the protected fish examples and afterward recognized and counted the parasites they found inside prior to returning the examples to the historical centers.

“It required a long investment.” “It’s absolutely not for the weak-willed,” Wood said. “I’d very much want to put these fish in a blender and utilize a genomic strategy to distinguish their parasites’ DNA; however, the fish were first saved with a liquid that shreds DNA. So what we did was simply ordinary shoe-calfskin parasitology.

Examples of Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii) on a rack in the Burke Exhibition Hall’s UW Fish Assortment. This background assortment provided a large portion of the examples utilized in the 140-year investigation of parasite overflow.

Among the multi-celled parasites they found were arthropods, or creatures with an exoskeleton, including scavengers, as well as what Wood depicts as “incredibly dazzling tapeworms,” the Trypanorhyncha, whose heads are equipped with snare-covered arms. Altogether, the group counted 17,259 parasites of 85 kinds in 699 fish.

To make sense of the parasite declines, the creators thought about three potential causes: how bountiful the host species was in Puget Sound; contamination levels; and temperature at the sea’s surface. The variable that best explained the decrease in parasites was ocean surface temperature, which climbed by 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit) in Puget Sound from 1950 to 2019.

A parasite that requires various hosts resembles a fragile Rube Goldberg machine, Wood said. The intricate series of steps they must complete to complete their lifecycle renders them defenseless against interruption at any point along the way.

A container of liquid-safeguarded fish examples from the UW Fish Assortment is at the Burke Historical Center. These fish were gathered in the Hood Waterway in 1991.

“This study shows that significant parasite declines have occurred in Puget Sound. “In the event that this can happen inconspicuously in a biological system as concentrated as this one, what other place could it work out?” Wood said. “I trust our work moves different scientists to contemplate their own central environments, distinguish the right historical center examples, and see whether these patterns are exceptional to Puget Sound or something that is happening in other spots also.

“Our outcome causes us to notice the way that parasitic species may be in genuine peril,” Wood added. “That could mean awful stuff for us—less worms, however, and less of the parasite-driven biological system benefits that we’ve come to rely upon.”

The UW Fish Assortment is a state-upheld office that houses in excess of 300,000 adult fish specimens. The container on the left contains herring (Clupea pallasii) gathered in 1952.

Co-creators are Rachel Welicky at Pennsylvania’s Neumann College, who accomplished this work as a UW postdoctoral specialist; Whitney Preisser at Georgia’s Kennesaw State College, who accomplished this work as a UW postdoctoral scientist; Katie Leslie, a UW exploration technician; Natalie Mastick, a UW doctoral understudy; Katherine Maslenikov, director of the UW Fish Assortment at the Burke Gallery of Normal History and Culture; Luke Tornabene and Timothy Essington, employees in seagoing and fisheries sciences at the UW; Correigh Greene at NOAA’s Northwest Fisheries Science Center; and John M. Kinsella at HelmWest Research facility in Missoula, Montana;

More information: Wood, Chelsea L., A reconstruction of parasite burden reveals one century of climate-associated parasite decline, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2211903120. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2211903120