An example recovered from a cabinet in London’s Regular History Exhibition hall has shown that cutting-edge reptiles began in the Late Triassic, not the Middle Jurassic, as previously thought.

This fossilized relative of living reptiles, for example, screen reptiles, gila beasts, and slow worms, was recognized in a put-away exhibition hall assortment from the 1950s, remembering examples from a quarry close to Tortworth in Gloucestershire, south-west Britain. The innovation didn’t exist then to uncover its contemporary elements.

As a new type of reptile, the new fossil influences all assessments of the origin of reptiles and snakes, collectively known as the Squamata, and influences hypotheses about their rates of development and, surprisingly, is the critical trigger for the gathering’s beginning.

“I originally discovered the specimen in a cabinet full of fossilized Clevosaurus bones in the Natural History Museum’s London storerooms, where I work as a Scientific Associate. This fossilized reptile was rather abundant and was related to the New Zealand tuatara, the only surviving member of the Rhynchocephalia, a group that diverged from the squamates around 240 million years ago.”

Dr. Whiteside

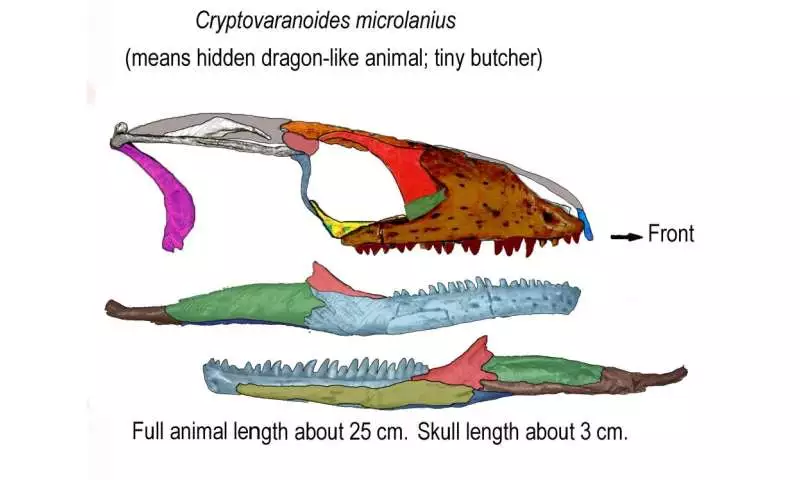

The team, led by Dr. David Whiteside of Bristol’s School of Studies of the Planet, has named their incredible discovery Cryptovaranoides microlanius, which means “little butcher,” in recognition of jaws loaded with sharp-edged cutting teeth.

Dr. Whiteside made sense of it: “I previously recognized the example in a pantry brimming with Clevosaurus fossils in the storerooms of the Normal History Historical Center in London, where I’m a logical partner.” This was a fairly typical fossil reptile, a direct relative of the New Zealand tuatara, the main conqueror of the Rhynchocephalia, which split from the squamates a long time ago.

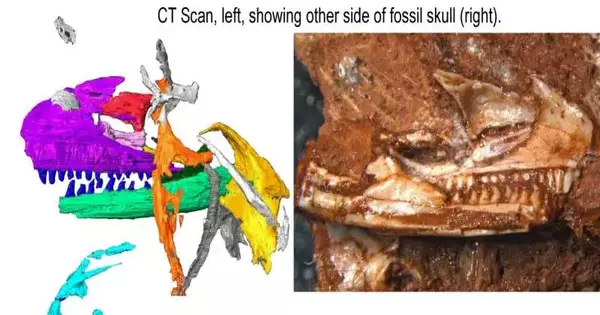

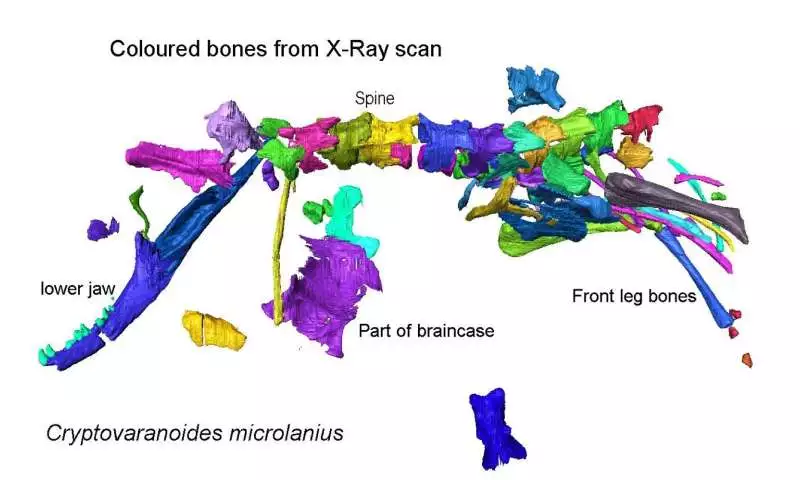

The entire example of a fossil, showing the skull (left) and skeleton (base of the example).David Whiteside, Sophie Chambi-Trowell, Mike Benton, and the Regular History Historical Center UK contributed to this work.

“Our example was basically named “Clevosaurus and another reptile.” As we continued to investigate the case, we became increasingly convinced that it was more closely related to modern reptiles than the Tuatara group.

“We made X-beam outputs of the fossils at the college, and this empowered us to remake the fossil in three aspects and to see every one of the minuscule bones that were concealed inside the stone.”

Cryptovaranoides is clearly a squamate because it differs from Rhynchocephalia in the braincase, neck vertebrae, shoulder region, sight of a middle upper tooth toward the front of the mouth, how the teeth are set on a rack in the jaws (rather than combined to the peak of the jaws), and skull engineering, such as the absence of a lower transient bar.

There is just a single significant crude component not found in current squamates: an opening on one side of the finish of the upper arm bone, the humerus, where a vein and nerve go through. Cryptovaranoides has a few other, clearly crude characteristics, like a couple of columns of teeth on the bones of the top of the mouth; however, specialists have noticed something similar in the living European glass reptile and many snakes; for example, boas and pythons have various lines of huge teeth in a similar region. Notwithstanding this, it is developed like most living reptiles in its braincase, and the bone associations in the skull recommend that it was adaptable.

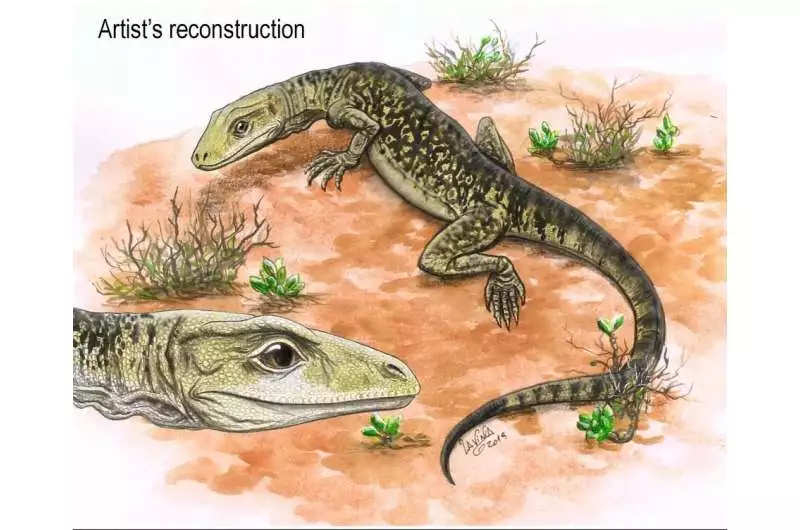

Craftsman’s impression of Cryptovaranoides when it was alive.

“In terms of significance, our fossil moves the origin and spread of squamates back from the Center Jurassic to the Late Triassic,” says co-creator Teacher Mike Benton. “This was a period of major rebuilding of biological systems ashore, with the beginnings of new plant gatherings, particularly present-day type conifers, as well as new sorts of bugs and a portion of the first of the current gatherings like turtles, crocodilians, dinosaurs, and warm-blooded creatures.

“Adding the most established present-day squamates then finishes the image.” It appears that these new plants and creatures appeared as part of a significant change in life on Earth following the end-Permian mass extinction a long time ago, particularly the Carnian Pluvial Episode, a long time ago when environments vacillated between wet and dry and created extraordinary irritation life.

Ph.D. research understudy Sofia Chambi-Trowell remarked, “The name of the new creature, Cryptovaranoides microlanius, mirrors the secret idea of the monster in a cabinet yet, in addition, in its reasonable way of life, living in breaks in the limestone on little islands that existed around Bristol at that point. The species name, signifying “little butcher,” alludes to jaws loaded up with sharp-edged cutting teeth, and it would have gone after arthropods and little vertebrates.

Dr. Whiteside finished up, saying, “This is an extremely extraordinary fossil and liable to become quite possibly one of the main ones tracked down over the most recent couple of decades.” The Normal History Exhibition Hall in London is fortunate in this situation because it is housed in a public collection. We should thank the late Pamela L. Robinson, who recovered the fossils from the quarry and did a lot of preparation work on the sort example and related bones. It was such a pity she didn’t approach CT to examine innovation to assist her with seeing all the details of the example.

More information: David Whiteside et al, A Triassic crown clade squamate, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.abq8274. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abq8274

Journal information: Science Advances