The practices of ancient Native Americans who fished in freshwater have been the subject of research conducted under the direction of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. In the paper, “Freshwater and anadromous fishing in Ice Age Beringia,” distributed in Science Advances, the anthropologists detail zooarchaeological and biomolecular examinations of fish remains from a few archeological destinations in eastern Beringia, a locale of western The Frozen North.

The team looked for fish records at every site that was discovered that was older than 7,000 years. The middle Tanana basin, through which the Tanana River joins the larger Yukon River, was home to ten distinct locations. Eight locales had materials accessible for study, with seven dating from the more youthful Dryas (11,650 to 12,900 years of age).

All 1,110 specimens of fish, all Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes), were identified. Sixty-seven percent of these could be taxonomically identified, with 627 of them Salmon (34%), burbot (58%), whitefish (7%), and northern pike (1%) were among the identified fish.

In the Tanana and the northern part of North America, all of these fish are still caught today. Despite the presence of these fish in the river at the moment, the authors observe a lack of grayling, char, and longnose suckers. Also fascinating is the fact that all known fish existed in freshwater before 11,800 years ago. This suggests that the Younger Dryas event was connected to changes in the environment and climate.

The Younger Dryas is an extinction event caused by climate change. The planet was departing a delayed ice age, mainland icy masses were retreating, and people and megafauna were venturing into new regions. Then, all of a sudden, a climatic shift brought the Northern Hemisphere’s temperatures back into an ice age.

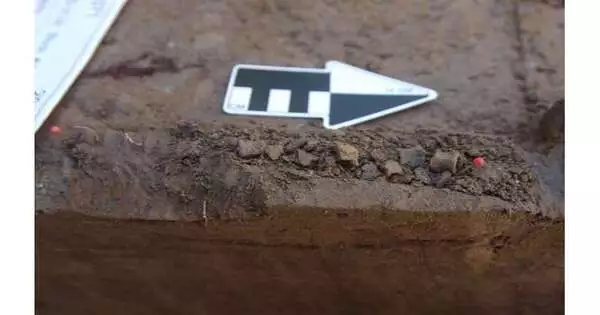

Mead excavation. Credit: Ben Potter

The majority of America’s large mammals had vanished by the time it was over. The wooly mammoth, camels, horses, saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, and short-faced bears all went extinct. Millions of bison, deer, caribou, and moose populations, all of which were frequently targeted by extinct megafauna predators, also saw significant declines.

There were far too many large animals that vanished too quickly across the North American continent for humans to be to blame. The most technologically advanced big game hunters on the planet, the Clovis culture, largely gave up using big game hunting tools at this time.

The power of fishing in the Tanana Waterway Bowl appears during the more youthful Dryas, and afterward, as fast as it shows up, it lessens. The evidence in the study suggests that the switch to fishing was in response to the disappearance of big game from the landscape, demonstrating the adaptability of humans to the environment. Even though the practice of fishing eventually becomes an essential part of native subsistence,

USR excavation. Credit: Ben Potter

The current study suggests that during the Younger Dryas period, Beringians became increasingly dependent on fishing.

The mystery surrounding brown bears—another Younger Dryas survivor—is left out of the study. Brown bears survived despite the extinction of numerous large predatory mammals, including the massive short-faced bear, which is known to hunt large prey. These bears, like humans, were better at fishing and more adaptable eaters. This may be the most important aspect of this study.

More information: Ben A. Potter et al, Freshwater and anadromous fishing in Ice Age Beringia, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adg6802