Each year, approximately 14 million tons of plastic end up in the ocean. In any case, that isn’t the main water source where plastic addresses a huge interruption.

“We found microplastics in each lake we examined,” said Ted Harris, partner research teacher for the Kansas Organic Study and Place for Natural Exploration at the College of Kansas.

“Some of these lakes are clear and beautiful places to go on vacation. In any case, we found such places to be ideal instances of the connection among plastics and people.”

The global Global Lake Ecological Observatory Network (GLEON), which studies processes and phenomena in freshwater environments, includes 79 researchers like Harris. Their most recent paper, “Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs,” shows that freshwater environments actually have higher concentrations of plastic than ocean “garbage patches.” The article is distributed in Nature.

“The simple act of people swimming and wearing clothing with microplastic fibers results in microplastics getting everywhere.”

Harris teamed with Rebecca Kessler, his former student and recent KU graduate,

For his job, Harris collaborated with Rebecca Kessler, his previous understudy and late KU graduate, to test two Kansas lakes (Clinton and Perry) and the Cross Repository at the KU Field Station.

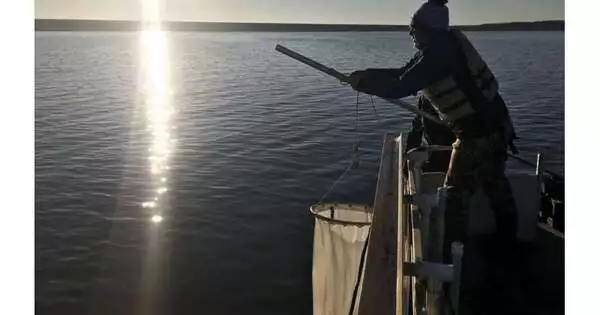

“That involved us going out, ringing a net with minuscule openings in it, hauling it for around two minutes, then gathering those examples of microplastics and sending them off to (the lead specialists),” Kessler said.

The examination project was planned and facilitated by the Inland Water Environment and The Executive Research Gathering of the College of Milano-Bicocca, Italy (headed by Barbara Leoni and Veronica Nava). The group examined the surface waters of 38 lakes and supplies disseminated across slopes of geological position and limnological characteristics. It found plastic debris in every lake and reservoir it examined.

Harris stated, “This paper basically shows that the more people, the more plastic.” Places like Clinton Lake are somewhat low in microplastics on the grounds that, while there are numerous creatures and trees, there aren’t many people, compared with some places like Lake Tahoe, where individuals are residing around it. Despite the fact that the microplastics originate in some of these lakes, which appear to be pristine and beautiful,

Harris said that a large number of the plastics are from something as obviously harmless as Shirts.

“The basic demonstration of individuals getting into swimming and having clothing that has microplastic filaments in it prompts microplastics to get all over,” he said.

The GLEON concentrate on refers to two kinds of water bodies that are especially defenseless against plastic defilement: lakes and supplies in thickly populated and urbanized regions; what’s more, those with raised affidavit regions, long water maintenance times, and elevated degrees of anthropogenic impact.

Harris stated, “I didn’t know a lot about microplastics versus large plastics when we started the study.”

“At the point when this paper expresses ‘focuses so much or more regrettable than the trash fix,’ you generally consider the enormous containers and stuff; however, you’re not thinking about all that more modest stuff. Lake Tahoe is one of the lakes with the greatest impact on microplastics, despite the fact that it does not have a significant trash patch. Those are plastics that are hard to see with the naked eye, but when you look through a telescope at 40,000 times magnification, you can see tiny, jagged pieces and other particles the same size as algae or smaller.”

Harris and Kessler were excited to participate in this project for the purpose of bringing attention to a region of the United States that is frequently overlooked.

“In this review, there’s one speck in the nation, and that is our example,” he said. “In Iowa, Missouri, and Colorado, there’s this colossal area of region that has water bodies, yet we frequently don’t get them into those gigantic worldwide examinations. So it was truly significant for me to make Kansas famous by seeing and contextualizing what these distinctions are in our lakes.”

Harris has worked at KU since around 2013, where his exploration centers around oceanic nature. Kessler earned a degree in ecology, evolutionary biology, and organismal biology from KU in 2022.

“The greatest focus point from our review is that microplastics can be tracked down in all lakes,” Kessler said. “Clearly, there are various fixations. In any case, they are, in a real sense, all over. Also, the greatest contributing component to these microplastics is human connection with the lakes.”

More information: Veronica Nava et al, Plastic debris in lakes and reservoirs, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06168-4