What could be compared to multiple million plastic jugs tumbling from the sky?

The review, published in Natural Science and Innovation, showed that huge quantities of microplastics in Auckland’s air are of tiny sizes, raising worries about the potential for particles to be breathed in and amass in the human body. Analysts all over the planet are probably going to have decisively undercounted airborne microplastics, says lead creator Dr. Joel Rindelaub of the School of Compound Sciences at Waipapa Taumata Rau, College of Auckland.

The levels found in Auckland’s air were commonly higher than those kept in London, Hamburg, and Paris lately, on the grounds that researchers in the new review utilized modern compound techniques to find and examine particles as small as 0.01 of a millimeter.

The mean (normal) number of airborne microplastics identified in a square meter in a day was 4,885. That contrasts with 771 in London (revealed in a review distributed in 2020), 275 in Hamburg (2019), and 110 in Paris (2016). “Future work needs to measure precisely how much plastic we are taking in,” says Dr. Rindelaub. “It’s turning out to be increasingly evident that this is a significant course of openness.”

“The generation of airborne microplastics by breaking waves could play an important role in the global transport of microplastics. It may also help explain how some microplastics enter the atmosphere and travel to faraway locations such as New Zealand.”

Dr. Rindelaub.

The review is quick to compute the total mass of microplastics in a city’s air. Waves breaking in the Hauraki Bay might assume a vital role in Auckland’s concern by sending water-borne microplastics high up.

That impact appeared to be working when Rindelaub and his partners, including Ph.D. understudy Wenxia Fan and teacher Jennifer Salmond, recorded expanded numbers after breezes from the bay got a move on, logically prompting greater waves and more transmission.

“The creation of airborne microplastics from breaking waves could be a vital piece of the worldwide transportation of microplastics,” says Rindelaub. “Also, it could assist with making sense of how some microplastics get into the air and are conveyed to remote spots, similar to here in New Zealand.”

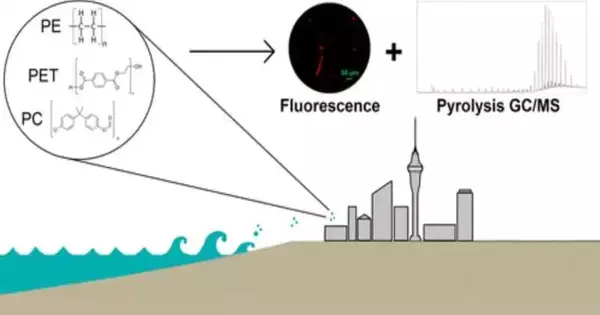

Molecule sizes are altered with the twist course. At the point when winds ignored the Auckland downtown area, the microplastics downwind were bigger, showing the plastics had gone through less natural maturing and came from a nearer source. Polyethylene (PE) was the most significant substance identified, trailed by polycarbonate (PC) and polyethylene terephthalate (PET). Polyethylene and PET are used to bundle materials, while PC is utilized in electrical and electronic applications. Each of the three is also used in the construction industry.

In the exploration, microplastics tumbling from the air were caught by a pipe and container in a wooden box on a roof at the focal city college grounds. A similar set-up was in a private nursery in Remuera. Practically all of the microplastics were too small to be seen by the unaided eye. Researchers recognized the smallest particles by applying a hued color that produced light under specific circumstances. The mass was dissected using intensity therapy.

“The more modest the size ranges we checked out, the more microplastics we saw,” Rindelaub says. “This is eminent on the grounds that the smallest sizes are the most toxicologically pertinent.”

Nanoplastics, the smallest particles, might possibly enter cells, cross the blood-mind boundary, and develop in organs, for example, the balls, liver, and cerebrum, the paper says.

“Microplastics have also been identified in human lungs and in the lung tissue of disease patients, demonstrating that the inward breath of air microplastics is an openness risk to people,” the paper states.Plastics have also been discovered in the placenta.The paper, co-written by teacher Kim Dirks, Dr. Patricia Cabedo Sanz, and academic partner Gordon Miskelly, called for the normalization of revealing measurements so investigations of airborne microplastics could be better analyzed.

According to the paper’s presentation, “Throughout recent years, 8.3 billion metric tons of plastic have been created worldwide.” Just nine percent have been reused, with the rest either burned or delivered into the climate.

Strands scattered by washing engineered garments, parts shed via vehicle tires and washed by downpour into the sea, and jugs drifting down streams are only a portion of the manners in which plastic is added to the climate. Enduring and maturing separates plastic into ever more modest particles.

The trial was done over nine weeks in September, October, and November of 2020.

More information: Wenxia Fan et al, Evidence and Mass Quantification of Atmospheric Microplastics in a Coastal New Zealand City, Environmental Science & Technology (2022). DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.2c05850

Journal information: Environmental Science & Technology