According to a recent study by scientists from Stanford University and colleagues, published April 6 in Nature Sustainability, the traditional conservation paradigm of “leaving nature alone” can be unreal and unhelpful, especially in a time of increasingly rapid ecosystem change. The study makes the case that a greater understanding of the advantages of good land stewardship is essential for maintaining the health of ecosystems both inside and outside of conserved landscape parcels.

The Santa Cruz Mountains, a region that is home to a wealth of biodiversity and has experienced significant human disturbance, were used by the researchers to illustrate their points. Together with the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network, the team created a digital mapping tool and a socio-ecological health assessment with a focus on this region. The network consists of 24 land stewardship organizations, such as NGOs, state and county parks, a federal land agency, timber companies, an Indigenous tribe, and the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve at Stanford University’s school of humanities and sciences.

With the help of the resulting Sustainable Landscape Health Assessment project, stewardship and conservation activities can be planned and coordinated by identifying the social and ecological indicators of the area in a single geospatial resource.

“To maintain the Santa Cruz Mountains ecosystem’s health and benefit the local population, we wanted a way to visualize and understand the current state of the ecosystem,”

Study author Anthony D. Barnosky, now professor emeritus at the University of California Berkeley

“We wanted a way to visualize and understand the current state of the Santa Cruz Mountains ecosystem to keep it healthy and serve the people of the region,” said study author Anthony D. Barnosky, who is now a professor emeritus at the University of California, Berkeley, and was involved in this study while executive director of the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve. A socio-ecological health model and assessment for use by Network members were developed by Jasper Ridge because it was a university partner and a founding member of the Network. This project combined academic research with a crucially needed practical application.

Nicole E., the study’s principal author, spoke with Stanford News about the investigation. Heller is a doctor. D. Kelly McManus Chauvin, a research scientist at the Hadly Lab, who assisted in project leadership while she was a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford’s Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve during this project; Dylan Skybrook, the principal investigator at the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network; and Barnosky, 05, a former director of conservation science at the Peninsula Open Space Trust and currently an associate curator at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

This map is an approximate visualization of the diverse open space land management entities around and within the Santa Cruz Mountains. Properties related to members of the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network are outlined in blue. Credit: Heller et al, Nature Sustainability (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-023-01096-7

What exactly do you mean by “stewardship” of the environment?

Skybrook: The term “stewardship” is sometimes used to refer to the purchase of land and significant restoration initiatives. However, we also use it to refer to the ongoing upkeep required to maintain the health of ecosystems.

That stewardship might not be visible to the general public. For instance, hikers in state parks frequently aren’t aware of the enormous amount of work that went into purchasing the land, planning the trails and parking areas, developing interpretive signage, or clearing the land before it was turned into a park. With the removal of invasive species, controlled fires, creek restoration for fish passage, and other measures, land needs to be managed continuously.

How is maintaining landscapes under conservation better than letting nature run its course?

Heller: According to the “leave nature alone” paradigm, conservation science has a bias toward viewing nature as distinct from humans. Although we can enclose a plot of land to keep it out of development, that doesn’t guarantee that the species and habitats there will be protected. They are still susceptible to invasive species, climate change, and other stresses in the larger landscape. In order to manage stresses and boost ecosystem resilience, stewardship is crucial both inside and outside of conservation sites.

Barnosky: Our increasing population, use of natural resources, alteration of the climate, and alteration of ecosystems have all changed the way the planet functions. The environments that some species have called home for millennia have changed so quickly that they are unable to adapt. Therefore, species must move or perish. Stewardship is necessary for that movement; if the corridors don’t exist, we’ll have to transport species ourselves.

Why is ecosystem stewardship underfunded and understudied?

Heller: “Bucks for acres” has traditionally been the focus of the land conservation community. It happens frequently that land is bought and protected, but active management—which may be necessary to maintain their unique values—has not been a funding priority. This circumstance is shifting. Conservation land trusts and other organizations are developing stewardship plans and endowments as part of conservation, and these groups are increasingly realizing that in order to meet the diverse needs of the community, conservationists must collaborate closely with land stewards.

McManus Chauvin: Many of the organizations we collaborate with are accustomed to receiving media attention. Even if no damage is caused, it is always a local news story if a prescribed burn crosses a fire line, for example. As a result, land managers are now cautious about how their actions might be perceived and reluctant to share information that might be interpreted differently than they intended. We have taken great care to make sure that all of our decisions about what to include and what to share are made with the network’s full support, which has contributed to building trust. Another issue is the fact that many of these data are not centralized or collected consistently across numerous organizations.

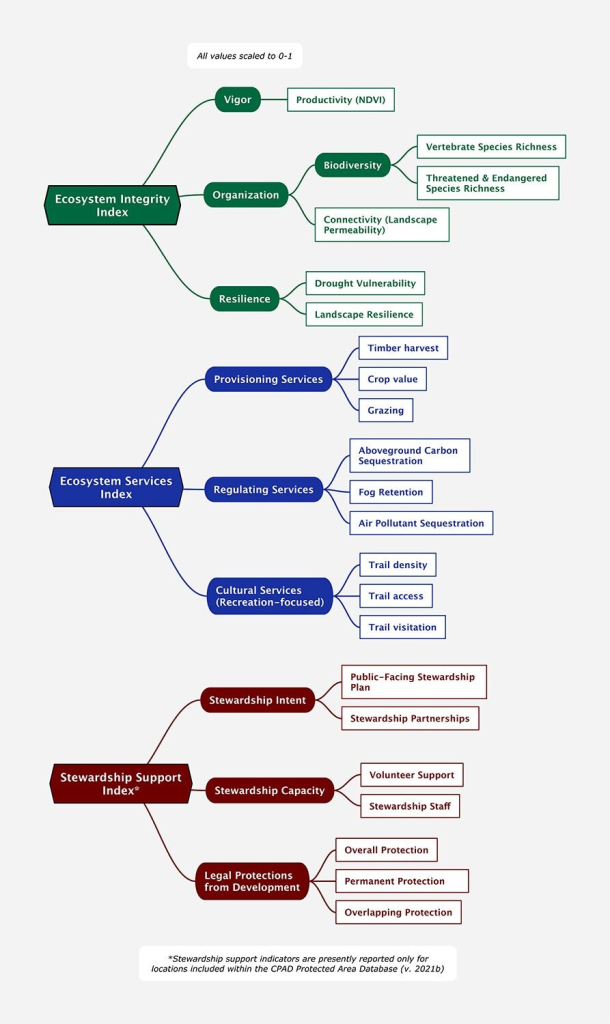

A figure outlining the metrics included in the Sustainable Landscape Health Assessment Framework. This framework was determined through scientific review, data collection, expert consultations, and collaboration between network members. Credit: Heller et al, Nature Sustainability (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-023-01096-7

Instead of a traditional ecosystem health study, a socio-ecological health assessment of the network was developed. Why?

Heller: Ecological health frameworks frequently center on monitoring biophysical indicators, which are components of the system that we might want to keep in abundance, like the status of particular wildlife, plant species, and habitat types. Given how crucial stewardship is to the health of the land, our framework not only incorporates biophysical indicators but also a human support lens.

McManus Chauvin: Analyses of the health of ecosystems have rarely taken into account human input. To view the network’s topographies, we selected three lenses. In frameworks for health assessment, the first two lenses—ecosystem integrity and ecosystem services—are well established. With our third strategy, stewardship support, we hope to integrate human services into the discussion of health.

In order to understand people as ecological actors through land stewardship and investigate how those ecological interactions scale up to local and regional effects, we are calling for collaborative research with social scientists. More interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary perspectives must be incorporated into conservation science to make it more social-ecological.

The SLHA will be put to what use?

Skybrook: One of the goals of the Santa Cruz Mountains Stewardship Network is to assist member organizations in considering stewardship at a landscape or regional scale as opposed to just the individual properties each organization is in charge of. For land managers to have a wider context for their decisions, data at that systemic, big-picture scale is now provided by the digital mapping resource and the SLHA.

On the east side of the Santa Cruz Mountains, Jasper Ridge is one of the few ecosystems that is protected, according to Barnosky. The most significant “laboratory” that Stanford has is Jasper Ridge. It helps us understand nature, care for it in these rapidly changing times, and maintain nature’s vitality for future generations. The SLHA, and hopefully more work like it, can be helpful in helping us understand how to properly manage nature and what our long-term stewardship effects will be on ecosystems.

More information: Nicole E. Heller et al, Including stewardship in ecosystem health assessment, Nature Sustainability (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-023-01096-7