Thecodontosaurus is a herbivorous basal sauropodomorph dinosaur genus that lived in the late Triassic period (Rhaetian age). Its skeletons are mostly known from Triassic “fissure fillings” in South England. Thecodontosaurus was a small bipedal animal that measured about 2 m (6.5 ft) in length. It was one of the first dinosaurs discovered and one of the oldest that ever lived. Many species have been named in the genus, but only Thecodontosaurus antiquus is considered valid today.

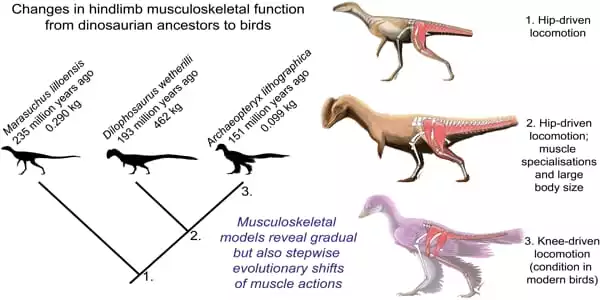

Thecodontosaurus was one of the first dinosaurs to evolve (around 205 million years ago), and it was also one of the first dinosaurs to be discovered and formally described by scientists. Despite its long history, the small, bipedal dinosaur continues to be the subject of exciting new research. A new study led by the University of Bristol has revealed how giant 50-tonne sauropod dinosaurs such as Diplodocus evolved from much smaller ancestors such as the wolf-sized Thecodontosaurus.

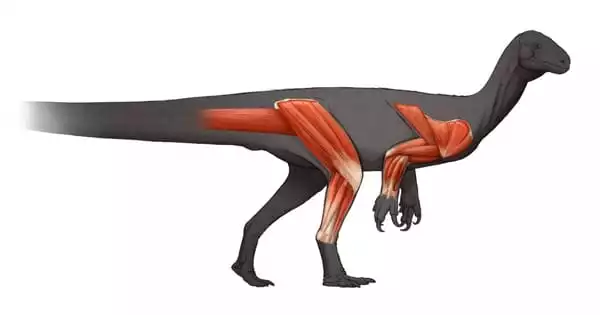

Researchers present a reconstruction of Thecodontosaurus limb muscles in a new study published in the journal Royal Society Open Science, detailing the anatomy of the most important muscles involved in movement.

Thecodontosaurus was a small to medium-sized two-legged dinosaur that lived during the Triassic period in what is now the United Kingdom (around 205 million years ago). Although this dinosaur was one of the first to be discovered and named by scientists in 1836, it continues to surprise scientists with new information about how the earliest dinosaurs lived and evolved.

These kinds of muscular reconstructions are critical for understanding functional aspects of extinct organisms’ lives. We can use this information to use computational tools to simulate how these animals walked and ran.

Professor Emily Rayfield

Antonio Ballell, a PhD student in Bristol’s School of Earth Sciences and the study’s lead author, stated: “The University of Bristol has a large collection of beautifully preserved Thecodontosaurus fossils discovered in the Bristol area. The amazing thing about these fossilized bones is that many of them still have scars and rugosities from the limb musculature’s attachment.”

These characteristics are extremely useful in scientific terms for determining the shape and direction of the limb muscles. Reconstructing muscles in extinct species necessitates not only exceptional fossil preservation, but also a thorough understanding of the muscle anatomy of living, closely related species.

Antonio Ballell also stated: “In the case of dinosaurs, we must consider modern crocodilians and birds, which form a group known as archosaurs, which means “ruling reptiles.” Dinosaurs are extinct members of this lineage, and because of their evolutionary similarities, we can compare the muscle anatomy of crocodiles and birds and study the scars they leave on bones to identify and reconstruct the position of those muscles in dinosaurs.”

Professor Emily Rayfield, the study’s co-author, stated: “These kinds of muscular reconstructions are critical for understanding functional aspects of extinct organisms’ lives. We can use this information to use computational tools to simulate how these animals walked and ran.”

The authors argue that Thecodontosaurus was quite agile and probably used its forelimbs to grasp objects rather than walking based on the size and orientation of its limb muscles. This is in contrast to its later relatives, the giant sauropods, which achieved their enormous body sizes in part by shifting to a quadrupedal posture. Thecodontosaurus’ muscular anatomy appears to indicate that key features of later sauropod-line dinosaurs had already evolved in this early species.

Another co-author, Professor Mike Benton, stated, “From an evolutionary standpoint, our study adds more pieces to the puzzle of how locomotion and posture changed during the evolution of dinosaurs and in the line to the giant sauropods. How did limb muscles change as multi-ton quadrupeds evolved from tiny bipeds? The reconstruction of Thecodontosaurus limb muscles provides new information about the early stages of that important evolutionary transition.”

Thecodontosaurus was discovered to be entirely bipedal. The muscle attachments in its fore and hindlimbs indicate that it was an extremely fast bipedal runner who relied on its weaker front limbs to grasp vegetation, cut it up, and feed it into its mouth. Its advanced running abilities indicate that it was well adapted for high-speed sprinting, most likely to escape predators.