We presently know about the eating regimen of an ancient animal that grew up to over two meters in length and lived in Australian waters during the age of the dinosaurs because of the force of X-beams and a group of researchers at the Australian National University (ANU) and the Australian Historical Center Exploration Foundation (AMRI).

Micro-CT scans were used to look inside the fossilized stomach of a small marine reptile, a plesiosaur named “Eric” after a song by the comedy group Monty Python, to find out what the animal ate before dying.

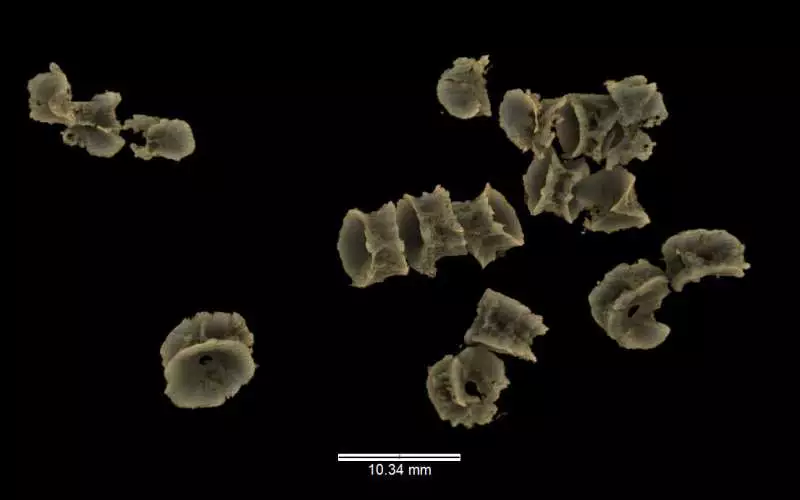

In support of previous research from 2006, the researchers were able to locate 17 fish vertebrae in Eric’s gut that had not been previously described. This confirmed that the plesiosaur primarily ate fish.

“We used very strong X-rays in our study to observe the animal’s stomach contents in unprecedented detail, and we discovered fish bones in its gut.”

Ph.D. researcher Joshua White, from the ANU Research School of Physics and the AMRI,

The findings have the potential to assist scientists in gaining a deeper understanding of the evolutionary history of extinct organisms like Eric and in making predictions regarding the nature of our marine life’s potential future. The study, according to the researchers, demonstrates the feasibility of reconstructing the diets of other extinct organisms that once inhabited Earth hundreds of millions of years ago with the help of X-rays.

Ph.D. researcher Joshua White from the AMRI and ANU Research School of Physics stated, “Previous studies examined the exterior surface of Eric’s opalized skeleton to find clues.”

“However, due to the fact that fossilized stomach contents are uncommon and there may be more hidden beneath the surface that paleontologists would be nearly unable to see without destroying the fossil, this approach can be challenging and limited.”

“We accept our review as the principal in Australia to utilize X-beams to concentrate on the stomach items in an ancient marine reptile.”

“We were able to see the animal’s stomach contents in unprecedented detail with the assistance of extremely powerful X-rays, including the discovery of fish bones in its gut.”

“When dealing with valuable and delicate specimens like Eric,” “the benefit of using X-rays to study these prehistoric animals is that it does not damage the fossil.”

A miniature CT filter showing proof of fish bones inside Eric the plesiosaur’s stomach Credit: To distinguish between what he believed to be evidence of fish bones, gastroliths, also known as stomach stones, and other materials that the reptile had consumed, Joshua White/ANU White sifted through mountains of data and CT imagery. A three-dimensional model of Eric’s gut contents was created using the data. Credit: Joshua White/ANU.

According to White, Eric “was a mid-tier predator, sort of like a sea lion equivalent, that ate small fish and probably was preyed upon by larger, apex predators.”

“Eric is one of Australia’s most complete opalized vertebrae skeletons, so we are fortunate in that regard as well.” The fossil is nearly 93% complete, which is unprecedented in any fossil record.

“Opalized vertebrae fossils can only be found in Australia, and that’s about the only place.”

According to the researchers at the ANU, gaining a deeper understanding of the diet of extinct organisms is an essential step in comprehending their evolutionary history. However, this knowledge can also assist us in comprehending how climate change might affect animals that are still alive today.

According to White, “understanding these changes can help predict how animals of today will respond to current and emerging climate challenges.” “As environments change, so does a marine reptile’s diet.”

“In the event that there’s any change to a creature’s eating routine, we need to take a gander at why this change happened, and by some action we can contrast this with present-day creatures, for example, dolphins or whales, and attempt to anticipate how their weight control plans could change because of environmental change and why.”

Eric was first found in the opal mines in Coober Pedy, South Australia, in 1987. The Australian Museum in Sydney has the prehistoric predator on display.

Alcheringa has published the study, A Journal of Palaeontology from Australasia.

More information: Joshua M. White et al, Investigating gut contents of the leptocleidian plesiosaur Umoonasaurus demoscyllus using micro-CT imaging, Alcheringa: An Australasian Journal of Palaeontology (2023). DOI: 10.1080/03115518.2023.2194944