The bugs are astounding. They’re valuable in any event, even when they’re dead.

Rice University mechanical designers are telling us the best way to reuse expired bugs as mechanical grippers that can mix into regular habitats while getting objects, as different bugs, that offset them.

Why?

“It is the situation that the insect, after it’s departed, is the ideal engineering for limited scope, normally inferred grippers,” said Daniel Preston of Rice’s George R. Earthy School of Engineering.

An open-access concentrate on in Advanced Science frames the cycle by which Preston and lead creator Faye Yap saddled a bug’s physiology in an initial move toward a clever area of exploration they call “necrobotics.”

Preston’s lab has some expertise in delicate mechanical frameworks that frequently utilize contemporary materials rather than hard plastics, metals, and gadgets. “We utilize a wide range of intriguing new materials like hydrogels and elastomers that can be incited by things like synthetic responses, pneumatics, and light,” he said. “We even have some new work on materials and wearables.

“This area of delicate mechanical technology is loads of fun since we get to utilize previously undiscovered kinds of activation and materials,” Preston said. “The bug falls into this line of request.” Something hasn’t been utilized previously, but has a ton of potential. “

Dissimilar to individuals and different warm-blooded animals that move their appendages by synchronizing restricting muscles, bugs use power through pressure. A chamber close to their heads agrees to send blood to their appendages, constraining them to enlarge. At the point when the strain is feeling quite a bit better, the legs contract.

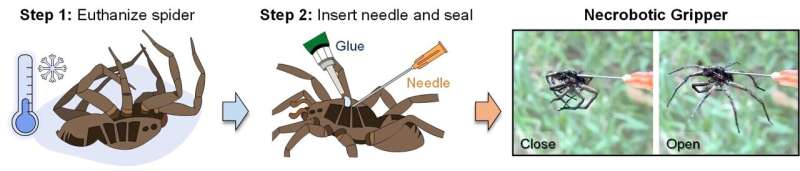

A delineation shows the interaction by which Rice University mechanical specialists transform expired insects into necrobotic grippers, ready to get a handle on things when set off by water pressure.

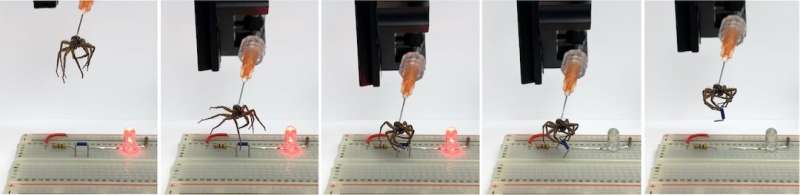

The corpses Preston’s lab squeezed into administration were wolf bugs, and testing showed they were dependably ready to lift over 130% of their own body weight, and once in a while, significantly more. They had the grippers control a circuit board, move items, and even lift another bug.

The specialists noted that more modest bugs can convey heavier burdens in contrast with their size. On the other hand, the bigger the bug, the more modest the heap it can convey in contrast with its own body weight. Future exploration will probably include testing this idea with bugs other than the wolf bug, Preston said.

Gab said the undertaking started not long after Preston laid out his lab in Rice’s Department of Mechanical Engineering in 2019.

“We were moving things around in the lab when we noticed a nestled in at the edge of the corridor,” she explained.”We were truly inquisitive with regards to why insects twist up after they kick the bucket.”

Rice graduate understudy Faye Yap with a departed wolf bug. Gab joins the insects to a needle and feeds air into their appendages to go about as a necrobotic gripper.

A fast hunt tracked down the response: “Bugs don’t have hostile muscle matches, similar to biceps and rear arm muscles in people,” Yap said. “They just have flexor muscles, which permit their legs to twist in, and they expand them outward by water-driven pressure.” At the point when they pass on, they lose the capacity to compress their bodies effectively. That is the reason they twist up.

Credit: Preston Innovation Laboratory

At that point, we were thinking, “Gracious, this is really fascinating.” We needed to figure out how to use this instrument,” she said.

Interior valves in the bugs’ water-driven chamber, or prosoma, permit them to control every leg exclusively, and that will likewise be the subject of future examination, Preston said. “The dead insect isn’t controlling these valves,” he said. They’re all open. That helped us out in this review since it permitted us to control every one of the legs simultaneously. “

Setting up a bug gripper was genuinely basic. Gab took advantage of the prosoma chamber with a needle, joining it with a spot of superglue. The opposite end of the needle was associated with one of the lab’s test rigs or a handheld needle, which conveyed a brief measure of air to initiate the legs quickly.

A delineation shows the cycle by which Rice University mechanical designers transform expired bugs into necrobotic grippers, ready to get a handle on things when set off by water-driven pressure. Preston Innovation Laboratory is to blame.

The lab ran one ex-bug through 1,000 open-close cycles to perceive how well its appendages held up, and viewed it as genuinely vigorous. “It begins to encounter a few miles as we draw near to 1,000 cycles,” Preston said. “We imagine that is connected with issues with parchedness of the joints.” We want to beat that by applying polymeric coatings.

What diverts the lab’s work from a cool trick into a helpful innovation?

Preston said a couple of necrobotic applications have seemed obvious to him. “There are a ton of pick-and-spot errands we could investigate, tedious undertakings like arranging or moving items around in these little scopes, and perhaps things like the gathering of microelectronics,” he said.

“Another application could be sending it to catch more modest bugs in nature since it’s intrinsically disguised,” Yap added.

A gripper is utilized to lift a jumper and break a circuit on an electronic breadboard, switching off an LED. Preston Innovation Laboratory is to blame.

“Likewise, the actual bugs are biodegradable,” Preston said. “So we’re not presenting a major waste stream, which can be an issue with additional customary parts.”

Preston and Yap know the analyses might sound to certain individuals like the stuff of bad dreams, yet they get out that whatever they’re doing doesn’t qualify as restoration.

“Regardless of it seeming as though it could have reawakened,” Preston said. “We’re sure that it’s lifeless, and we’re involving it in this situation rigorously as a material derived from a once-living insect.” “It’s giving us something truly helpful.”

More information: Te Faye Yap et al, Necrobotics: Biotic Materials as Ready‐to‐Use Actuators, Advanced Science (2022). DOI: 10.1002/advs.202201174

Journal information: Advanced Science