A group of researchers utilizing enormous information and a recreation-based model to examine virtual entertainment “tweets” around the 2020 official political race tracked down that the spread of electoral cheating paranoid fears on Twitter (presently called X) was helped by a pessimism predisposition. Driven by Bricklayer Youngblood, Ph.D., a post-doctoral individual in the Establishment for Cutting Edge Computational Science at Stony Creek College, the discoveries are distributed in Humanities and Sociologies Correspondences.

The scientists recreated the behavior of around 350,000 genuine Twitter clients. They observed that the sharing examples of approximately 4 million tweets about electoral misrepresentation are reliable, with individuals being significantly more likely to retweet social posts that contain a more grounded, gloomy inclination.

“Our findings suggest that the spread of voter fraud messages on Twitter was driven by a bias for tweets with more negative emotion, which has important implications for current debates about how to combat the spread of conspiracy theories and misinformation on social media.”

Mason Youngblood, Ph.D.,

The information for their review came from the VoterFraud2020 dataset, gathered between October 23 and December 16, 2020. This dataset incorporates 7.6 million tweets and 25.6 million retweets that were gathered continuously utilizing X’s streaming application program point of interaction under the laid-out rules for moral and web-based entertainment information use.

“Paranoid notions about huge-scope electoral misrepresentation spread broadly and quickly on Twitter during the 2020 U.S. official political race, yet its hazy cycles are answerable for their enhancement,” says Youngblood.

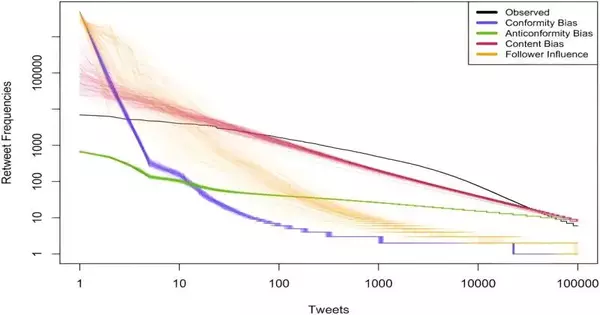

Considering that, the group ran reenactments of individual clients tweeting and retweeting each other under various levels and types of mental predisposition and contrasted the result with genuine examples of retweet conduct among advocates of electoral cheating paranoid notions during and around the political decision.

“Our outcomes propose that the spread of electoral cheating messages on Twitter was driven by an inclination for tweets with a more pessimistic inclination, and this has significant ramifications for current discussions on the most proficient method to counter the spread of paranoid fears and deception via web-based entertainment,” Youngblood adds.

Through their reenactments and mathematical examination, Youngblood and partners observed that their outcomes are consistent with past exploration by others proposing that sincerely regrettable substances enjoy a benefit via virtual entertainment across various spaces, including news inclusion and political talk.

The model additionally showed that despite the fact that pessimistic tweets were bound to be retweeted, quote tweets would in general be more moderate than the first ones, as individuals tended not to enhance antagonism while remarking on something.

Youngblood says that, on the grounds that the group’s reenactment-based model reproduces the examples in the genuine information very well, it might possibly be helpful for mimicking mediations against falsehood later on. For instance, the model could be effortlessly changed to mirror the manners in which online entertainment organizations or strategy producers could attempt to control the spread of data, for example, by lessening the rate at which tweets hit individuals’ timetables.

More information: Mason Youngblood et al, Negativity bias in the spread of voter fraud conspiracy theory tweets during the 2020 US election, Humanities and Social Sciences Communications (2023). DOI: 10.1057/s41599-023-02106-x