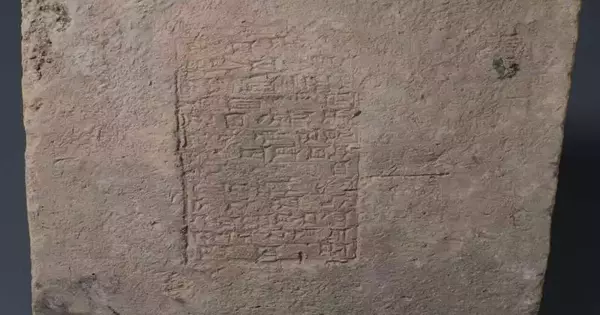

A new study by researchers from the University of London reveals that ancient bricks engraved with the names of Mesopotamian kings shed light on a mysterious anomaly in the Earth’s magnetic field that occurred 3,000 years ago.

The exploration, distributed in the Procedures of the Public Foundation of Sciences, portrays how changes in the world’s attractive field were engraved on iron oxide grains inside old earth blocks and how researchers had the option to reproduce these progressions from the names of the lords recorded on the blocks.

The team hopes that by utilizing this “archaeomagnetism,” which looks for signs of the Earth’s magnetic field in archaeological objects, they will be able to better date artifacts and improve the history of the Earth’s magnetic field.

“We frequently rely on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates to get a sense of the chronology in ancient Mesopotamia,” stated co-author Professor Mark Altaweel of the UCL Institute of Archaeology. Nonetheless, probably the most well-known social remaining parts, like blocks and earthenware production, can’t regularly be effortlessly dated in light of the fact that they don’t contain natural material. Using archaeomagnetism, this work now contributes to the creation of a crucial dating baseline that enables others to profit from absolute dating.”

“To get a sense of chronology in ancient Mesopotamia, we frequently rely on dating methods such as radiocarbon dates. However, some of the most prevalent cultural remnants, like as bricks and ceramics, are difficult to date because they lack organic content. This work now contributes to the establishment of an essential dating baseline, allowing others to profit from absolute dating using archaeomagnetism.”

Co-author Professor Mark Altaweel (UCL Institute of Archaeology).

The world’s attractive field debilitates and reinforces, after some time, changes that engrave a particular mark on hot minerals that are delicate to the attractive field.

The group examined the attractive mark in grains of iron oxide minerals implanted in 32 dirt blocks, beginning in archeological locales all through Mesopotamia, which presently covers current Iraq. The strength of the planet’s attractive field was engraved upon the minerals when they were first terminated by the brickmakers millennia prior.

Each brick had the name of the king on it when it was made, which archaeologists have dated to a variety of likely times. Together, the engraved name and the deliberate attractive strength of the iron oxide grains offered a verifiable guide to the progressions to the strength of the world’s attractive field.

The specialists had the option to affirm the presence of the “Levantine Iron Age geomagnetic peculiarity,” a period when Earth’s attractive field was areas of strength for surprisingly present-day Iraq between around 1050 and 550 BCE for indistinct reasons. Although data from the southern Middle East itself was sparse, the anomaly has been observed as far away as China, Bulgaria, and the Azores.

Lead creator Teacher Matthew Howland of Wichita State College said, “By contrasting old antiques with what we are familiar with, old states of the attractive field, we can appraise the dates of any relics that were warmed up in antiquated times.”

The team used a magnetometer to precisely measure tiny fragments taken from the bricks’ broken faces in order to measure the iron oxide grains.

This data also gives archaeologists a new way to help date some ancient artifacts by mapping the changes in Earth’s magnetic field over time. The attractive strength of iron oxide grains implanted inside terminated things can be estimated and then paired up with the known qualities of Earth’s noteworthy attractive field. Unlike radiocarbon dating, which can only pinpoint an artifact’s date to within a few hundred years, kings ruled for years to decades, providing a higher level of certainty.

An extra advantage of the archaeomagnetic dating of the relics is it can help students of history all the more unequivocally pinpoint the rules of a portion of the old lords that have been fairly equivocal. However, the length and request of their rules are notable. There has been conflict inside the archeological local area about the exact years they took the lofty position, which came about because of deficient authentic records. “Low Chronology” is an archaeological understanding of the kings’ reigns that the researchers found to be consistent with their method.

The team also discovered that the Earth’s magnetic field appeared to change dramatically over a relatively short period of time in five of their samples taken between 604 and 562 BCE, supporting the possibility of rapid intensity spikes.

Co-creator Teacher Lisa Tauxe of the Scripps Foundation of Oceanography said, “The geomagnetic field is quite possibly the most cryptic peculiarity in studies of the planet. The very much dated archeological remaining parts of the rich Mesopotamian societies, particularly blocks recorded with names of explicit rulers, give an extraordinary chance to concentrate on changes in the field strength in high time, following changes that happened more than quite a few years or even less.”

More information: Howland, Matthew D. et al. Exploring geomagnetic variations in ancient mesopotamia: Archaeomagnetic study of inscribed bricks from the 3rd–1st millennia BCE, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2023). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2313361120