Researchers at the U.S. Department of Energy’s (DOE) Brookhaven Public Lab have fostered a better approach to directing the self-gathering of an extensive variety of novel nanoscale structures involving basic polymers as beginning materials. These nanometer-scale structures appear to be small Lego building blocks under the electron magnifying lens, including railings for miniature archaic palaces and Roman water systems.Yet rather than building whimsical little fiefdoms, the researchers are investigating what these clever shapes could mean for a material’s capabilities.

The group from Brookhaven Lab’s Center for Useful Nanomaterials (CFN) describes their clever way to deal with controlled self-gathering in a paper just distributed in Nature Correspondences. A primer’s examination shows that various shapes have decisively unique electrical conductivity. The work could assist in guiding the plan for custom surface coatings with customized optical, electronic, and mechanical properties for use in sensors, batteries, and channels, and that’s just the beginning.

“This work paves the way for many potential applications and opens doors for researchers from the scholarly world and industry to cooperate with specialists at CFN,” said Kevin Yager, head of the task and CFN’s Electronic Nanomaterials bunch. Researchers keen on concentrating on optical coatings, anodes for batteries, or sun-based cell plans could let us know what properties they need, and we can choose the perfect design from our library of colorful molded materials to address their issues.

Programmed gathering

To make the colorful materials, the group depended on two areas of longstanding skill at CFN. First is the self-gathering of materials called block copolymers, including what different types of handling mean for the association and revamping of these atoms. The second method is called penetration blend, and it involves replacing modified polymer particles with metals or other materials to make the shapes useful and easy to imagine in three dimensions using a checking electron magnifying lens.

“Self-gathering is a truly lovely method for making structures,” Yager said. “You plan the atoms, and the particles suddenly arrange into the ideal design.”

In its most basic form, the cycle begins by depositing thin films of long chainlike particles known as block copolymers onto a substrate.The two closures of these block copolymers are artificially particular and need to be isolated from one another, similar to oil and water. At the point when you heat these molecules through a cycle called tempering, the copolymer’s two closures revamp to become as far apart as is conceivable while still being associated. This unrestricted chain redesign creates a new design with two artificially distinct areas.

Researchers then mix one of the spaces with a metal or other substance to make a copy of its shape and totally consume it with extreme heat. The outcome: a molded piece of metal or oxide with aspects estimating simple billionths of a meter that could be helpful for semiconductors or sensors.

“It’s a strong and versatile method.” “You can undoubtedly cover huge regions with these materials,” Yager said. “Yet, the burden is that this cycle will in general frame just basic shapes—level sheetlike layers called lamellae or nanoscale chambers.”

Researchers have attempted various systems to go beyond those basic plans. Some have tried different things with additional intricate fanning polymers. Others have utilized microfabrication strategies to make a substrate with small posts or channels that guide where the polymers can go. Yet, making more intricate materials and the devices and layouts for directing nano-gathering can be both serious and costly.

“What we’re attempting to demonstrate is that there is an alternative where you can still use basic, low-cost starting materials and get truly fascinating, colorful designs,” Yager explained.

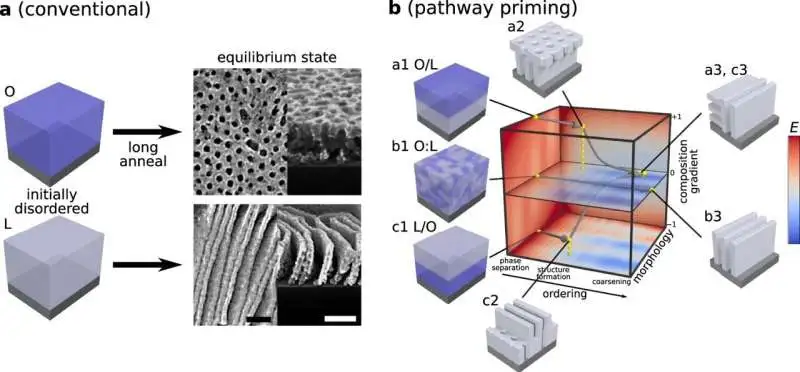

Customary self-gathering versus pathway preparation In customary BCP slim film handling, homogenous films cast from arrangements are strengthened for significant time frames at high temperatures to accomplish regular harmony morphologies (e.g., chambers or lamellae). b Non-minor layered starting setups (a1 and c1) are utilized to start self-gathering pathways that pass through non-harmony transient states (a2 and c2) and progress towards definite morphologies after lengthy tempering times (a3 and c3). These pathways are particular to the related non-layered mix (b1 to b3). Scale bars are 100 nm.

Stacking and extinguishing

The CFN strategy depends on saving block copolymer thin films in layers.

“We take two of the materials that normally are needed to shape altogether different designs and, in a real sense, put them on top of each other,” Yager said. The researchers created more than twelve unique nanoscale structures by varying the request and thickness of the layers, their compound piece, and a variety of other factors, including toughening times and temperatures.

“We found that the two materials would truly prefer not to be defined.” “As they temper, they need to blend,” Yager said. “The blending is making really intriguing new designs and structures.”

On the off chance that tempering is permitted to advance to the end, the layers will ultimately develop to shape a steady design. Yet, by halting the tempering system at different times and cooling the material quickly, extinguishing it, “you can take out transient designs and get a few other intriguing shapes,” Yager said.

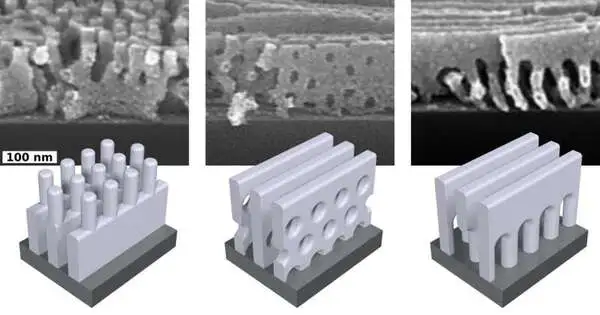

Checking electron magnifying lens pictures uncovered that a few designs, similar to the “railings” and “water systems,” have composite highlights obtained from the request and reconfiguration inclinations of the stacked copolymers. Others have jumble designs or lamellae with an interwoven of openings that differ from the preferred setups of both of the starting materials—or some other self-gathered materials.

Through definite examinations investigating creative mixes of existing materials and exploring their “handling history,” the CFN researchers produced a bunch of plan rules that make sense of and foresee what design will shape under a specific arrangement of conditions. They utilized PC-based sub-atomic element recreations to get a more profound comprehension of how the particles act.

“These recreations let us see where the singular polymer chains are going as they adjust,” Yager said.

Promising applications

Also, obviously, the researchers are pondering the ways that these novel materials may be helpful. A material with openings could fill in as a film for filtration or catalysis; one with railing-like support points on top might actually be a sensor due to its huge surface region and electronic network, Yager proposed.

The main tests, remembered for the Nature Interchanges paper, zeroed in on electrical conductivity. Subsequent to framing a variety of recently molded polymers, the group utilized an invasion blend to supplant one of the recently formed areas with zinc oxide. When they calculated the electrical conductivity of variously shaped zinc oxide nanostructures, they discovered huge differences.

“It’s similar beginning atoms, and we’re changing them all into zinc oxide.” “The main contrast between one and the other is the way they’re privately associated with one another at the nanoscale,” Yager said. “Furthermore, that ends up making an immense contrast in the last material’s electrical properties.” “In a sensor or a cathode for a battery, that sounds vital.”

The researchers are currently investigating the various shapes’ mechanical properties.

“The following edge is multifunctionality,” Yager said. “Since we approach these decent designs, how might we pick one that boosts one property and limits another—or expands both or limits both, assuming that is what we need?”

“With this methodology, we have a ton of control,” Yager said. “We have some control over what the design is (via this newly evolved strategy) as well as what lies beneath the surface for material (via our invasion blend skill).” “We anticipate working with CFN clients on where this approach can lead.”

More information: Sebastian T. Russell et al, Priming self-assembly pathways by stacking block copolymers, Nature Communications (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-022-34729-0

Journal information: Nature Communications